MARCH

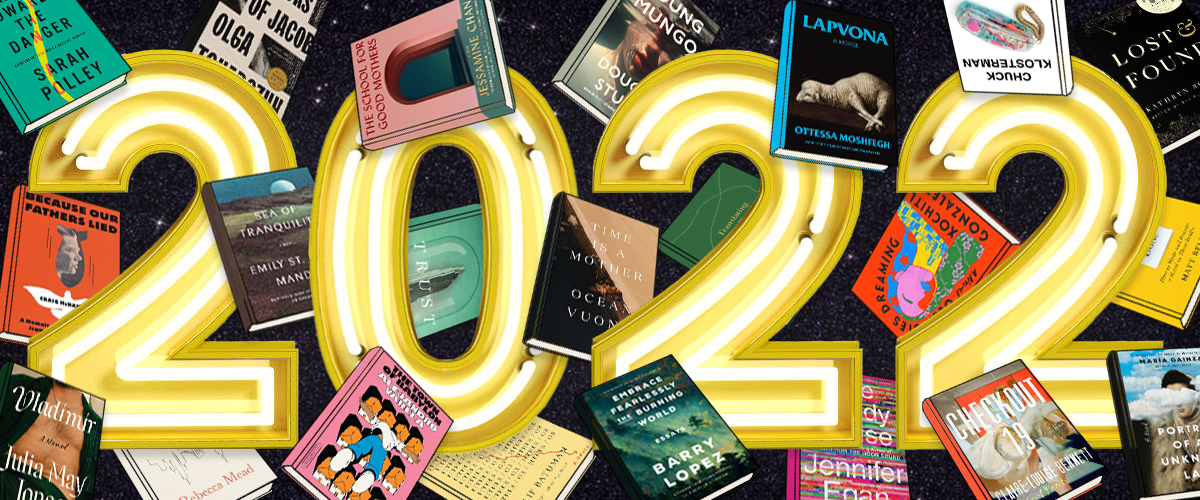

Sarah Krasnostein, The Believer: Encounters with the Beginning, the End, and our Place in the Middle

Tin House, March 1

A fascinating portrait of the human condition, Sarah Krasnostein’s latest explores a range of belief systems through six profiles—of a death doula, a geologist, a ghost-hunting neurobiologist, ufologists, a woman accused of murder, and Mennonite families living in New York. A great read for our “deeply fractured times,” as they say. –ES

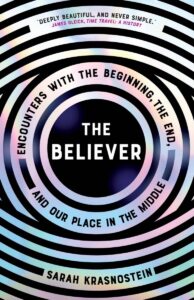

Margaret Atwood, Burning Questions

Doubleday, March 1

What I would give to live inside the mind that brought us The Handmaid’s Tale! Burning Questions offers us a generous, enjoyable glimpse. It takes a special kind of writer to bring such a wide variety of topics under one roof. Here we have: the power of storytelling across cultures, Trump, the pandemic, the climate crisis, zombies—yes, zombies. Many of these topics may be timely, but I’m sure there is sage wisdom in here for the ages. All hail Margaret Atwood! –KY

Missouri Williams, The Doloriad

MCD x FSG Originals, March 1

This book sounds extremely up my alley: lyrical, visceral, depraved, demented, a post-apocalyptic Greek tragedy (read: an incestuous family whose Matriarch dreams of singlehandedly rebooting humanity) run through with VHS tapes and madness. Plus, Mary South compared it to Geek Love! I am sold. –ET

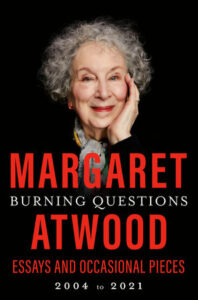

Pankaj Mishra, Run and Hide

FSG, March 1

Pankaj Mishra is an exceedingly elegant systems thinker; his unparalleled intellectual grasp of contemporary political and economic culture is always a delight to encounter. Mishra writes with erudition, clarity, and deep humanity, and doesn’t shy away from satisfyingly targeted polemics that call out shallow thinking in service of power. But apparently he’s also a novelist? Run and Hide is Mishra’s first work of full-length fiction in 20 years, and tells the story of three friends who rise from humble origins—and the vaunted classrooms of the Indian Institute of Technology—to claim a seat at the global tech table, along with all the money, prestige, and jetsetting hubris that comes with it. –JD

Harvey Fierstein, I Was Better Last Night

Knopf, March 1

This memoir by the four-time Tony Award-winning actor and playwright, gay rights activist, and all-round cultural icon (whose inimitable voice was once memorably compared to that of “a deep-throated jazz diva who has just tossed back a double-bourbon”) is sure to be an absolute delight, as well as a fascinating window into the gay rights movement of the 70s and 80s and the New York theater scene of the past four decades. “I never thought I’d spill my guts but, when COVID locked me in with my computer, I figured I’d amuse myself and give this a try,” Fierstein said of I Was Better Last Night. “Well, here is the outrageous, juicy, scary, and mostly true result of my efforts.” Audiobook strongly recommended. –DS

Lee Cole, Groundskeeping

Knopf, March 1

As someone constantly awaiting the next great campus novel, I am already counting the days until debut. Cole’s campus denizens are the classic writer in residence, Alma, and less classically: the groundskeeper, Owen. They are similar in some ways—they both write, and are obsessed with the craft and the story of their lives—but different in almost every other way: class, political upbringing, education. What could go wrong? –JH

Sarah Polley, Run Towards the Danger: Confrontations with a Body of Memory

Penguin Press, March 1

Sarah Polley’s autobiographical documentary, The Stories We Tell, is one of my favorite works of art, in any medium. And now, in an era when we all seem to be revealing ourselves, all the time, via an endless shallow stream of digital ephemera, the depth of Polley’s 2012 cinematic memoir is even more of a revelation. So I am eager to dig into Run Towards the Danger, a collection of six essays that promise to “capture a piece of Polley’s life as she remembers it, while at the same time examining the fallibility of memory, the mutability of reality in the mind, and the possibility of experiencing the past anew, as the person she is now but was not then.” –JD

Warsan Shire, Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head

Random House Trade Paperbacks, March 1

This full-length collection of poetry by Somali British poet Warsan Shire depicts a journey to womanhood intermixed with pop culture and news references. Shire’s body of work has always impressed me with its triumph of visceral, biting imagery. Known for her contributions to Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade and Black Is King, Shire uses language to shape loneliness into wise phantoms and transform heartbreak into blood, muscle, and bone. It’s evident in earlier poems like “The House,” wherein women are sanctuaries under siege and men are brute practitioners of ultraviolence. Shire’s poetry flows with power like the earth splitting wide open. –VW

Claire Louise Bennett, Checkout 19

Riverhead, March 1

This is an easy one: Checkout 19, recently published in the UK, has already seen its fair share of rave reviews. Just as with Bennett’s Pond, don’t expect a linear story, but do expect ramblings, musings, interiority, and the poetry of thought, even on mundanity. Bennett has the superb ability to capture the reality of a mind: it is rare to think in fully formed, conclusion-ridden ideas, after all. Our brains are often a maze, and we find ourselves repeating, circling, ending up somewhere we didn’t mean to go. Checkout 19 is a fresh take on the coming-of-age novel—one in which we don’t already know how the story will end, or if it will have an “ending” at all. Bennett manages to convince the reader that somewhere, her narrator continues to think and ponder and live and wrestle with being in a body, like the rest of us. –JH

Sarah Moss, The Fell

FSG, March 1

If you’ve read Ghost Wall and Summerwater, you know a Sarah Moss book when you see it! There is always the electric touch of danger lacing its fingers through the story. In this particular tale, a woman is confined to her house for a mandatory quarantine. It’s a suffocating situation we can all relate to. So, she sneaks out for a walk. No one has to know! But as the title implies, she slips and falls. There she lies: injured, vulnerable, at the mercy of those around her. It’s the end of the world, seen from a particular angle only the incisive Sarah Moss could show us. And if you’re wondering why you should read another book about the pandemic that you are still living through, it’s because there is a good dose of humor and humanity in these pages, too. –KY

Meghan O’Rourke, The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness

Riverhead, March 1

Megan O’Rourke’s nearly decade-long investigation into chronic illness is part memoir, part journalism, filled with interviews with doctors, patients, researchers, and public health experts. The Invisible Kingdom takes the question of how we treat hard-to-understand medical conditions and argues for a reimagining of how we understand our bodies and our relationship to our health. O’Rourke is a poet above all else, and it’s with incredible, lyrical empathy that she not only shares her own story of and eventual diagnosis with late-stage Lyme disease, but puts it in perspective of an entire generation of patients who’ve been dismissed: “It is a truth universally acknowledged among the chronically ill that a young woman in possession of vague symptoms… will be in search of a doctor who believes she is actually sick.” A must read. –EF

Kathryn Davis, Aurelia, Aurélia

Graywolf, March 1

Kathryn Davis’ first memoir is recognizably hers—place-based, with hints of magical realism, about journeys, movement—but is by necessity much more personal than her fiction. She writes about being a teenager, trying on identities like clothes, and about being in late middle age, resolutely someone, and yet still wondering, still trying on the other clothes, even while liking her own. At the memoir’s center is the death of her husband, and her reflections about the life they lived together. By turns grieving and joyful, the book explores the pivotal crossroads in her life, and takes us along as she continues the journey. –JH

Gu Byeong-Mo, tr. Chi-Young Kim, The Old Woman with the Knife

Hanover Square Press, March 1

A sixty-five-year-old female assassin, need I say more? Byeong-Mo’s novel follows Hornclaw, the aforementioned female assassin who finds herself on the cusp (or rather, the expectation) of retirement. But when an injury leads her to a doctor and his family, her own feelings and emotions come up to the surface, and with them, a new kind of stake. The Old Woman with the Knife, Byeong-Mo’s first novel to be translated into English from Korean, is sardonic and funny, as it probes at the expectations around aging women and their bodies. –SK

Negesti Kaudo, Ripe

Mad Creek, March 2

A debut essay collection from an exciting new voice, Negesti Kaudo’s Ripe probes topics of race, class, sexuality, and more through cultural criticism and her experiences as a young Black woman in the Midwest. It joins the ranks of other recent collections on intersectionality such as Hood Feminism and Against White Feminism, a must-read contemporary canon. –ES

NoViolet Bulawayo, Glory

Viking, March 8

In 2013, NoViolet Bulawayo took the world by storm with her incredible debut, We Need New Names. (It has been argued that that book is actually one of the best debuts of the decade, a sentiment that I wholeheartedly agree with.) Now, the Booker-prize finalist is back. Glory is set in a fictional place, at a familiar time of turmoil. Inspired by the 2017 coup that saw the fall of Zimbabwe’s president, Glory starts with the dethroning of Old Horse, a leader no more. Through the voices of the animal kingdom, we are shown a nation on the precipice. NoViolet Bulawayo has an unmatched ability to enchant the trials and tribulations of life lived in a nation in turmoil. In the past, she has done this through the eyes of the children. In this one, through animals. Like all good allegories, Glory is sure to be an impressive feat of imagination and a haunting reflection of reality. –KY

Matt Bell, Refuse to Be Done

Soho Press, March 8

The subtitle of this one—”How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts”—is about as compelling a pitch as I can imagine. I struggle mightily with revision, so I’m excited to read Bell’s “encouraging and intensely practical” craft book. –JG

Maayan Eitan, Love

Penguin Press, March 8

Maayan Eitan’s debut follows Libby, a young sex worker looking for, yes, love. Through a series of short fragments, Libby tests out different narratives about her life and past. Last year, Love was a “literary sensation in Israel”; let’s see what it does here. –WC

Tara Isabella Burton, The World Cannot Give

Simon & Schuster, March 8

Burton’s second novel is just as deliciously involving as her debut Social Creature, but makes rather better use of her doctorate in theology and ongoing religious scholarship. It is set at a tiny academy in Maine, where a sensitive teenager obsessed with an obscure novel—whose author, a student at the school, died at 19—falls in with a cultish church choir of boys, led by the brutal and neurotic Virginia. It’s a book about the nature of and limits of fervor, religious, sexual, and otherwise, and a spellbinding coming of age story that—despite being set in the Instagram-laden present—feels somehow plucked out of time. –ET

Stewart O’Nan, Ocean State

Grove, March 8

This is a book about murder, but it is not a mystery. Well, there’s mystery, but not in the whodunnit sense. In the first line we are told who died, and who killed them; what expands from that immediate reveal is the slow unraveling of why. The story centers on the killer and her family, her mother, her sister, and all the tangled lives and actions that one by one, add up to the final tragedy. This is a beautiful, devastating novel of family and young love, and unredeemable acts. –JH

Christopher Kempf, Craft Class: The Writing Workshop in American Culture

Johns Hopkins University Press, March 15

As of 2016, there are over 350 creative writing MFA programs in the U.S.; 40 years prior, there were only 52. Nearly all operate on the workshop model. Poet Christopher Kempf places the idea of the artisanal workshop in its capitalist historical context, taking the craft/labor metaphor as its central question: in the “workshop,” what type of work is being done? And what are the contradictions that arise when writing, like other artisanal goods, is evaluated as both labor and not-labor? Worthwhile if you’re a creative writer—or reader. –WC

Melissa Febos, Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

Catapult, March 15

If I could do cartwheels, I would have cartwheeled across the room when I learned that the brilliant Melissa Febos is gifting us with a memoir craft book. One of my all-time favorite writers and thinkers, Febos draws on her own life trajectory to discuss matters of so-called navel-gazing, writing about others, and “the power of divulgence.” I can’t wait to dive in to this one. –ES

Elena Ferrante, tr. Ann Goldstein, In the Margins

Europa Editions, March 15

There is so much mystery shrouding the beloved Italian author, Elena Ferrante. For years, readers and scholars have gone on some deep dives, trying to pinpoint the writer’s identity. If you, too, have wondered who exactly penned My Brilliant Friend, hopefully it comes from a place of deep admiration. The latest book from Elena Ferrante, translated by Anne Goldstein, is sure to answer some of your questions. Who is Elena Ferrante as a reader? As a fellow writer, struggling against the page? Who have been her influences? In the Margins is that rare peek inside the lively mind of one of our most influential writers working today. –KY

Eloghosa Osunde, Vagabonds!: A Novel

Riverhead, March 15

Plimpton Prize winner and consistently thought-provoking Paris Review columnist Eloghosa Osunde’s debut novel catalogues the lives of an ensemble cast of vagabonds, “for whom life itself is a form of resistance,” before bringing them all together for the event of a lifetime. Said Osunde, writing Vagabonds! “relocated [her] to a place where imagination meets courage.” –WC

María Gainza, tr. Thomas Bunstead, Portrait of an Unknown Lady

Catapult, March 22

Gainza’s Optic Nerve was one of my favorite novels of 2019 (when it was first published in English), so I’ve been anxiously awaiting this follow-up. Like Optic Nerve, Portrait of an Unknown Lady is intelligent and tensile, if mostly plotless, taking place in the world of art and those who both appreciate and make it, though here the narrator is not tracing her own life through art, but rather the life of a famous (or infamous) Argentinean counterfeiter, the truth of whom eludes her. She interviews acquaintances, sifts through court records, and even reproduces an auction catalogue; the result is a loose investigation into the nature of art and of memory, scattered with gems of intrigue and insight. –ET

Alejandro Varela, The Town of Babylon

Astra House, March 22

It’s hard to imagine a scene riper for drama and psychological exploration than a twenty-year high school reunion: that’s where we find protagonist Andrés, a professor, in The Town of Babylon, Alejandro Varela’s debut novel. As Andrés reckons with figures from his past, his story also becomes an inquiry into the ways that queerness, race, and class affect the course of one’s life. –CS

Colm Tóibín, Vinegar Hill: Poems

Beacon Hill Press, March 22

Tóibín’s collection of poems rests at the wedge between the private and the public. Whether it be queer love or COVID or religion, whether they move through Dublin or Venice or Enniscorthy, Tóibín situates his poems at an interstice, lacing them with threads of both humor and emotion. Written over the course of many decades, his first poetry collection is an extension of the themes of his novels, explored via the malleability of verse. –SK

Candice Wuehle, Monarch

Soft Skull, March 22

Wuehle has published three poetry collections, and as a sucker for a poet novel, this is a major selling point for me. Her debut novel “merges iconic true crime stories of the ’90s (Lorena Bobbitt, Nicole Brown Simpson, and JonBenét Ramsey) with theories of human consciousness, folklore, and a perennial cultural fixation with dead girls.” Sold. –JG

Amanda Oliver, Overdue: Reckoning with the Public Library

Chicago Review Press, March 22

Part memoir, part ode, part indictment, Overdue is the firsthand story of Amanda Oliver’s life as librarian, starting with her first day on the job as an eager young professional in an underserved neighborhood in Washington, DC. What Oliver slowly discovers is that—despite the fact they do indeed offer hope and opportunity to so many who wouldn’t otherwise have it—libraries nonetheless mirror all of the deep systemic problems contained in American society. How can libraries repair their own institutional fault lines around racism and economic oppression, wonders Oliver. How can libraries survive America? –JD

Maud Newton, Ancestor Trouble

Random House, March 29

In her new memoir, Maud Newton plumbs the depths of the multibillion-dollar industry of ancestral research in an effort to make sense of her own family history, which is peppered with stories both bizarre and traumatic. Newton doesn’t avoid the sins of her kin—including their involvement in slavery and genocide—in this intricately researched account of the most universal subject. –ES

David Shields, The Very Last Interview

NYRB, March 29

It’s been a dozen years since Shields published Reality Hunger, his controversial “manifesto” of the literary remix, which I first loved, and then pooh-poohed, and then sort of loved again, but regardless have continued to think about ever since. This new book is a return to the Reality Hunger energy: the portrait of a writer as an interview subject, made up of the thousands of questions Shields has been asked over the last twenty-five years—reorganized, rewritten, and with their answers entirely omitted. The result is sometimes annoying, sometimes funny, sometimes existentially provoking—like a self-deprecating Lyn Hejinian’s My Life for writers. –ET

Megan Mayhew Bergman, How Strange a Season: Fiction

Scribner, March 29

Megan Mayhew Bergman is one of the best authors out there for chronicling our tangled, intimate, complicated relationship to the natural world; her elegant, lyrical prose documents an evolving crisis and our incorrigibly human responses to it. She’s published widely on the climate crisis for outlets including The Guardian and The Paris Review in addition to authoring Almost Famous Women and Birds of a Lesser Paradise, among the rest of her extensive work. Now, I’m eagerly awaiting her new collection—consisting of short stories and a novella—which features characters as they navigate landscapes natural and emotional and reckon with the echoes of history in their daily lives. –CS