Lit Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2021

228 Books We're Looking Forward to This Year

Well, we waited and we waited and we waited and finally it happened: 2020 came to a close. Now that it’s officially 2021 . . . do you feel any better? Marking time the way we do may be arbitrary, but at least this year brings some hope: a Covid-19 vaccine, an official end to the toxic Trump presidency, and of course, on exactly the same level as the previous two items on the list, lots of good books to read. So because we really can’t help you with the vaccine or the virulent shoo-ing, we will now present the 2021 releases—fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and otherwise—most eagerly anticipated by the Literary Hub staff.

Consider this a snapshot of the year to come in books—or the first half of the year, anyway. Some of these we’ve already read, and some we haven’t (yet), but we think you should probably know about all of them. After all, we still have a while to wait for all those good (or at least better) things that 2021 is supposed to get for us. Why not dive in?

JANUARY

Gretel Ehrlich, Unsolaced: Along the Way to All That Is, Pantheon (January 5)

Ehrlich’s 1985 collection The Solace of Open Spaces has become a classic of American nature writing, a celebration of life in Wyoming and the American West at large. That’s enough reason on its own to be excited about her new work, a sort of “bookend” to Solace, this one focusing on observations chronicled and people met while traveling around a world latticed by climate change. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Una Mannion, A Crooked Tree, Harper (January 5)

Una Mannion, A Crooked Tree, Harper (January 5)

People have been raving about Una Mannion’s debut novel and, by the sounds of it, with good reason. Billed as “a portrait of a fractured American family dealing with the fallout of one summer evening gone terribly wrong,” it’s a suspenseful coming-of-age tale, set in rural Pennsylvania in the summer of 1981, that begins with an overwhelmed widow ordering one of her daughters to get out of the car and walk home… I have already pre-ordered my copy. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Mateo Askaripour, Black Buck, HMH (January 5)

Askaripour’s debut is a satirical send-up of startup culture—styled as a manual for would-be Black salespeople—in which 22-year-old Darren snags a job at a cult-like company where he is the only Black employee. “The turns in this story are half-absurd, half jaw-dropping, and a whole heaping of crazy,” Darren tells us; with all the comparisons to Sorry to Bother You and The Wolf of Wall Street, I would expect nothing less. –ET

Robert Jones, Jr., The Prophets, Putnam (January 5)

The creator of Son of Baldwin, a widely-followed social media platform that fosters critical conversations on race, gender, class, and other intersecting identities and sociopolitical positions, has brought us his debut novel The Prophets, which follows the forbidden relationship between two enslaved young men working on a Deep South plantation. Described as having a “lyricism reminiscent of Toni Morrison,” Jones, Jr.’s novel reinvigorates familiar themes of pain, suffering, intimacy and love with crucially different orientations, conjuring the voices of the enslaved and slavers, showcasing the power and fragility of love. –Rasheeda Saka, Editorial Fellow

Koa Beck, White Feminism, Atria Books (January 5)

A combination of history and cultural reporting, Koa Beck’s exceptional White Feminism looks at what has passed for “advancement” when it comes to feminist causes, which have too often excluded those who most urgently need advocacy. Following her work on gender, justice, and power at Vogue, Jezebel, and WNYC, Beck now challenges us to rethink feminist discourse and asking what opportunities will open to us in the process. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Anna North, Outlawed, Bloomsbury (January 5)

In an alternative version of the American West in the 1890s, a newly married midwife’s daughter finds she cannot conceive and runs away to avoid being burned as a witch—first to a convent, and then to the Hole in the Wall Gang, which turns out to be a handful of nonconforming outlaws led by a nonbinary person known only as “the Kid,” who are all hoping to create space for themselves in the hard, weird world. Described variously as The Handmaid’s Tale meets Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Foxfire meets True Grit, this promises to be a feminist Western like we’ve never seen. –ET

Ashley Audrain, The Push, Pamela Dorman (January 5)

In Ashley Audrain’s slow-burn suspense thriller about motherhood, Blythe Connor doesn’t have much of an idea of how things are supposed to go—after all, her own mother left when she was a young child. She’s determined to be the perfect mother she never had, but she can’t ignore the worries caused by her eldest’s many outbursts. Something seems off about the child, something that she’s never felt about her darling youngest. As her checked-out husband reassures her that everything is fine, Blythe becomes increasingly certain that it isn’t. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken, In the Land of the Cyclops, Archipelago (January 5)

In his first collection of essays to be published in English, literary phenomenon, destroyer of the novel, and describer of . . . everything, reflects on a wide range of topics, from Ingmar Bergman’s notebooks, to the Northern Lights, to Madame Bovary and Rembrandt. While none of Knausgaard’s other books have quite matched the hullabaloo that accompanied My Struggle’s publication, I think his small studies are beautifully poignant (I highly recommend his study of Edvard Munch and the autobiographical seasonal quartet) and I’m looking forward to this collection. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Chris Harding Thornton, Pickard County Atlas, MCD (January 5)

In the midst of a heat wave in 1978, the residents of Pickard County, Nebraska, are finding it hard to keep a cool head. When the family of a long-missing child decides to finally erect a headstone, it provides not comfort but catalyst to the townspeople, as long-simmering rivalries and resentments spark into full-size wars. Chris Harding Thornton has crafted a lyrical ode to a harsh landscape that deserves its place in the canon of rural noir. –MO

Mariana Enriquez, tr. Megan McDowell, The Dangers of Smoking In Bed, Hogarth Press (January 12)

A woman is a heartbeat fetishist; two rock fans rob their idol’s grave; a rotting child’s bones are excavated and reanimated. These stories are macabre and surreal, but not for nothing—they point at frightening, unspoken truths about illness, lust, and morality. As John Freeman put it, “No one writing today creates this smoke and this much fire from such small spaces.” –Walker Caplan, Staff Writer

George Saunders, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, Random House (January 12)

Consider this a class in a box—a book-shaped box, obviously. In it, Saunders, who teaches at Syracuse University’s MFA program, unpacks seven stories by 19th-century Russians (Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol) that all lend themselves toward thinking about the short story form, and, not to put too fine a point on it, toward writing your own short stories (there are also a few exercises within). Saunders writes in the introduction: “The main thing I want us to be asking together is: What did we feel and where did we feel it?” Which makes it a book for readers as well as a book for writers. –ET

Marcos Gonsalez, Pedro’s Theory: Reimagining the Promised Land, Melville House (January 12)

Marcos Gonsalez’s writing bridges history, the present day, and the world of the imagination to bring us the stories of many Pedros—their dreams, goals, and daily lives—and their individual journeys toward fulfillment as they navigate life in America. Told through “reminiscences, speculations, and reckonings,” this is an unforgettable book from an extraordinary writer. –CS

Madeleine Watts, The Inland Sea, Catapult (January 12)

The unnamed narrator in this novel works at an emergency call center in Australia (the equivalent of 911), letting the tragedies of her fellow humans, and her dying planet, wash over her, while subjecting her own body to more and more dangers. Kirkus called it “magnificently uncomfortable,” which is exactly what I like in a novel. –ET

Victoria Gosling, Before the Ruins, Henry Holt (January 12)

Gosling’s atmospheric thriller is centered on a fabulous, abandoned estate, where four strangers on the cusp of adulthood once spent a magical summer exploring, bonding, and playing increasingly dangerous games. Decades later, one is missing, and the others must reopen old wounds in order to track down their errant friend. Gosling uses her richly ruinous setting as a jumping off point to examine class, innocence, morality, and loss. –MO

Olga Grushin, The Charmed Wife, Putnam (January 12)

I’m always here for twisted literary retellings of classic fairy tales—in this one, Cinderella is thirteen and a half years into her marriage to Prince Charming, and feels the need to seek the help of the local witch to fix what’s gone wrong. . . that is, she wants to kill him. Sign me up, baby. –ET

Kevin Barry, That Old Country Music, Doubleday

(January 12)

There are no bad Kevin Barry books. There are no sedate Kevin Barry books. Every darkly-soulful tragicomedy he produces—be it a novel or a short story collection—is a wild, electrified beast of language that throws you up on its back as it dances with manic glee around the lonesome, haunted west of Ireland landscape. Having said all that, Barry’s latest collection is (at times) a somewhat quieter affair—a touch sweeter and more melancholic in tone—but the stories in That Old Country Music have all the hypnotic pathos and inimitable linguistic verve of Barry at his very best. –DS

Torrey Peters, Detransition, Baby, One World (January 12)

Detransition, Baby is basically about a love triangle, only there’s nothing basic about it: Reese and Amy are two trans women in love, until Amy detransitions, becomes Ames, and starts sleeping with his boss, Katrina—who soon reveals she’s pregnant. Andrea Lawlor called it “an unforgettable portrait of three women, trans and cis, who wrestle with questions of motherhood and family making.” It’s also definitely one of the most hyped debuts of the season (Peters is the author of two previous novellas, but this is her first novel); I can’t wait to see how it all turns out. –ET

Andrea Pitzer, Icebound: Shipwrecked at the Edge of the World, Scribner (January 12)

After doing the research for her last book, One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps, one assumes that Andrea Pitzer needed to decompress a bit with the next one, which is probably why she decided to write a history of a late 17th-century polar explorer whose inability to find the North Pole was matched by his crew’s inability to take down a polar bear (at least, with their first shot). While most of the recent wave of polar exploration sagas have focused on later, and much better-equipped, expeditions, Pitzer goes further into the history of seafaring, taking us on a journey with Dutch merchant Barents and his crew as they set out ill-prepared for any of their three voyages, and end up shipwrecked for an entire winter on their third. I devoured this book over a snowy weekend, as should everyone! –MO

Danielle Geller, Dog Flowers, One World (January 12)

I’ve loved every essay I’ve read from Danielle Geller, so I was thrilled when I learned that she’s publishing a memoir this year. Described as a “photo-lingual” work, it archives her mother’s belongings in an effort to understand her relationship to the Navajo reservation and the choices that both mother and daughter made—sometimes with no other options—as they grew up amid poverty, colonization, and a complex family history. –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Gabriel Byrne, Walking with Ghosts, Grove (January 12)

The first memoir in a quarter century from the iconic Irish actor and star of star of Miller’s Crossing, The Usual Suspects, and HBO’s In Treatment, Walking with Ghosts is the story of Byrne’s working-class boyhood in 1950s and 60s Dublin, his battles with alcoholism and depression, his abuse at the hands of the Catholic Church, and his reflections on Hollywood stardom. It’s an extraordinary book—poetic and unflinching, deeply sorrowful but also alive with great wit and tenderness. As far from the paint-by-numbers movie star memoir as you could possibly imagine. –DS

Nadia Owusu, Aftershocks, Simon & Schuster (January 12)

I can’t begin to tell you how excited I am for this book. Owusu, a 2019 Whiting Award winner, has written a memoir about her nomadic childhood and the years she spent grappling with uncertainty, the loss of her father, and her identity as a young woman. Aftershocks is deeply intimate, heartbreakingly honest, and a book that will likely reverberate throughout our hearts and minds long after we’ve finished reading. –RS

Mark Leyner, Last Orgy of the Divine Hermit, Little, Brown (January 19)

Even the elevator pitch of Last Orgy is mind-bending. An optometrist’s patient reads an eye exam chart featuring an anthropologist’s ethnography of the Chalazian Children’s Theater, which details a night out drinking with his daughter at Chalazia’s #1 spoken-word karaoke bar, where patrons perform spoken-word karaoke based on the Chalazian folktale of . . . a drunken father who hints to his daughter that he is dying . . . by telling a story of a father talking to his daughter . . . which the anthropologist and his daughter then perform. Best to experience it ourselves; Publishers Weekly calls it “an exhilarating and grotesque fever dream,” and I’m excited for the ride. –WC

Richard Bradford, Devils, Lusts and Strange Desires: The Life of Patricia Highsmith, Bloomsbury (January 19)

Richard Bradford’s new work about Patricia Highsmith isn’t a straightforward biography, but rather a literary exploration of Highsmith’s many destructive affairs and the influence they had on her dark classics. I’m sure this isn’t news to the folks reading this blurb, but Patricia Highsmith was a psychopathic, racist, antisemitic, alcoholic misanthropist who preferred snails to people, slept with seemingly every artistic lesbian of the 20th century, and vacillated between idolizing her partners and bringing them close to suicide. Also, she played a drinking game at Yaddo with Chester Himes and a British poet that involved consuming over ten martinis in a single night. Damn, Patricia. –MO

Alina Bronsky, tr. Tim Mohr, My Grandmother’s Braid, Europa (January 19)

A week doesn’t pass when I don’t think at least once about Alina Bronsky’s savage, hilarious 2011 novel The Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine, so I’m here for anything new she writes. She is at her best when evoking family dysfunction and powerful, mean old women, and both aspects are promised here, as we meet Max, who lives with his grandmother—a former Russian primadonna with a bad attitude—and his grandfather—who is clearly in love with their neighbor, soon to have a baby who looks just like him—in Germany. Sounds like a riot, as ever. –ET

Ellie Eaton, The Divines, William Morrow (January 19)

Eaton’s debut combines three of my favorite things—boarding school, “vicious” teenage girls, and long-buried secrets that haunt for years—in a literary novel that comes studded with blurbs from writers like Sarah Perry, Rufi Thorpe, and Kimberly King Parsons. So yes, it may be unbearably on brand for me, but that doesn’t mean I anticipate it any less. –ET

André Aciman, Homo Irrealis: Essays, FSG (January 19)

Aciman’s latest essay collection is a must-read before you cozy up again to Call Me By Your Name. Homo Irrealis offers meditations on the creative mind, time, and what it means for artists to grapple with the “here and now.” From the subway to empty Italian streets, Aciman reflects on the power of imagination on our memories and how we move through the world. –RS

Matthew Salesses, Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping, Catapult (January 19)

This is one of those books you hear about and wonder how we’ve lived so long without it. Required reading for creative writing teachers (and, I imagine, affirmative reading for those who have been personally or professionally hurt in whiteness-centered workshops), Matthew Salesses’s Craft in the Real World is an argument and a guide for upending the traditional workshop model and our conceptions of craft. –ES

Nnedi Okorafor, Remote Control, Macmillan-Tor/Forge (January 19)

The Hugo-award winning author Okorafor is coming to us with a sci-fi novel about a young girl who turns into Death’s adopted daughter. She searches for meaning in the world and for the person she was before her transformation. Will she find what she’s looking for or ultimately succumb to the fate Death has in store? Let’s find out. –RS

Ladee Hubbard, The Rib King, Amistad (January 19)

I adored Ladee Hubbard’s The Talented Ribkins, which reinvents superpowers to be the cunning tools of the oppressed, merging trickster legends with modern superheroes. Now we get to read about the Ribkins’ controversial ancestor, The Rib King, who begins the book as a loyal servant to a down-at-the-heels white family, then morphs into the caricatured brand ambassador for a popular condiment, all the while seeking revenge against those who destroyed his Florida hometown. –MO

Joan Didion, Let Me Tell You What I Mean, Knopf (January 26)

If I’m being completely honest, Joan Didion could publish an anthology of her grocery store lists, and we’d still be interested. She’s our patron saint! What can I say?! Thankfully, Let Me Tell You What I Mean promises to be way more substantive than that: the twelve pieces collected here stretch back to her earlier days, giving us a glimpse into everything from WWII veterans reunions to Gamblers Anonymous meetings with her signature style and precision. Classic Joan. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Tove Ditlevsen, tr. Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman, The Copenhagen Trilogy, FSG (January 26)

These three slim novels, which are being published separately as well as collected into a single volume (the covers are so good that you probably need all four books), are variously described as “memoirs” and “autofiction,” but like most genre distinctions, it doesn’t matter in the least. Taken together, they tell the story of Ditlevsen’s ascent from frustrated child to frustrated writer to, in the third book, a woman frighteningly and overwhelmingly controlled by her addiction. The writing is cool and sometimes funny and strangely affecting, even at its plainest; you’ll speed through and then wonder what happened to you. –ET

Charles M. Blow, The Devil You Know: A Black Power Manifesto, Harper (January 26)

Honestly, Charles M. Blow deserves some kind of preemptive award for making it through 2020 without full-on strangling any number of his colleagues on the New York Times op-ed page (you know who I’m talking about). So it’s doubly impressive that he managed to write a book through it all (the “race book,” apparently, that he never really wanted to write). Framed as a manifesto, The Devil You Know is a call to Black political power that recognizes that the white political establishment, no matter how well intentioned, just isn’t going to fix the institutional white supremacy that has benefited them every minute of their lives. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Avni Doshi, Burnt Sugar, Overlook Press (January 26)

In Doshi’s debut, shortlisted for the Booker Prize, an artist wonders whether her mother—only middle-aged—is going mad. This novel is as pleasurable as it is discomfiting; and as more truth spills out and as the family grows, things only get weirder and weirder. The whole book is caustic and heartbreaking in equal measure, but the last gesture is particularly unforgettable: a spiraling, feverish set piece that shook me to my core. A daring, excellent first novel. –ET

Sarah Jaffe, Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone, Bold Type Books (January 26)

“Do what you love” sounds like a great idea in theory; in practice, Sarah Jaffe argues, it’s an attitude that allows employers to continue exploiting workers while rendering the problems of capitalism invisible. This year made the already-clear flaws of our economic structures more obvious than ever and brought a new urgency to the long fight of labor protections; Jaffe’s book provides a welcome critique of what brought us here and ideas for how to move forward. –CS

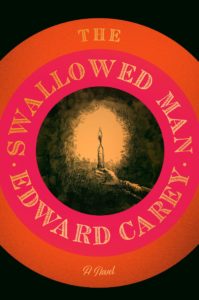

Edward Carey, The Swallowed Man, Riverhead (January 26)

Edward Carey and Elizabeth McCracken are Austin literary royalty, so it’s exciting that both have a new book out this year. Carey’s latest is a retelling of Pinocchio with a vast well of sympathy for the lying puppet’s lonesome and troubled creator, who spends much of The Swallowed Man contemplating his sins while in the belly of a whale. The Swallowed Man also has plenty of Carey’s trademark illustrations! –MO