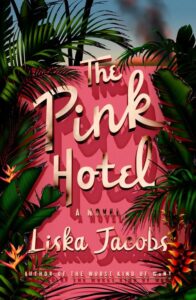

Liska Jacobs on Leaving Los Angeles, City of “Impermanence and Unreliability”

Finding Kinship with Eve Babitz and Joan Didion

On the flight to Berlin I drank a cup of hot black tea with two packets of sugar for the shock. I had left Los Angeles, my home. A place that is as much a part of me as my soft tissues and organs. I was flying east, moving away from it. I was moving forward (in time), I was moving backwards (in history). I was not sure I was really there, except for that tea. Which was warm in my hand and sweet in my mouth.

I was returning to the city my great grandfather had fled before the first world war, almost a hundred years ago to the month. Time is a flat loop indeed. Except it’s not. Our lived experience, what we see as our now, is only one slide of space-time. According to Albert Einstein, who ninety or so years ago refined and confirmed his theory of relativity while visiting the Mt. Wilson Observatory, which for the last seven years I could see from the lawn of our Pasadena apartment—past, present, and future all an illusion.

Berlin became Los Angeles’ 6th sister city in 1967. I don’t know what my great-grandfather was doing that year. Living in Brentwood probably, caring for my father because his own son, my grandfather, was a heroin addict. But I do know that late that summer, patron saint of LA cool, Joan Didion was making trips from Berkley to Haight-Ashbury to mine the acid-heads and runaways in what would become Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

Meanwhile, same year, Eve Babitz—Hollywood muse incarnate—was sleeping with rock stars and movie stars and wrapping up a collage for the cover of Buffalo Springfield’s second album. Babitz’s Los Angeles would become Eve’s Hollywood, a novel Didion would blurb after her own novel, Play It As It Lays, also set in Los Angeles, became a critical and commercial success.

My Los Angeles isn’t their Los Angeles. There are as many versions of LA as there are people currently thinking about it. But I saw and felt a connection to Didion and Babitz’s Los Angeles, and when someone’s version of the place you call home resembles parts of your own, you feel a certain kinship because what are we if not an extension of the place we inhabit?

Yet Joan Didion and Eve Babitz could not be more different from each other. Berlin and Los Angeles different. Fifteen hours by plane different.

Joan Didion was raised in Sacramento. She went to Berkley and traded California for New York. Her Los Angeles is affluent and white and privileged, I know where that Los Angeles lives even if it is not my own. But her Santa Anas winds are my Santa Ana winds. In Slouching Toward Bethlehem she describes them as violent and unpredictable. “The entire quality of life in Los Angeles accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability,” she writes. “The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.” Yes, I know that place. I know its dry heat, the brisk howling wind. It kicked up almost as soon as I stepped foot on that plane. Red flag warnings for days.

Eve Babitz was West LA Bohemian with a pedigree. A blonde bombshell at Hollywood High with Igor Stravinsky for a godfather. When I think of her, I think of my parents’ Los Angeles—of my father and his sister back in Brentwood with my great-grandfather, only now they’re teenagers in hot rods, cruising the Sunset Strip. I think of my Aunt who Kim Fowley once called “the sex goddess of Hollywood;” who one night with Joan Larson, not yet christened Joan Jett, put henna in their already dyed black hair, giggling, high on quaaludes or LSD or whatever. Stories so outrageous that they must be true, much like the ones Babitz tells, all woven into this version of Los Angeles that beats inside of me.

“I wouldn’t leave LA if the whole place tipped over into the ocean,” a friend declares in Babitz’s Slow Days Fast Nights. Babitz describes this friend as “too tough and too fragile for anyplace else.” In The White Album, Didion writes, “A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that they remake it in their own image.”

When a week before I boarded the plane to Berlin, Eve Babitz and Joan Didion died within days of each other, my grip on time and space began to slip. I had lived in Los Angeles all of my thirty-eight years, and in all that time I took for granted that they occupied the same space. Maybe Didion was in New York, fine. And Babitz was a recluse somewhere in the Hollywood Hills. But they had driven the 101 and 5 freeways, they knew those canyons and freeways. They saw the same skyline I saw. With their deaths, in a sense, their Los Angeles died with them.

The relationship between writer and reader is a limited transaction. The moment we read, the writer’s words are no longer their own. We bring our own baggage to the page. There is no way for me to inhabit their Los Angeles outside of their writing, just as you cannot inhabit mine. This realization scared the shit out of me. Not just the limits of language but after I left, would my Los Angeles cease to exist too? How could I keep it alive a little longer?

I started driving Mulholland sometimes three or four times a day, crisscrossing freeways more often than Maria in Play It As It Lays. “She drove it as a riverman runs a river…” except I wasn’t a riverman, I was a time traveler. Ask Einstein, who finished his theory of relativity while teaching at a Berlin University. Time goes slower for those who are closer to a strong gravitational force, which meant the harder I pressed on the accelerator, the slower time moved for me (the difference is infinitely small but I was going to take what I could get).

Maybe if I drove fast enough I could collapse time altogether. My dad could be one of the children at the bus stop on Sunset Boulevard, Steve McQueen and James Garner still racing their mini coopers in the predawn light (one of my dad’s favorite childhood stories). I was driving those same bends at sixty miles per hour, switching lanes and weaving around construction trucks and the tourists in their rented convertible—taking that turn around UCLA so fast my tires pealed. Faster, faster still—maybe Babitz is screwing her rock star in a suite at the Chateau Marmont during the 1992 riots; Didion watching that B-actress slink across the backyard of a Hollywood home, the character of Maria beginning to form in her mind.

Maybe somewhere in Westwood my great-grandfather is collecting properties so that his children and their children would never have to live in poverty in Eastern Europe again—ha. But if I’m collapsing all of it, then as fast as that man amasses his real estate fortune, my father and his father burn through it like wildfire, which brings us back to me. Driving like a mad woman through the canyons trying to reach back and touch the past while outrunning my future.

On Mulholland, if I drove fast enough, it was as if nothing moved. Not the city below, not the sky, or the light, only the road coming and going under my tires. In some equation, on a Cal Tech dry erase board probably, I was doing it, I was standing still, untouched by time. Yet in another, I was already gone. The plane had already taxied and taken off. I was just a ghost passing through, moving from one side of the city to the other, east to west, west to east, and back again.

My great-grandfather’s name was Paul. And he was dead long before I came around. But I’m told I’m tall like him, dark like him. He came from the Austrian Hungarian empire via Berlin and did not speak of his family or his past. He practiced his religion in private. No one knows what happened to his Torah, the pages worn thin. He did not teach his children German, or Polish. His fortune may be gone but at least he’s buried in Hollywood Forever cemetery, and maybe that’s the only real estate that matters.

I am in Berlin now. He must have known this gray city as well as I know my golden one. He must have been able to close his eyes and feel its pull. I worry that if events converge and circle one another then we’re all just exactly where we were last year, or where our ancestors were a century ago. Maybe time means nothing at all. It doesn’t matter how fast you drive.

My first week here I went to a bookstore (where else does a writer go in a new city?) and I found Joan Didion’s last published book, Let Me Tell You What I Mean. It’s a collection of her earliest essays, published last, of course, of course. Eve Babitz too, her final work, I Used to be Charming, is a collection of essays written between 1975 and 1997. The past speaking to the present, the present already in the past.

Another feature of Einstein’s theory is atemporality. It’s the idea that the recording of our surroundings allows us to reach back and experience what we consider the past. It means our vast accumulation of literature, film, music, memes—it increases our ability to transcend time. It means, when I read Didion or Babitz, I am time traveling. Their Los Angeles flickers alive. Not gone forever.

It means that if I sit here in Berlin and write about the 5 and 134 interchange, how its curve is gentle, I’ve driven it a million times. I like how the fast lane becomes the slow lane and you have to cut across three lanes to get to the carpool, and you have to stay calm because the first exit is Forest Lawn, the wide expanse of hillside where we bury our dead. Cemetery on one side, Griffith Park on the other, a horse ranch with real cowboys opposite, the Valley coming at you fast. Santa Ana winds pulling at the wheel. It means I can be here, and you there, and together my Los Angeles is preserved in something not quite amber, but just as precious. And there it stays, waiting for my return.

_____________________________

Liska Jacobs’ The Pink Hotel is now available from MCD.