Let the Kids Get Weird: The Adult Problem With Children’s Books

On Jon Klassen, Ruth Krauss, and the Grown-Up Weight of Nostalgia

Picture books must hitch a ride on the parent if a child is to get a look-in so the children’s publicity machine is tilted fully at the adults. The frontlist is built around celebrities children have never heard of (is Zadie Smith a sure thing for a young reader? Is Aubrey Plaza?), and market needs—ideas around the science of reading, social education, and moral values (of kindness, of bravery, of Christianity, etc.).

On top of that, picture books are, perhaps more so than other genres, subject to the aesthetic of bookishness—they are large format, hardcover decor, objects that parents like the idea or look of, tools that have been deemed “appropriate” or “necessary” for their kids.

“There’s this desire to raise them to be the best baby you can,” says Hayley DeRoche, an author and comedy writer who runs the popular Sad Beige Baby accounts on Instagram and TikTok satirizing the current minimalist, monochrome nursery trends. “Sometimes I think that optimization steamrolls the silliness of childhood, the cuteness of babyhood, in an attempt to adopt this aesthetic that’s much more adult.

People keep buying The Giving Tree, despite the fact that children hate the book.

The question, then, is how children get their hands on a book like The Skull, the newest from Jon Klassen and a goodie but—to emphasize—a book about a girl and a skull, friendship and death.

Adapted from a Tyrolean folktale, The Skull opens with Otilla running through a dark, textured forest chased by something unseen, and stumbling on a castle. A skull appears at a window and agrees to let her in if she will carry it. Inside, she picks a pear from a tree and shares it with the skull, who chews it gratefully before the morsel drops out the back of his head onto the floor. They become friends. Otilla trundles the skull about the castle in a wagon. The ingredients of a plot—a bottomless hole, a tall rampart—are introduced for Otilla and the skull to take on a headless skeleton who haunts the castle at night.

It’s the perfect story. Strange and with a logic all of its own. Annihilation is a possibility, but the story doesn’t bother with the abstraction of death. What is beyond the bottomless hole is nothing—we don’t think beyond the black circle.

This is not typical of most children’s books.

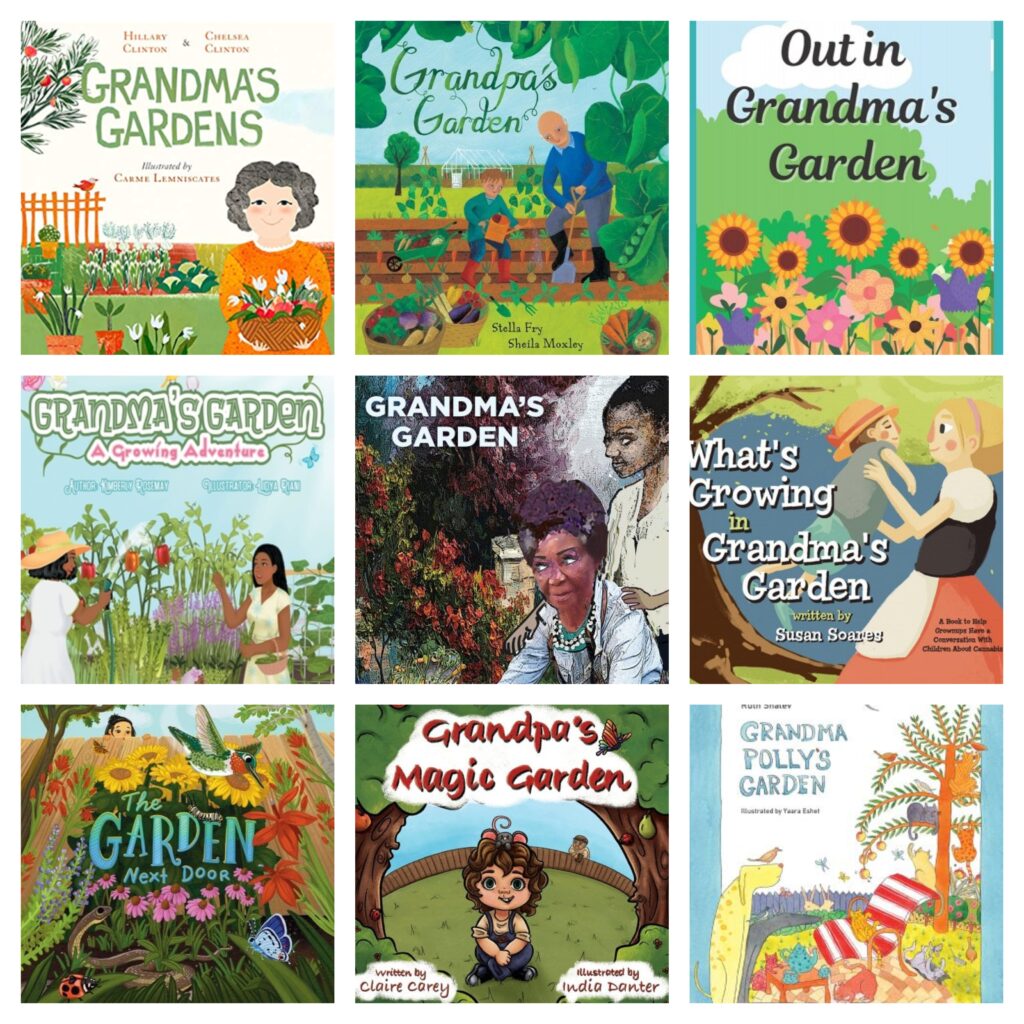

Walk your fingers along the children’s bookshelf at a store and you’ll see a nostalgic or abstract viewpoint that I’m not convinced children share. Take, for example, these books:

“One day you’ll die too, and you’ll become a garden bench.” The moral of many children’s books.

“One day you’ll die too, and you’ll become a garden bench.” The moral of many children’s books.

These are books for Grandma to buy and give her grandkid. The garden is a symbol for something: love, memories, history, possibility. Okay, but in a battle with Dragons Love Tacos, the child is always going to choose a dragon puking fire over something nebulously wistful about growing seedlings.

Ditto the realm of children’s books about trees:

I get it—trees are a thing that kids and adults have in common (also: benches). Kids climb them and adults like to … look at them, I guess. We adults can’t stop writing and publishing books like this. And since there is no real critique of children’s books (since any children’s book author or illustrator is assumed to be trying to do something nice for kids, and don’t knock it), we keep making more of them—the kids haven’t told us otherwise. As The Gruffalo author Julia Donaldson put it in a radio interview, “When you read an adult novel there’s always about three pages of reviews.”

For kids’ books, there are none.

*

In 1975, Ursula Le Guin published a paper, “The Child and the Shadow,” that addresses children’s capacity for darkness within themselves and the function of fantasy stories. One of her main points was that while critics often read fantasy in terms of good versus evil, these forces are really opposite instincts, parts of a single character split in two—Gollum and Smeagol, the Elves and the Orcs.

And kids are less tainted by the psychic effects of this darkness, she said, quoting Jolande Jacobi: “A child has no real shadow, but his shadow becomes more pronounced as his ego grows in stability and range.”

We reckon with our shadows in middle-age, according to the literature of psychoanalysis, a time when we may find ourselves ensconced in the children’s literature scene. Picture a middle-aged author wrestling their own existential fear of death while writing a bedtime story about bunnies: Writing good children’s fiction as an adult is hard.

“It’s hard not to get entangled in the collective consciousness, in simplistic moralism, in projections of various kinds, so that you end up with your baddies and goodies all over again,” wrote Le Guin. We toggle between confronting children with the reality of the world (note the bleak realm of climate fiction for young readers) and with blanketing them in fluffy chickens.

“The young creature does need projection. But it also needs the truth,” LeGuin wrote. (For a deft look at mortality, go to Wolf Elbruch’s Duck, Death and The Tulip, in which Death is a character.)

“People in publishing often talk about ‘child-friendly’ books, which suggests something consoling, sweet and kind of nostalgic. But that’s a smokescreen, because those qualities attract parents and teachers more than children,” says Natalia O’Hara, author of Hortense and the Shadow and other books with her sister, illustrator Lauren O’Hara (of the forthcoming Madame Badobedah and the Old Bones). “Children like sweet and safe stories but they also like dark, bleak, unsettling or horrible stories. Children are like everyone else, they want stories that reflect the whole contradictory tangle of their lives.”

For children I know, that truth encompasses sometimes wishing your sibling didn’t exist, and seeing the world in happy stripes of orange in the morning and daggers of blue at night when it’s late and there has been too much day.

These uncategorized feelings animate many of Klassen’s characters, several of whom eat or murder other characters; plot points that did not preclude a Caldecott Medal. Klassen is by no means the only inventive children’s book author or illustrator out there now (I love books from Mac Barnett, Oge Mora, Dan Santat, Adam Rubin, the Fan Brothers, Carson Ellis, Molly Idle, Julia Donaldson, and Sophie Blackall, to name just a few), but he’s a useful shorthand for what children’s books can be, at a time when derivative and sanitized books keep peeling off the production line.

The Instagram account @pipesinkidlit is run by a former publishing insider whom we’ll call Pipes, and curates the bygone days of dandy-looking picture book characters puffing away on corncob pipes—Richard Scarry illustrations pop up more than once along with different iterations of Santa Claus, the Frances books, and forgotten characters like Detective McSmogg.

“I feel like pipes, nowadays, are one small metaphor for a bigger idea: that children’s books should not be completely safe,” says Pipes. “I don’t want my kids to smoke, or to think smoking is a fun or a cute activity. But I also don’t want picture books to be these little zones where everything is perfect.”

That is, the urge for publishers to avoid pipes—or anything else that might depress sales—has led Pipes to appreciate writers and illustrators who take risks. “The best children’s books, for me, start conversations or inspire some thinking—and typically that doesn’t happen with simplistic morals, or with books that model idealized experiences. When I see a pipe in children’s books today, I feel like the artist and author made a decision to go against the grain, perhaps hoping that the reader will take a moment to talk with the listener about what’s on the page.”

That might mean we get fewer truly weird or unsettling stories.

Overly sanitized stories mostly risk being forgettable, according to Pipes. “When you look back at the past, you can cherry pick the great books that took risks, said something original, and stood the test of time. But in any era, there were far more books that were boring, or dumbed down, or preachy, or sappy. Those are the books that, for the most part, are forgotten and go out of print.”

*

Klassen has given a hat tip to the work of Ruth Krauss, who collaborated with Maurice Sendak on multiple books, and whose 1981 book Minestrone is out of print but can be viewed online. In the story?—poem?—HOW TO WRITE A BOOK, Krauss writes:

You can write books about anything … You could write a book for someone who can read only one word. You could draw a horse on the first page and write HELLO, and the second page could be a bear and write HELLO, and the third page could be a kitten and write HELLO, and the fourth could be a monkey and write HELLO, until as many as you want. At the end maybe you could write GOODBYE, just for fun.

If you want to dip a toe into post-structuralism, each of her stories destabilize the boring and hegemonic dynamic of parent and child, reader and book.

Here’s the story “QUESTION or maybe ANSWER”:

in a cottage kitchen

CHILD: Mother, was a skyscraper

once a little cottage

like ours?

MOTHER: No, dear. Of course not.

(the COTTAGE begins to grow …

We know days are 24 hours long and repeat the same beats. But in Krauss’s literature, cottages can grow, and it’s a nice day right before THE SUN falls down on the ground.

There’s an inventiveness that sprouts from the alternate reality children live in. My son is constantly wrong about things: “This is a bag of sand,” he said, slapping a large bag of soil at a garden center with satisfaction. “A baby deer!” he shouted, pointing over the road at a rabbit frozen in fear in the neighbor’s yard. I think that if I was hit by a truck tomorrow, he would have trouble sitting still at my funeral. Something would distract him, he’d start giggling, go boneless, demand fruit gummies. Because a funeral is an adult idea about how to recognize death. In kindergarten, you’re still learning all the faces. A lot is still beyond language.

So, to speak to a young audience the children’s author needs to find a way to beat back their own adultness. To paraphrase Catherine Lacey quoting Rachel Cusk, “Can an [adult]—however virtuosic and talented, however disciplined—ever attain a fundamental freedom from the fact of his own [adulthood]?”

“I don’t think you ever can,” says O’Hara. “But being an adult talking to a child doesn’t mean babbling sweet-talk about happy bunnies. You can just be a human talking to another human. You can kind of say, ‘This is something I’ve noticed about life, what do you think?’”

Here’s a bit more Krauss:

PLAY 1

NARRATOR: in a poem you make your point with pineapples

PINEAPPLES fly onto the sage from all directions

SPY: and it would be nice to have a spy going in and out

*

There’s something to be said for the vibe of the thing, at a time when children’s books are being highly engineered (remember that an early childhood educator had a hand in The Teletubbies). It’s less about zeroing in on the magic formula, and more about feeling your way through a manuscript.

When Terry Gross called out a line from Bumble-ardy in a 2011 Fresh Air interview (“I won’t ever turn 10”), Maurice Sendak told her: “It touches me deeply but I won’t pretend that I know exactly what it means. I only know it touches me deeply, and when I thought of it, I was so happy I thought of it. It came to me, which is what the creative act is all about. Things come to you without you necessarily knowing what they mean.”

The story on which Klassen based The Skull had a different ending, he explains in the author’s note. He found it in an Alaskan library while doing a storytime event, and when a librarian helped him get his hands on a copy again a year later, found he had misremembered the plot:

This is a very interesting thing that our brains do to stories. If you read this book once and put it back on the shelf, and a year from now someone asks you how this story went, the same thing will happen: your brain will change it. You will tell them a story that is a little different, maybe in a way your brain likes better.

This kicks a real hole in the idea that children’s books should be or are prescriptive, and thus need to be regulated by vigilantes at public library storytime. It also explains the heavy-handed writing in books like Kirk Cameron’s As You Grow (about a tree) and Charlotte Pence’s Marlon Bundo’s Day in the Life of the Vice President (about a bunny). Once you attune your eyes to the adult baggage, you can see stories sagging under its weight everywhere.

“So much of parenting is really acknowledging how much we think we know and then facing how little we know, says DeRoche.

Writing a children’s book will always be an imperfect exercise, since we’ve already left that land.

THE SUN crashes to the ground.

end.

Editor’s note: An earlier version incorrectly identified the author and title of Marlon Bundo. It has been updated.

Janet Manley

Janet Manley is a contributing editor at Literary Hub, and a very serious mind indeed. Get her newsletter here.