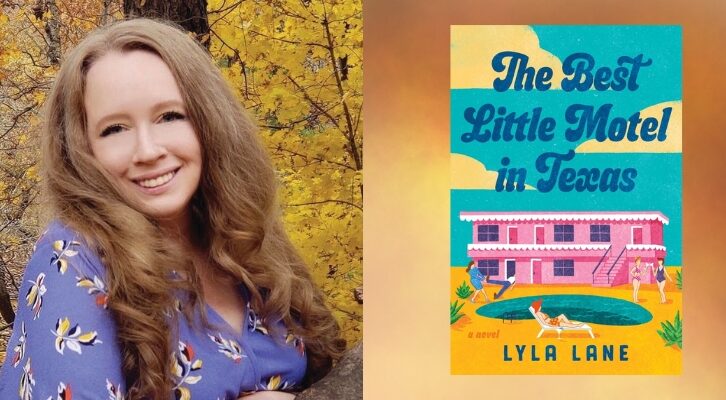

Liana Finck on How to Write Like a Cartoonist

"There is no such thing as skimming the surface."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

A single-panel cartoon is a joke in drawing form: you start with a set-up, then add a punchline. The set-up has to be something most of your readers will recognize, so that they’ll get the joke. Here are some that New Yorker cartoonists rely on often: desert island, cocktail party, therapist’s couch. A set-up often contains a twist: there is a dog at the cocktail party, or the person stranded on the desert island is wearing skis. Choosing the set-up is the hard part. Once you have your set-up in place, you can forget about structure and be purely creative. I’ve always wondered if it was possible to make a longer project more like a cartoon or joke. I thought that if only I could find a really expansive set-up, it would carry me along and keep me from falling into the horrific questions real novelists and graphic novelists have to ask themselves, such as What am I doing? and Why? I’d be able to let the premade structure do the heavy lifting of storytelling and focus on making my fun little jokes.

For my latest book, I decided to test out this theory. I️ chose the Book of Genesis as a set-up. Everyone has heard of it; some know it well. It’s certainly holy, and therefore it’s vulnerable to being made fun of. As a personal twist, I decided to make my God female. I figured that would cause a continuous parade of interesting questions to arise in the story. A woman artist (and God is an artist) is seen differently from a male artist. A woman’s anger is read differently from a man’s. A female God promising the world to a male believer might be interpreted as an overbearing mother or pathetically lovesick schoolgirl as opposed to a strong paternal force. Even though I was raised with religion (Judaism), it had never really occurred to me to wonder if I believed in God. But the minute this character came to me, I knew I believed in her. Because she is me.

In my rush of confidence with this girl God character, I thought my lovingly undermining rendition of Genesis would just flow. And it did, at first. The problem was that my target wouldn’t sit still. I️ realized I️ didn’t know the Old Testament (or Torah, as we call it) at all. It is a jumble of mysterious parts, some written centuries apart. I️ can’t summarize what it is trying to say. And what story does cohere, when you really look at it closely?

This, I think, is the difficulty of writing a book in general. You need to make something that can be seen at a distance as a coherent object and that a reader can enter as its own universe, full of stand-alone details. As a person who has trouble holding two ways of seeing in her mind at once, reading a book gives me the same kind of vertigo I get from trying to navigate using a map, or from contemplating my own mortality.

Even jokes and cartoons are complex stories with layers of history to them and multiple meanings.

I went to Hebrew Day Schools as a kid, so I have a lot of experience laughing at the God of the Torah. I used to draw him (sic) as a comically irate cloud. His big, id-like anger was delicious to me. I brought this energy to my book. My female God is not a woman. She’s a girl: innocent, full of big feelings, and bursting with creativity. The first part of the project — the stories of creation, Babel, and Noah, which feel (and are) very ancient, with their cosmic brevity — was a pleasure to work on. I highlighted the innocence of the story of creation as I see it: how joyful and funny it is to see the creation of Earth as an art project made by a child. The story of Noah went well, too. It’s a big story, full of big sadness and big joy, but expansively simple. The story is this: God loved a man but hated everyone else. She was moody. She destroyed the world. She saved him. She inadvertently traumatized the man in the process. This story, too, was fun to adapt.

What I came to think of as the second part of Genesis — the long, boring story of Abraham and the short, sad story of Isaac — was harder. The first was a story about the petty meanderings and real-estate dealings and possessions of a man named Abraham. He seems like a good person and strives to do well. He’s just a bit dense, sometimes unforgivably. The story of Abraham made me confront, in a way the stories of Creation and Noah did not, that the Torah and my religion is so steeped in the patriarchy that it isn’t exactly… mine. I solved Abraham by telling his story like a Philip Roth book: a good book that was not written for me, a book with blind spots that are more apparent to me than others. I made Abraham into a young, self-important writer or artist character who thinks of himself as a genius. Having heard the voice of God, he follows it single-mindedly all his life, as his life passes him by.

And after Abraham, well, the stories of Jacob and Joseph are my favorites. They’re sophisticated and arguably (a tough argument, but still!) somewhat feminist, full of twists and turns, like a great 19th-century novel. There was even less for me to make fun of in these stories than there was in Abraham. What did I do with them? My earnest best.

After realizing that I saw the book of Genesis as a story with three distinct parts, I became a structure person. I created an overriding, earnest scaffolding to make sense of the spliced-togetherness of the text. I decided to make the story of creation take place in the past, Abraham in the present, and Jacob and Joseph in the future. This was a big, sweeping move, and a lot of fun. It led me to have God age throughout my story. From a child, she becomes a teenager, then a woman. She loses her innocent self-centeredness, becomes introspective. As she grows up, she stops being a cartoonist and develops a taste for story.

And so did I.

Even jokes and cartoons are complex stories with layers of history to them and multiple meanings. There is no such thing as skimming the surface. There is only the marvelous illusion of doing so.

__________________________________

Let There Be Light: The Real Story of Her Creation by Liana Finck is available via Random House.

Liana Finck

Liana Finck is the author of Passing for Human and a regular contributor to The New Yorker. She is a recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, and a Six Points Fellowship for Emerging Jewish Artists. She has had artist residencies with MacDowell, Yaddo, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Center, Headlands Center for the Arts, and Willapa Bay.