Life During a Post-Policy Presidency

Steve Benen on Donald Trump's Distaste for Governance

Despite his status as the first major-party presidential nominee in American history to have literally no experience in public service of any kind, Donald Trump was aggressively hostile to the very idea of a campaign shaped by the substance of governing and equally indifferent to learning how his own government works. His candidacy effectively served as a capstone, years in the making: a post-policy party would be led by a post-policy leader.

When Trump won anyway, his electoral incentive to be more responsible disappeared, but his governmental incentive intensified in ways he struggled to understand. Indeed, during Trump’s presidential transition process—a brutal obstacle course for even the most experienced and knowledgeable of politicians—there was an expectation that the Republican would shift his attention to the arduous task of assembling an executive-branch team. The president-elect defied those expectations, instead launching a first-of-its-kind postelection tour, featuring self-indulgent, campaign-style rallies in nine red-state locales.

It was an unmistakable signal that Trump, after having ignored the importance of policy making as a candidate for a year and a half, would not change. No president-elect has time for a multi-state tour during a short transition process, but the Republican made it a priority. Given a choice between grueling preparations and basking in the applause of followers, Trump had little trouble choosing the more entertaining and less substantive option.

As the tour got under way, the New Republic’s Alex Shephard noted, “Donald Trump, a man who has a very short attention span and requires instant gratification more or less constantly, loves campaigning because he has a very short attention span and requires instant gratification more or less constantly.” What the incoming president did not love was getting up to speed, preparing for the profoundly difficult job he’d sought despite knowing very little about what it entailed.

As the new administration slowly took shape, it stood to reason that Trump would surround himself with more qualified personnel whose expertise he could lean on after Inauguration Day. But between Thanksgiving and Christmas 2016, as new cabinet nominees were announced, many of the choices were as inexperienced as their new boss. Most of the incoming Trump cabinet had no governing experience, no experience in the subject area they’d oversee, no experience managing a large agency, or some combination thereof.

In a dynamic that mirrored the Republican’s pre-election operation, Trump had staffers whose job it had been to prepare governing plans, but as the political website Politico reported in early December 2016, Trump and his inner circle “largely ignored those plans.” The article added that policy experts, eager to assist the incoming White House team, found it difficult to get the attention of the president-elect and those in his immediate orbit.

The only thing that seemed to capture and keep Trump’s attention during the transition process was the degree to which NBC’s sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live made him the butt of jokes.

Trump’s post-policy posture broke new ground: he struggled because, in a rather literal sense, he had no idea what he was doing or what he was talking about.By Inauguration Day, Trump and his team were so unprepared for the transition of power that they were reduced to asking several dozen senior Obama administration appointees to remain in their jobs, not because Republican officials approved of their work, but because the incoming administration wasn’t yet properly equipped. The services of Obama’s people were required for the continuity of governmental operations.

This included, among others, positions related directly to national security. On January 18, 2017, Foreign Policy magazine reported that Trump was poised to enter the White House “with most national security positions still vacant, after a disorganized transition that has stunned and disheartened career government officials.”

One career government official told the magazine, “I’ve never seen anything like this.” That was because no one had ever seen a post-policy administration try to fill important governmental posts before.

Once Trump tried to govern from his position of policy passivity, his ignorance served as a near-constant hindrance. Not only was the president unable to persuade people to support proposals he knew nothing about—during the health care fight(s), the Republican routinely found it difficult to talk about his party’s plans in complete sentences—but also Trump’s vision, such as it was, became a black box that no one, including his ostensible allies, could understand.

As Trump’s presidency flailed, National Review magazine’s Rich Lowry, a conservative sympathetic to the Republican’s cause, reported, “No officeholder in Washington seems to understand President Donald Trump’s populism or have a cogent theory of how to effect it in practice, including the president himself. … Trump, for his part, has lacked the knowledge, focus, or interest to translate his populism into legislative form.”

History offers a long list of American presidents who failed to advance their priorities for a variety of reasons. Some couldn’t persuade lawmakers to follow their lead. Others presented ideas that crumbled under scrutiny. Some saw their agendas overcome by scandal.

“I thought it would be easier,” Trump complained in 2017, referring to his months-old presidency.But Trump’s post-policy posture broke new ground: he struggled because, in a rather literal sense, he had no idea what he was doing or what he was talking about. As Brian Beutler summarized in the New Republic around the president’s hundred-day mark, “Trump has failed because he has little in the way of clear substantive objectives or strategies to meet them, and he lacks the interest in or knowledge of policy and process that he’d need to correct course. Even if he had a good ear for sound advice, and the patience required to follow it, he is surrounded by amateurs and opportunists who send him endlessly careening between contradictory goals and various tactical dead ends.”

In April 2017 the New York Times featured twenty people who served as close Trump confidants outside the West Wing. Seventeen of them had no governing experience at any level. For an amateur president unfamiliar with the basics of policy making, and little interest in learning, it was hardly ideal.

The result was a president who assumed governing would be simple and who seemed baffled to discover it wasn’t. “I thought it would be easier,” Trump complained in 2017, referring to his months-old presidency.

It was among the most believable concessions he’d ever made. Trump launched his bid for national office working from the assumption that there were straightforward solutions to every possible challenge, and every president had the capacity to accomplish great things through a combination of decisiveness and force of will. The only reason other presidents failed to follow this path to governing success was because, as far as Trump was concerned, they were all idiots. It was this foolhardy vision that led Trump to assure voters that he could “make possible every dream you’ve ever dreamed” and “fulfill every single wish” Americans have.

By all appearances, the Republican’s audacity was entirely sincere. He was convinced that he could take office, bring affordable and high-quality health care benefits to everyone, cut taxes, defeat our enemies, create record economic growth, fix an immigration mess, strike a peace agreement between Israelis and Palestinians, negotiate new trade deals, and eliminate the national debt—quickly and with relative ease—because the only thing standing between the United States and historic greatness was a bold leader like him who could simply bark orders and deliver results.

In reality, Trump did not know what he did not know. The nation’s first amateur chief executive sought the presidency first, then got elected, and then went about trying to learn what he was supposed to do with his awesome power—so long as it didn’t require too much effort or interfere too much with his television-watching habits.

It was a recipe for failure for a president who found it easier to guess than to govern. Trump has replaced the traditional model of policy making with whims and impulses. After nearly two years in office, the president went so far as to boast, as if he were a real-life inspiration for Stephen Colbert’s overtly buffoonish Comedy Central character, “I have a gut, and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.”

It was post-policy thinking at its most transparent.

When Trump tried to take data and evidence seriously, he proved himself unable to tell the difference between metrics that matter and those that don’t. Well into his presidency’s third year, the website Politico reported on an Oval Office meeting in which several members of Congress lobbied Trump not to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria,a shift he’d been considering, despite the advice of his administration’s national security team. The president ordered Dan Scavino, the White House’s social-media guru, to join the conversation.

When Scavino, who had helped manage one of Trump’s golf clubs before joining his boss’s political operation, arrived at the meeting, the president directed his aide, “Tell them how popular my policy is.” It fell to Scavino to brief the lawmakers in attendance on the online reactions to Trump’s social-media content related to withdrawal from Syria.

In the process, the president made clear that when it came to deciding the smartest course in complex policy challenges, the kind of evidence that influenced him was retweet tallies—hardly the characteristic of a leader who’s come to terms with the seriousness of governing a twenty-first-century global superpower.

When Obama asked Republicans five years earlier to produce “empirical data” to justify their positions, this was clearly not what the Democratic president had in mind.

At times Trump took his post-policy approach to government to otherworldly heights. In March 2018 the Republican ignored the judgments of his team and expressed public support for the creation of a militarized Space Force. Describing a conversation with White House staff, Trump explained, “You know, I was saying it the other day, because we are doing a tremendous amount of work in space. I said, ‘Maybe we need a new force. We’ll call it Space Force. And I was not really serious. Then I said, ‘What a great idea. Maybe we’ll have to do that.’”

How would this differ from the existing Air Force Space Command, which was already responsible for space operations involving missile detection and satellite coordination? Why had the Trump White House balked after some in Congress proposed the creation of a US Space Corps? How would a militarized Space Force overcome the restrictions created by the Outer Space Treaty, which the United States signed in 1967 and requires all signatories to use “celestial bodies” exclusively for “peaceful purposes”? The president didn’t have answers to any of these questions—and by all appearances, he couldn’t have cared less. The last thing Trump wanted to hear about were annoying questions about governing details that might get in the way of his fun.

By his own telling, the Space Force started as an offhand joke. Nevertheless, three months later, Trump directed the Pentagon to create a new branch of the US military to turn his joke into reality—not to serve a specific policy purpose or to address a shortcoming in the existing military structure, but because the president saw totemic value in promoting something he thought sounded cool. Soon after, the White House sought $8 billion from Congress in order to pursue the dream the president stumbled onto by accident.

That money was expected to come from American taxpayers, but it wasn’t the only source of revenue on the minds of the president and his team: By August 2018, Trump’s reelection campaign was sending fund-raising appeals to supporters, asking them to vote on their choice for a Space Force logo. (One of the less creative alternatives was nearly identical to the official logo of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA, but in a different color. In January 2020, the agency unveiled its official choice, which looked eerily similar to the logo from the Star Trek franchise.)

It captured the president’s ridiculous approach to governance: start with an unexamined joke, transition to executive directives sorely lacking in purpose or meaningful scrutiny, and end with a hashtag-ready phrase that far-right voters could chant and grab their wallets to support.

At one point, after a Thursday morning round of golf in 2018, Trump published a random tweet that read, “Space Force all the way!” The Atlantic’s David Graham compared the president’s substance-free idea to one of his most notorious and duplicitous scams: “Anyone tempted to get excited about the Space Force would be well advised to keep the Trump University precedent in mind,” Graham wrote. “The seminars were a short-term success: Thousands of people signed up, creating a new revenue stream for Trump. But they eventually wised up that they weren’t buying real-estate secrets so much as a bill of goods, and some of them sued him, resulting in a $25 million settlement. Eventually, misleading branding schemes have a tendency to fall back down to Earth.”

None of this bothered the president. In fact, he didn’t even try to push back against the criticisms. Trump was too busy promoting an idea that he thought made him look forward-thinking—and using it to pry donations from his followers. He was content to leave governing details to members of governing parties.

It’s easy to imagine rank-and-file GOP voters finding the post-policy critique insulting, but Republicans should be far more offended by their party than by the unflattering assessment. For those who sincerely believe in the party’s stated principles, it does them no favors to elect policy makers who generally share the same vision but who ultimately don’t care enough about governing to competently shape legislation or to implement conservative policies effectively once they’ve passed.

In other words, no one benefits from a two-party system in which one of the two no longer cares about governing responsibly. In order to recover from our stagnant status quo, Republicans will need to overcome their post-policy problem, currently affecting every area of Americans’ political lives, and reclaim its status as a party capable of mature policy making.

A governing party recognizes the importance of rigorous policy making. It evaluates evidence before and after trying to implement ideas. It starts with a question and works toward an answer, rather than the other way around. It is swayed by reason, data, and a clear sense of how best to use governmental levers of power. Over the last decade, the Republican Party has failed spectacularly on each of these fronts in every major dispute of the era.

This book is not a comprehensive recitation of American politics since Barack Obama’s 2008 election. Rather, it’s intended as a lens through which to see political developments and an argument about the importance of its effects. After all, the art of governing and effective policy making has inherent value. Those who see serious national challenges need to be able to turn to competent public servants who are willing and able to craft and implement sensible solutions. The alternative is a system in which officials abandon their governing responsibilities, problems go unaddressed, and the public suffers from the rot.

The book is also constructed as an issue-by-issue indictment, shining a light on the defining political fights of the day, each of which featured a Republican Party that simply wasn’t up to the task of governing.

It’s not enough to conclude that politics in the United States is badly broken; if the system is going to recover, it is necessary to understand why. And while the problem is no doubt multifaceted, at its heart, ours is a political landscape featuring a governing party vying for power against a rival that’s abandoned the pretense that public policy matters at all, creating an untenable model that’s eroding the American policy-making process and failing to serve the public’s interests.

The Republican Party has not always been a post-policy party, and it need not remain one indefinitely. The vital challenge facing the GOP and the civil polity at large is coming to terms with the party’s collapse as a governing entity and considering what the party can do to find its policy-making footing anew.

____________________________________

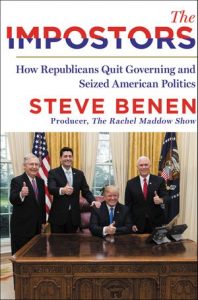

From The Impostors: How Republicans Quit Governing and Seized American Politics by Steve Benen. Copyright © 2020 by Steve Benen. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.