My mother claims no memory of when or how she taught me to read. But she must have; there was no one else. I had been verbal from the start—babbling, making up songs and singing them to myself. “Maybe you always knew,” she told me recently on the phone, with something that sounded like wonder in her voice. This is how she felt about all three of her children. In her mind, we were extraordinary, rare beings, so remarkable feats should be expected of us. Our abilities gave her the permission she needed to sometimes parent us with distance.

When my mother was a child, there were stretches of time where she longed for her own mother, a short and round sturdy woman with dark coppery skin, wide hips and droopy, heavy eyelids covering almost black eyes. My grandmother, the sole owner of a small blues café and part time nanny with seven other children, would disappear for days without notice, escaping into the arms of new lovers across town or out of state. My mother remembers waiting for her by their front door biting her fingernails, rubbing the bottom tips of her earlobes raw.

The author with her mother.

The author with her mother.

Even though my mother did not become the kind of woman who gave comfort after a fight with a bully, she was my everything. If in any way I turned out interesting, or smart, or funny, or hardworking, it was because she stitched together a quilt of a life for me, in some places fully capable of keeping me warm and whole, and in others, less so, from many disparate strands.

By the time I started kindergarten at Springdale, a public school in an especially black and resource-hungry neighborhood in Memphis, I already knew how to read.

*

About Springdale: I remember my newfound independence, the time I fell on the blacktop and skinned my right knee, Valentine’s and St. Patrick’s Day parties, a reading loft I loved, joining a troupe of Brownies, listening to New Edition with LaKeisha and Precious on a pink tape deck, finding caterpillars.

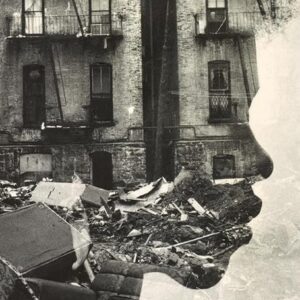

In 2015, a public policy organization said that 38108—the North Memphis zip code of Springdale and the house with green shutters where I lived with my mother, the first place I called home—was one of the most economically distressed neighborhoods in all of Tennessee. Memphis, in its entirety, they noted, was worse off than Baltimore and second to Detroit.

A good portion of black neighborhoods in Memphis, especially those in the north like Hollywood, Douglass, or New Chicago, or in the south like Washington Heights, are blighted. Rows of houses are interrupted by empty, weed-strewn lots, where a home has been condemned, then abandoned, then torn down. There may be an occasional liquor store, a few storefront churches, an oddly shaped, toxin-spewing chemical plant. But we do not have banks, office buildings, no well-known retailers. The schools are often in desperate need of more space. Some have portable classrooms: long, wide trailers propped up on fading red bricks. They need better light fixtures, repairs to the exterior, more books for their libraries.

*

For a few years in the 1990s, Memphis was known as the “murder capital” for its high rates of homicide. The city has long had a gritty, renegade reputation, but the crimes sanctioned by the state itself have proven to be the most enduring. Andrew Jackson, the nation’s eventual seventh president and principal signer of the Indian Removal Act, was one of a group of investors who founded Memphis in 1819. He negotiated purchase of the surrounding land from the Chickasaw Nation. Situated on the Mississippi River, but high on a bluff about 50 feet above the river’s flood plain, the would-be town was geographically ideal for commerce. Cotton and slaves became its livelihood.

Memphis fell to the Union Army early in the Civil War, fueling white resentment that never seemed to give way. Soon after the war ended, white police officers rampaged a South Memphis neighborhood, burning homes and churches, shooting indiscriminately, killing 46 black men, women, and children. Lynchings increased in the years that followed and continued through the early decades of the 1900s (Giddings, 1984). The mainstream press unambiguously approved of the carnage. “Nothing but the most prompt, speedy, and extreme punishment can hold in check the horrible and bestial propensities of the Negro race,” read an editorial in The Daily Commercial.

Former schoolteacher and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett wrote about the lynchings in the black press and in her own publications, providing eyewitness accounts to the crimes, linking the dubious claims of the murderers to white fears of black economic power and sexual autonomy. She fled the city in 1893, relocating to Chicago due to threats on her life.

Ida B. Wells, c. 1893.

Ida B. Wells, c. 1893.

More than 50 years later, the city was still stubborn to black progress. The Supreme Court said in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that separate facilities for blacks and whites were “inherently unequal.” But the Memphis school system’s leaders ignored the ruling until the local NAACP sued, and in 1973, public schools were finally forced to desegregate with a series of mandated busing initiatives.

It was only 13 years after that that I entered kindergarten at Springdale. By then, most students in the school system were black. Defiant white families had abandoned the city’s interior in droves, moving further and further east, creating suburbs beyond the city’s limits, opening and enrolling in new religious and parochial schools known around town as “white flight academies.”

The school board created accelerated programs in some of its locations starting in 1976 to try to stem the tide of white flight (Pohlmann, 2008). In its magnet program, Springdale’s teachers encouraged creativity and individualized learning and play. My mother saw the magnet school as an opportunity, an out, for me.

*

My kindergarten teacher, Ms. Shelley, was a tall white woman with delicate features and shiny, shoulder length brown hair. She wore floral blouses and long dresses with sweetheart necklines, cinched at the waist, flowing a-line down to the knees or just below them. At reading time, Ms. Shelley would pull me away from the rest of the class and give me a different textbook, usually from the third grade class down the hall. She’d sit me at a table alone or out into the hallway, and then leave me on my own to read through a passage as she went back inside. After some time, Ms. Shelley would come back to the hall so that we could discuss my reading.

One day I struggled to get through a passage that I found difficult, so I was still working when she came back. I began to trace the words of the sentences with my fingers to try to force my eyes and brain to move more quickly. “Don’t use your fingers,” Ms. Shelley said then. “You’re too smart for that. You can keep up without them.”

*

In the spring of that school year, my cousin Frank died of AIDS. He was more like my mother’s brother so I called him Uncle Frank. He had been tall and gregarious and was born in Memphis like all of us but moved to Chicago, then San Francisco, as an adult. There he sang in gospel choirs and made a living as a hair stylist.

In photos from his life in California, he is fur clad, with precisely lined eyes and penciled brows, a wide smile and perfectly pressed and curled shiny black hair styled like Jackie Wilson, his dark skin shimmering off the light. I remember stories about Aretha Franklin’s backup singers, whose hair he styled, and the general milieu he found himself in, young, black, and creative—within reach of the stars of the day like Michael Jackson and Luther Vandross. He traveled with a gaggle of similarly fabulous women friends. I remember Carolyn most of all. She came home with him a few times and they laughed a lot in uproarious sinister sounding cackles. I burned to know their inside jokes and language.

“Baldwin mined territory that my mother knew: blackness, being born poor, the church, the cruelty of men.”

Uncle Frank was two years older than my mother, and he had come to live in my grandmother’s house when his mother went to Chicago for a better job in the late 1950s. I can imagine that my mother needed the company. They went to a black high school in North Memphis named after Frederick Douglass. He sang solos and gave dance performances at assemblies. In my grandmother’s shabby shotgun house, he was given his own room and he was always reading, creating something, or sneaking in young men from around the neighborhood through the back door.

My mother found a copy of Giovanni’s Room in Uncle Frank’s bedroom a few years after he had graduated high school and moved away. Published in 1956, the novel tells the story of David, a gay American man living in Paris, through an unflinching look at his romantic relationships with men. My mother was enraptured by the book and made a serious effort to find everything she could by its author, James Baldwin. She loved how he wrote plainly and personally, yet with eloquent urgency, as if the stakes were our very souls, our mortality on the line. He mined territory that she knew: blackness, being born poor, the church, the cruelty of men.

The author’s mother.

The author’s mother.

As a teenager, my mother was short and curvy with a narrow waist and sad black eyes that had a wry glint. She was a careful, diligent student who graduated from high school in 1962 as salutatorian of her class. Since she was a small child, she had written mysteries and won a contest in the eighth grade for a short story called “The Killer Who Killed Too Much.”

She didn’t know then that she was an artist, or that black people made books. The tattered textbooks she read from in school had been handed down from Humes High, a white school across town, Elvis’s alma mater. They read nothing by black authors. Her discovery of Baldwin early in adulthood awakened something dormant and sent her on a search for more in libraries, through girlfriends from work or church.

In my earliest memories, titles by Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and James Baldwin fill a bookshelf in our house that is tall and wide, a full wall in our hallway.

*

In January 1988, a group of 48 black writers and critics, many of them women, including Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Paule Marshall, June Jordan, and Toni Cade Bambara, wrote an open letter in praise of Toni Morrison, outraged that she had not yet won a Pulitzer Prize and that Beloved had not won the previous year’s National Book Award. They published it in the New York Review of Books:

Despite the international stature of Toni Morrison, she has yet to receive the national recognition that her five major works of fiction entirely deserve: she has yet to receive the keystone honors of the National Book Award or the Pulitzer Prize.

The legitimate need for our own critical voice in relation to our own literature can no longer be denied. We, therefore, urgently affirm our rightful and positive authority in the realm of American letters and, in this prideful context, we do raise this tribute to the author of The Bluest Eye, Sula, Song of Solomon, Tar Baby and Beloved.

James Baldwin had lost his battle with stomach cancer just a month before the letter was published. Morrison eulogized her beloved Jimmy in the New York Times, thanking him for “making American English honest”—clean and clear enough for the beauty of blackness to be articulated. “You knew, didn’t you,” Morrison wrote, “how I needed your language and the mind that formed it?”

The authors of Morrison’s letter did not believe that Baldwin had received the recognition that he deserved in his lifetime. They did not want her to suffer the same fate.

Up to that point, the response to Morrison’s work in the mainstream press had been tepid. When New York Times critic Sara Blackburn reviewed Sula, a book about outlaw black women and female friendship, in 1973, she lamented, “Toni Morrison is far too talented to remain only a marvelous recorder of the black side of provincial American life.” Blackburn warned that Morrison would need to transcend the “unintentionally limiting classification ‘black woman writer’” to be considered important.

Jazz, the multi-voiced, time-traveling novel about murder and love in 1920s Harlem, written with an extreme and aesthetically black musicality, got a similar assessment.

I didn’t hate this book the way I did Beloved . . . the book is sort of a set of bluesy linguistic riffs on Renaissance Harlem, ping ponging backwards and forwards in time, and it does contain some beautiful passages of prose; but to what end? The Sears catalogue might sound pretty to some people if read aloud in French, but that doesn’t make it great literature.

The authors of Toni’s letter performed a loving act of insurrection that wrote Morrison into the canon, onto high school and college syllabi, and affirmed the validity of black subjectivity. The intervention allowed Morrison to be honored for her work; it kept the work alive and accessible to girls like me. It also ensured that she would not suffer the fate of geniuses from our past, like Phillis Wheatley, who died poor, of malnutrition in 18th-century Boston, or Zora Neale Hurston, who died poor in 20th-century Florida, with Their Eyes Were Watching God, her masterpiece, out of print, until Alice Walker reclaimed her.

*

White Station High School is about ten miles east of Springdale. Alan Lightman, a physicist on MIT’s faculty and Kathy Bates, an Oscar-winning actress, are notable alums. The school’s lawn is neat and bright green; its newly renovated gymnasium takes up half a city block. The classrooms hum year round with cool air conditioning and up-to-date audio visual equipment. The couple whose children my Auntie had helped raise in the 1960s and 70s own an antique store in the neighborhood and live in a two-story colonial nearby.

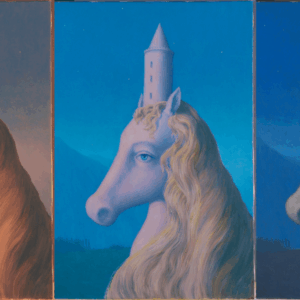

In 1995, two years after Toni Morrison finally won her Nobel Prize, I entered ninth grade there. By the next year, I was one of two black students in a Pre-AP English class. For our first essay assignment Ms. Leigh, a tiny, young-looking brunette with a pixie cut and round, black wire-framed glasses, gave us of 20 works of fiction to choose from and Song of Solomon and Their Eyes Were Watching God were on the list. I had read neither, but knew them from my mother. Ambitious, I decided to read both and to write about the one that resonated with me most.

Reading Their Eyes Were Watching God for the first time at 15 felt like someone was speaking directly to me. When Janie Crawford kisses her first crush, her grandmother forces her to get married. I put the book down then because the moment spoke straight to my heart, newly awakened to the complications of crushes and tumultuous high school friendships and perplexed by the dynamics of my own family. Hurston writes, “Nanny’s words made Janie’s kiss across the gatepost seem like a manure pile after a rain.” My breasts, my period, my crushes and first dates and nights with friends, any evidence of my burgeoning womanhood seemed to give my mother a dreadful, mystifying paranoia. We fought like hell with tears and screaming and, once, a gun.

“Hanging with her will get you pregnant,” she said to me inexplicably, years before I was having sex, about my best friend, Indira, who taught me to put on black eyeliner in the bathroom of our church basement. “The Devil’s in you,” she said when I talked back. “The phone is your god,” when I spoke to friends late into the night on weekends.

I wrote my first formal five-paragraph essay about Their Eyes Were Watching God, and I looked up to Janie Crawford. Beneatha Younger from Raisin in the Sun, Esther Greenwood from The Bell Jar, Sense and Sensibility’s Marianne Dashwood similarly spoke to me across time and gave me solace. They were intrepid heroines who owned themselves and fought for their own joy, despite the talk of neighbors, the confines of class and gender, the circumstances of their birth.

*

From stories my Auntie told me and scraps of handwritten birth certificates, I have been able to piece together that my grandmother left sharecropping behind in a Delta town outside of Clarksdale, Mississippi to come to the city, to Memphis, 75 miles north on Highway 61, for better work in 1927, the year of some of the Mississippi River’s worst flooding. Her own mother had been born in 1865, the year of emancipation, somewhere in Alabama, and moved to Mississippi with her husband for the chance to plant in the fertile Delta soil.

Unlike her forebears, my mother’s life was not marked by leaving as much as staying where she was, gathering material and planting seeds. If the freedom of the women in my family has been a long, multigenerational relay race, my mother ran a leg that allowed her children to leave, to take off in wildly different directions.

My brother ran the black Chamber of Commerce in St. Louis; my sister ran a startup in Silicon Valley. I ran to New York. More than a decade after I had been living and working there, I met Nigerian-American OlaRonke Akinmowo, the founder of the Free Black Women’s Library, in her brownstone apartment in Bed Stuy, on a cool and sunny March afternoon. Her apartment was about two blocks from my own. She came downstairs to fetch me, (“No bell,” she texted) while sneezing and talking in a groggy, nasally voice. She was suffering through a cold, and I mentioned how glad I was that she still agreed to meet with me. I wanted to interview her for an essay I agreed to write about the library for a black arts website.

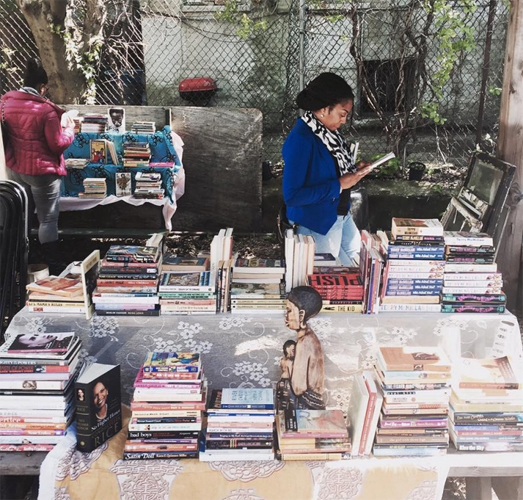

The Free Black Women’s Library is a mobile collection of more than 650 books written by black women that shows monthly at museums and studios and outside bars around Brooklyn, but also sometimes in Harlem and other nearby cities. Visitors can make donations or exchanges of books from all genres—children’s, YA, science fiction poetry, literary fiction—the only requirement is that the book’s author must be a black woman.

The Free Black Women’s Library (via NURTUREart).

The Free Black Women’s Library (via NURTUREart).

Like mine, Akinmowo’s apartment was filled to the brim with books. They were in actual bookshelves, makeshift bookshelves on window ledges and dressers, packed in boxes strewn across the floor. The library’s entire collection was stored there when Ola was not exhibiting.

Despite this seeming disorder, Ola could list off critical details about her collection. “Toni Morrison is the queen of the library,” she said. “She has her own special section. And we have more copies of Beloved than anything else.” Next most numerous are books by Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, Jamaica Kincaid, and Ntozake Shange. Every book donated had “Free Black Women’s Library” stamped on its inside cover, and volunteers counted the number of visitors at each event.

I arrived with three titles to contribute from my own collection: Into the Go-Slow, by Bridgett Davis, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie, by Ayana Mathis, and Harlem is Nowhere, by Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts. All written within the last five years, by authors that live or lived within the five boroughs, starring female protagonists who leave their homes and families of origin in order to create themselves.

The library has a large following on Facebook, with photos of guests, mostly black women, holding books uploaded during and after every exhibition. Some women pose alone, smiling vibrantly, and are of varying ages and gender expressions. Some photograph with their friends. The books are the focal point of each shot—the names of Morrison, Adiche, hooks, and Walker, prominent on their covers, at the center of each frame.

The literary labor of women like Akinmowo, Glory Edim of the Well-Read Black Girl book club, and Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts of Blacknuss builds on the work of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the tradition of black women’s clubs and literary societies from the 1890s that organized for social and political reform during the precarious years after the Civil War. Lynchings were rampant in the south, Jim Crow was in its infancy, and in the American imagination, black women were hypersexual, bestial, incapable of being raped. Black women’s societies encouraged temperance, service, and literacy to counteract this dangerous, miscategorization of black women that Melissa Harris-Perry calls the “crooked room.”

“Black women’s literature has filled in the crudely drawn lines of the dominant culture, correcting narratives that have defamed us, breathing depth and complexity into stilted stereotypes, creating space for us to see ourselves, to stand up, to expand.”

Of course, the ambient noise of racism and sexism persists. But the work of women like Akinmowo has cultivated an audience for literature by black women, and by creating vital spaces for community, it has allowed the work to reach the audiences who need it. Black women’s literature has filled in the crudely drawn lines of the dominant culture, correcting narratives that have defamed us, breathing depth and complexity into stilted stereotypes, creating space for us to see ourselves, to stand up, to expand.

We owe a debt to de facto librarians too, like my mother, who sat me at the kitchen table with a tape recorder while I memorized Easter speeches for church and poems for school, and my Uncle Frank, who brought the gift of James Baldwin’s clear prose to my family. They were writers without pens, painters who drew possibility out of thin, desolate air, culture workers who knew without knowing that creativity and language and learning were love and could be life itself.

These days, my mother lives alone in St. Louis and reads a few mystery novels a week. Sometimes she paints landscapes with acrylics. We talk often, about her grandchildren, my nieces and nephews, and always about books.

The last time I visited the Free Black Women’s Library, late last summer at Brooklyn’s Afropunk Festival, where the collection filled a booth on activism row, my sister and 17-year-old niece were in tow. I found Akinmowo, and we exchanged pleasantries. Her 14-year-old daughter was showing the guests around, prattling off facts about how the library worked, and naming all of the authors and books exhibited. I wished then for a time or space where black women did not have to go underground, to tirelessly innovate across generations correcting things in order to find some semblance of freedom. But until then, watching Akinmowo’s daughter, I knew that we would go on.

Feature image: detail from Patricia Watwood’s portrait of Ida B. Wells, © Harvard University Portrait Collection, Commissioned by the Kennedy School of Government.

Danielle Jackson

Danielle A. Jackson is a Memphis-born writer of essays and fiction living and working in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Velamag, The Rumpus, Blackberry, and Mosaic.