Light the Fire and Fan the Flames: Surviving China’s Cultural Revolution

Kent Wong on a Childhood Amid Unstable and Dangerous Times

The Cultural Revolution began with the creation of a “big-character poster” by a young philosophy lecturer, Nie Yuanzi. A big-character poster was a wall-mounted poster that employed large Chinese characters as a means of protest. Nie posted hers in Beijing University, the cradle of the student political movements. A hard-core Marxist and Maoist, Nie was angry at the pragmatism of President Liu and Deng and with the direction the country was heading.

President Liu and Deng had steered the country away from Mao’s ideas such as the “Free Big Wok Meal.” They had promoted intellectuals, such as professors and capable educators, to run the universities, regardless of whether they were “white cats” or “black cats.” To Nie, this was Chinese revisionism akin to that of the Soviets, and against Mao’s teaching. In her big-character poster, she accused the president of Beijing University of running the school in a bourgeois manner. She implied that leaders higher up in the central government were the culprits. Her complaint fell on deaf ears, and this angered Mao.

On August 5, 1966, Mao wrote a blistering short piece in support of Nie Yuanzi’s poster. Called my first big-character poster—bombard the headquarters, it was published in every newspaper. In it, Mao stated that “some leading comrades from the central down to the local levels are adopting the reactionary stand of the bourgeoisie.”

I was shocked by his words, and his use of phrases such as “bourgeois dictatorship” and “white terror” to describe the forces that had struck down “the surging movement of the great Cultural Revolution of the Proletariat.” Who were these bourgeois dictators? It was obvious to many that Mao meant none other than President Liu and Deng.

After Mao’s article ran, the front pages of all newspapers published a full-page shot of Mao standing on the Gate of Heavenly Peace waving to jubilant students in Tiananmen Square. Mao and the students wore army uniforms and the same red armband with the words red guard in Mao’s handwriting. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was launched, and China would never be the same.

Within days, Red Guards, identified by their red armbands, were organized in many cities. Newspapers printed images of them marching in the streets shouting angrily. The graffiti safeguard chairman mao with our fresh red blood! was posted everywhere. The university students who were part of the Red Guards took the lead. Within days, Red Guard groups from every high school, cultural institute, and the performing arts were organized. Soon, young workers joined the movement. The only people absent were peasants, soldiers, policemen, kids, and old folks.

Then the newspapers reported that Mao had ordered the Red Guards to “light the fire and fan the flame” all over the country by traveling around and spreading his words. This was called the “Big Link-up.” All travel by train would be free for Red Guards, but because they had no identity cards, everyone could claim to be part of the Red Guards and get a free ride. No conductor dared question anyone’s Red Guard status, so they let everyone board for free.

The Big Link-up brought the first Red Guards from Beijing’s 101st High School to my school. My elite classmates must have known something was coming. They moved quickly to put on army outfits and armbands and called themselves the East Wind Red Guards. They then selected those from other Red families to join them.

My sister Jing was a third-year medical student by then, and Lily and Ning were in junior high; they had never been interested in politics. Bun was in elementary school and therefore too young for politics. Mommy told me I was the only one she worried about.

“I don’t want you to join the Red Guards!” She warned me.

“I can’t. Red Guards are for those from the Red families. I’m from a Black!”

The East Wind Red Guards took over the school. I didn’t know where the teachers, the principal, or the party secretary had gone. Where were they hiding? The East Winds quickly found them and ransacked the party secretary’s office, exposing all students’ dang’an. Papa’s past was finally revealed.

Using the dang’an, the East Winds prepared a blacklist of teachers to be punished. Their “crimes” ranged from political to nonpolitical, such as extramarital affairs. Then all students, Red and Black, were expected to write big-character posters against them. We wrote day and night, covering every wall in the school.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was launched, and China would never be the same.

Meanwhile, the East Winds set up a Cowshed in our school—in this case, a classroom guarded by East Winds 24 hours a day. The windows and door were blocked with desks and chairs. One by one, the teachers whose names appeared on the blacklist were jailed in the Cowshed. They were told to write out confessions to their crimes, which had been announced on the big-character posters all over the school.

What happened outside our school was even more frightening. The newspapers revealed the shocking news that Red Guards had placed President Liu and his “running dog” (accomplice) Deng under house arrest in Beijing. Many leaders of the central government in Beijing were taken down, and in Canton, Red Guards arrested the governor and party secretary. In universities, schools, factories, and institutes, the enemies were always the managers and administrators and professors and teachers from Black families. They were the capitalists, revisionists, and any other -ists, and their “running dogs”—the Red Guards succeeded in jailing them in Cowsheds without firing a shot.

I read the big-character posters written by my classmates. They all used the same technique, called shang-gang shang-xian—giving a person’s innocuous words or actions such political significance that nothing short of a beating or torture will suffice to calm the public’s hatred and anger. One of our teachers had relatives in Hong Kong who bought him a British BSA three-speed bicycle that the Chinese called a “Three Guns” bicycle. It was an elegant bike, and we all envied him. He loved it dearly and polished it daily. Then a big-character poster denounced him as a capitalist because he loved this British product. If he loved his British bicycle, he must love the British, the thinking went, and he must not love China. Therefore, he was a capitalist and a traitor. That was definitely shang-gang shang-xian. To the Cowshed he went!

The rumor mill was working overtime during this period. Neighbors spoke about the downfall of the famous, local and nationwide. Mommy was more aware of what was happening in the city than I was.

During lunchtime, the kids came in droves to read the posters. They read only those that exposed extramarital affairs, chatting and giggling as they read. And when a new poster appeared, they didn’t miss a beat. They’d go home and tell their friends and parents, and their friends and parents in turn would tell others. Watching them, I recalled the kids stomping on those sparrows while shouting, “Down with the counterrevolutionaries!” We, the most intelligent and the fittest of all living creatures, always seemed to find joy in others’ misery.

The teachers in the Cowshed were not allowed to go home, and they were interrogated whenever their captors felt the urge. There was really nothing to ask them; their “crimes” had already been detailed in the big-character posters on the walls. But to keep the revolution going, it was important to offer the interrogators some fun.

The East Winds might not have been the smartest students in school, but they were certainly the most creative at torture. Beating the teachers with sticks and leather belts was boring. Forcing them to crawl and bark like a dog in order to receive food and water was fun. Also, riding our teacher’s precious “Three Guns” bicycle up and down the stairs until it broke into pieces was a special treat, available only at our school. (Savagely cutting a teacher’s hair was considered “mild” and boring; this punishment was usually reserved for the female “monsters and demons.”)

Monsters and demons quickly became the most popular criminal designations during the Cultural Revolution for any counter-revolutionary or capitalist or revisionist or feudalist or whatever other criminal lurked in the minds of the Red Guards at a given moment. The term was effective—instantly conjuring up a visual of evil that could scare the kids, an efficient, one-size-fits-all no-brainer. So, I will use this term from now on for the same reasons.

Compared to other places, the East Winds at my school were “gentler”; no one died in our Cowshed. Rumor had it that Red Guards elsewhere forced their monsters and demons to kneel on the still-burning ashes of books and other offending objects, such as violins. One famous Cantonese opera singer was hit on the back repeatedly with hardcover books while forced to kneel in hot ashes. The books were thrown at him from a balcony several stories above. Every blow brought loud cheers and laughter from the East Winds. Apparently, the singer was guilty of performing an opera that glorified the feudalism of the old dynasties, and he had therefore not followed Mao’s speech given at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in 1942 that demanded that all art serve the workers, peasants, and soldiers.

After the interrogation came the sentencing, which was always quick. A person’s crimes would always be one of the list of crimes—counterrevolutionary, capitalist, revisionist, imperialist, or feudalist—and would have appeared numerous times on the big-character posters against him or her.

Finally, came the climax. For this, a loud, hysterical crowd was required, so everyone, Red and Black, was expected to attend. The bound “monsters and demons” were then lined up to face the crowd. Each one of them wore a large board around his neck, with a red X written over his or her name. The X symbolized a death sentence for the offender’s nonphysical being: his thoughts and beliefs—Mao had not given the Red Guards the order to put to death anyone’s physical being. Of course, physical death was quite acceptable if the “monster and demon” committed suicide or died in the Cowshed “mysteriously.”

Every time a person’s name and crime were announced, the crowd erupted in thunderous shouting of either “Down with… ” statements, with enemies of all kinds mentioned, or statements glorifying Chairman Mao; with the latter, only the best words and phrases would be used. The louder and angrier one’s voice, the more revolutionary he or she was considered. After this public spectacle, the “monsters and demons” were then sent back to their Cowshed, and the torture routine resumed.

We, the most intelligent and the fittest of all living creatures, always seemed to find joy in others’ misery.

Participating in such events made me worry about Papa. In my mind, he could not escape such punishment. I could only pray to Heaven to make him suffer less. For myself, I thought of only two things I could be punished for: Papa’s being a capitalist rightist and the many pictures of me taken in Hong Kong. But I couldn’t do a damn thing about either. What good would it do to worry? I scratched my head and started to feel uneasy about the English word Mommy. My good friends in my class also called my mother “Mommy,” and she didn’t mind. For them, the word was different, fashionable, and had a ring of Britishness to it.

If I’m accused of being unpatriotic, so be it. I can’t deal with all my worries, I told myself, and stopped worrying about using the word Mommy.

“Mommy, have you heard anything from Papa?” I asked her one day.

“He’s safe, so far,” she said. “Heaven blesses his small city. He’s lucky he’s not working in Canton.”

“A small city is better? Why?”

“In a small city, things could go to either extreme.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Go find out for yourself.” Mommy had been impatient lately.

*

All teachers not in the Cowshed were separated from us. I learned that they were studying Mao’s teachings and writing big-character posters against their colleagues. Now in control of the school and the class, the elite East Wind Red Guards turned their attention to their classmates. Overnight, I became one of the “little bastards,” the term they used for those of us from Black families. The expression was based on a tenet of Chinese “wisdom” that said that who your parents were determined who you would become. In the eyes of the East Winds, they were the natural heroes because their parents were considered heroes. Conversely, those from the Black families were little bastards because they had been bred by their bastard parents.

The East Winds told us little bastards that we must align with Chairman Mao and disgrace our parents. As a little bastard, I was expected to criticize Papa’s crimes in front of the class and give personal examples of how Papa had influenced me in the wrong way. All little bastards had to tell the class how they would redeem themselves by applying Mao’s teachings from his “Three Constantly Read Articles.”

Overnight, I became one of the “little bastards,” the term they used for those of us from Black families.

I had expected the day would come when everybody in my class would learn of Papa’s downfall. But for my good friend Hay, he didn’t expect his family secret to be exposed. It was a sad story. When Hay was a baby, his father was executed during the liberation and his mother committed suicide. Hay grew up under the care of his “uncle,” a family friend. Hay’s dang’an didn’t mention his biological parents, but a classmate dug out Hay’s uncle’s history and by chance found out Hay’s secret. When Mommy heard about it, she asked me to invite Hay to the house.

We learned that his biological father had been educated in Paris. Some of his father’s schoolmates later became high-level Communist Party leaders in China. But Hay’s father chose civil engineering in school, and returned to China to build dams for the Chiang government during the Chinese Civil War. Hay’s parents didn’t flee to Taiwan with Chiang before the liberation and were arrested by Communist soldiers. Hay’s father was forced to design and build a dam before being executed; his mother hanged herself afterward. Hay’s parents had sent him away to the family friend before they were arrested by Communist soldiers.

Mommy took Hay in with love, and soon became his godmother. Hay would become the pioneer freedom swimmer and would inspire me during the darkest years of my life.

The Cultural Revolution revealed the darker side of humanity. The worst were the children who reported their parents’ private so-called counterrevolutionary conversations and deeds to the Red Guards and cheered when they were dragged away to be punished. These children shouted revolutionary slogans when the Red Guards roughed their parents up in public. This display of ugliness by my own kind affected me, and I realized that the world was much worse than I had once believed, or wanted to believe, it to be. An animal would not hurt its own parents. How could humans behave worse than an animal?

__________________________________

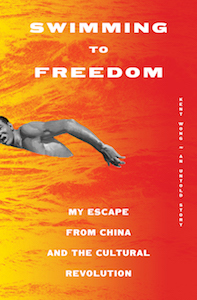

Excerpted from Swimming to Freedom: My Escape from China and the Cultural Revolution. Used with the permission of the publisher, Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. Copyright © 2021 by Kent Wong.

Kent Wong

Kent Wong was born in China. In 1974 he escaped the Cultural Revolution over water to Hong Kong, and shortly after moved to the United States as a refugee. He earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of Washington, his MD at Harvard Medical School, and after a residency at Stanford, he practiced as an anesthesiologist. He is now retired and lives near Seattle.