What Really Goes On in a Writer’s Notebook?

Danielle McLaughlin on the Process of Writing Her Latest Novel

I’m someone who’s slow to throw things out. In the room where I write, as well as the usual writer detritus, there’s a doll I got for Christmas the year I was five, rolled up posters from the walls of flats I rented in my teens and early twenties, and an empty prosecco bottle from when my husband proposed. This tendency to hoard is a tricky habit for someone who likes to write longhand. I keep all my drafts and so, over the years, I’ve accumulated notebook upon notebook.

Longhand is how I need to write when I’m in the early stages of a project. Even after I’ve moved a story onto computer, every once in a while I’ll print out a typed draft to scribble on, teasing out knots, adding and subtracting. Longhand is where problems get solved. All this adds up to a lot of paper, and when it overspills the space available, it gets carried up to the attic. So it’s in the attic I find myself the Saturday before Christmas, ducking beneath the low beams, dodging cobwebs, as I make my way with a torch to the farthest corner in search of the notebooks in which I wrote The Art of Falling.

I like my notebooks to resonate in some way with whatever I’m working on. The covers of the ones I used for The Art of Falling have lots of blue and green hues, the influence of the West Cork coastal setting, perhaps, which may also have prompted me to choose the notebooks with insects and dense vegetation. There’s a notebook with a very lovely octopus in gold foil against a blue background. I associate the octopus with a series of sea-themed pieces made by Robert Locke, the sculptor in the novel. There are also more prosaic looking school copybooks that I picked up on a summer holiday in Italy. I remember being very taken with the quality of the paper, as well as by the words in Italian on the front—quaderno, nome, cognome. School copybooks make an appearance in The Art of Falling, and now I find myself wondering: which came first: the idea or the notebooks?

I write in any colored ink that is to hand—black, green, blue, purple, red. Here and there, I can see where the pages got wet and the ink ran, leaving a rainbow stain. My notebooks get hauled about unceremoniously from kitchen to café to beach to car. Recipes have made their way onto the margins, measurements of flour and sugar. Elsewhere, I see that I’ve taken notes on a too-good-to-resist conversation overheard at a café, a very promising and surreal row which included the rather wonderful line: “If you don’t get your ears done soon, I’m going to have to start writing you letters.”

In the notebooks, I don’t just write down the story, I also engage myself in conversation about it. Sometimes this takes the form of quite profound questions like “Is the story of Adam and Eve stored in the Y chromosome?” or “Is this character a magpie or a cuckoo?” Others are more mundane: “What does she do with the ingredients for the tacos?” “Too many Volvos,” “Where are Chapters 12 & 13?” I have, I notice, a tendency to be hard on myself. “Weed out stuff!” I tell myself, “Fix the sanctimonious sentence.” In response to an idea jotted down to write “a story within a story; a prose-poem within a story?” I see that I’ve answered: “If you want to write poetry, write poetry. This is a novel.”

In contrast, there’s a page comprising a list of life-affirming exhortations and aphorisms, accompanied by Latin translations. Perseverance conquers; In counsel is wisdom; Let Courage be thy test, and so on. To a stranger’s eye it might look like the novel took a sudden swerve into a self-help manual, but I was in fact searching that day for a suitable motto for the school that my protagonist’s teenage daughter attends. I decided, finally, on “To be, rather than to seem” (Esse quam videre) a sentiment which I felt went to the heart of much of what my protagonist was struggling with. It would become the novel’s opening sentence.

This tendency to hoard is a tricky habit for someone who likes to write longhand. I keep all my drafts and so, over the years, I’ve accumulated notebook upon notebook.I rarely add dates to what I write in the notebooks, but leafing through them now I notice that in the margin of one I’ve scrawled 13-14 February 2015. I would have been away then at a writers retreat in Cill Rialaig, a restored famine village on the edge of windswept cliffs in Ballinskelligs, Co. Kerry. Desolate, stunningly beautiful, and steeped in history, it’s my kind of writing retreat, a very unsocial one, with each writer residing alone in their own small cottage, and no organized activities. I’d often work until the early hours of the morning, sitting by the turf stove, drawing on the soup of creative energies left by the writers and artists and famine-era families who’d occupied this space before me. I was in the very early stages of a novel set in a lakeside development of cabins, with tensions developing between two women when someone from their past re-surfaces. That night, and early morning, of February 13-14 I knew I’d had a breakthrough when I jotted down: “Mix these characters and the Chalk Sculpture?”

The Chalk Sculpture was a short story I’d been writing and re-writing, in various incarnations, for a few years. It first sparked into life at a workshop I took with the Irish novelist, short story writer and poet Nuala O’Connor at Waterford Writers Weekend in 2012. Each version of the story differs in fundamental ways, but there are also elements common to all of them: the Chalk Sculpture itself, for instance, as well as infidelity, complex relationships between women, and a wild and isolated landscape. None of these versions of the short story were ever published. To my frustration, there continued to be something about it that eluded me. That something was supplied in Cill Rialaig when I merged the story with the early outline of the novel. Re-reading the draft short stories now, I’m intrigued by how completely certain ideas and scenes have survived over the years to inhabit the final draft of The Art of Falling.

The prompt I got in the workshop in 2012 was a piece of broken pottery. As I held it in my hand I remember noticing its white chalky edges. The sense of brokenness that emanated from it went beyond the piece itself, and in my head an image formed of a woman in difficulty, struggling to climb a coastal path. I’ve kept the piece of paper I did the writing exercise on. Many of the words I threw down quickly to describe the path—”smooth,” “white,” “a soft curve”—are words that would later feature in my descriptions of Robert Locke’s best known work in the novel, a piece bearing the same name as the title I gave my rough jottings that day: the Chalk Sculpture. Now, working on a very messy draft of my next novel, I tuck the workshop scribbles into the box containing my author copies of The Art of Falling, a reminder that the journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.

__________________________________

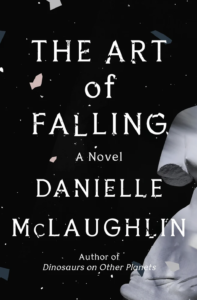

The Art of Falling by Danielle McLaughlin is available now via Random House.