Learning About the Natural World (Inside My Family’s Cult)

“Mother doesn’t believe in protecting children from anything.”

I look out at the nearly full moon, and its reflection on the snow is so bright that through the big window, I can see the sleeping faces of my sisters, their hands under their cheeks, looking like they’re righteous.

Mother moves on to “Are You Washed in the Blood,” and I picture a red snow plant, peeking its head up in the spring. She has been preparing these songs for the past couple of nights, because she always plays her violin at Grandpa’s Christmas Eve Communion ceremony.

Grandma used to accompany her on the piano, before she had her stroke. Mother and Grandma would play hymns while Grandpa gave us the body and blood of Christ. Grandpa always takes his time, touching the forehead of each of his followers, whispering and chanting to each one of them, so Mother has to have a lot of hymns prepared.

When I was little, Grandma taught me to sing soprano while she sang alto. She taught me to play all the major keys on the piano, and we were starting to make the shifts back and forth through minor, augmented, and diminished.

Since her stroke, I’ve been wanting to teach them back to her, but we don’t get to see her very often, now that we live on the Mountain. “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” I move my fingers, like I’m playing the piano on my sleeping bag. “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.” “Bringing In the Sheaves.” My fingers curl to play the chords. “Amazing Grace.” “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.”

The night in our bunks is cold, and although we shiver, we are full of hope. Mother’s music sounds like singing. She doesn’t like when I make comparisons like that. If I told her the violin sounds like a voice, she would tell me I’m fabricating. She says fabricating is a sin, so now I do it only in my head.

Now her violin sounds like a duet with dissonance. I have to remember to write that down in the margins of the Sears catalog, where I’ve started keeping all my favorite lines, going back to them over and over when no one is looking.

“The man in the moon is watching us, Danny,” I whisper, knowing the sound of the music will muffle my words. My brother’s face is glowing from the moonlight, and he looks over at me with droopy eyes, like he’s been ordered to nod off but refuses.

“Is that God?” he asks. “Is that where God lives? Or Santa Claus?”

“God lives in heaven,” I say. “Santa lives at the North Pole.”

“Is the North Pole on earth or in heaven?

“The North Pole is where the magic happens on earth. God saves his magic for after we die.”

“I don’t want you to die.”

I look at Danny with maternal confidence, like I know what I’m talking about. “Santa won’t let me die tonight. But if I do, if I die before you, I will ask God to make sure Santa takes extra good care of you.”

“Lights out,” our father barks, and darkness descends as if from the hand of God.

*

We wake up. Underneath the stockings are four suitcases: yellow for Lizbeth, pink for me, blue for Becca, and brown for Danny. We will live out of these suitcases for the next ten years.

*

FIELD NOTE #3 Yucca

Yucca is a shrublike plant with a single stem or a few short stems surrounded by narrow stiff leaves at the expanded base. Its flowers, which each have three petals, grow on a central stalk. Its fruit, which follows the flower, is fleshy and approximately 6 or 7 inches long, resembling a short banana.

Commonly referred to as “our Lord’s candle,” yucca can be found on dry slopes from 3,000 to 6,000 feet elevation.

All parts of the yucca can be useful to humans, and as it matures throughout the year, different sections of the plant become edible. Prior to blooming, you can cut the flower stalk and cook it overnight to soften it. You can also eat the young flowers, though if you’re new to this, you’ll want to boil and purge the cooking water multiple times, to eliminate the sharp taste.

The fruits can be eaten raw or roasted. The seeds can be consumed whole or pounded into a paste. The heart of a yucca plant and the stalk of the flower spike can both be roasted or boiled on an open fire pit and eaten like squash.

*

Mother doesn’t like when we talk. But sometimes when we’re out on training trips, she tells us stories, and that’s almost like a conversation.

I like the intensity of training trips, even though it’s unclear what the end of the world we’re training for will look like. Unlike the Trip, these training trips are sporadic and unplanned, so I don’t get to look forward to them as much as I would like. I guess that is kind of the point, though. We should be ready for anything, for the day of the Lord will come as a thief in the night.

Sometimes we hike long distances on these training trips, and sometimes we ride in the back of the World War II–era Jeep that Dad picked up from government surplus. Mother says you have to go where you can to get what you need. Even when you don’t know where you’re going.

Today we take the Jeep, because we are collecting boulders to build an irrigation system. We head out to the high desert, about fifteen miles east on the 138, toward Mormon Rocks, a region in the Mojave Desert with a nearly endless supply of stones, some of which will be the sizes we need. Mother brings the transistor radio and a walkie-talkie, in case Ranger Harold from the Forest Service needs to reach her.

On this warm spring day, while we heave rocks into the back of the Jeep, Mother tells us that these sandstone formations should really be called Serrano Rocks, because the Serrano people lived here long before the Mormons came through. She says it’s a shame they don’t teach real history in the schools these days. “Many Native peoples lived in these caverns for thousands of years as hunter-gatherers. We just don’t know who they were.”

“How do we know about the Serrano?” I ask.

“Because they’re the most recent. We know they lived here for at least seven hundred years before the Mormons came through in the 1840s. There was a massacre here during Civil War times, although people don’t talk about that much. Can’t blame the desert Indians for not wanting to give up the last of what was theirs, can you? No one teaches you that in those useless public schools, but what happened here was its own civil war, between how people lived on this land for centuries and what the Europeans who came through mandated it become. In the mid-nineteenth century, the Mormons didn’t take favorably to the Serrano or to any of the Native tribes. I mean, they said they were okay with peaceful Indians, but who could be peaceful when someone comes in and takes away your way of life?”

Mother keeps lifting rocks this whole time while she’s talking, but even when she gets riled up, her breath stays steady.

“But you know they’re still here, the Indians,” she says. “Mostly on reservations, where white people can keep them under control.”

Mother knows a lot about things they don’t teach in school, and unlike Grandpa, she’s adamantly against keeping people confined.

“Your dad plays basketball with the Sherman Indians, you know, so you should ask him sometime what they say about all this.”

I look at her, not sure I’ve heard her correctly. I can’t imagine Dad talking about this. Dad doesn’t talk about anything except military training. I guess I don’t know what Dad does in the weeks and months he’s not with us. But whatever I’ve been imagining him doing has never included playing basketball with Indians—I can tell you that.

I file this information away to ponder later. All I can think about right now is how hungry I am. Were the Serrano hungry out here, when the only food they had was what the desert offered? The high desert is a tough place to forage, but Mother says everywhere on earth, there is life, so there is always sustenance if you know how to look for it.

Training in the desert prepares us for the trials and tribulations to come, which John predicted in Revelation through lots of symbols, many of which we’ve memorized, so we’ll have the muscle memory to respond effectively.

I think about the Mormons, and what they ate along the trail they carved here a century ago. Why did they come here? It couldn’t be because they wanted access to the Serranos’ food. It’s not easy living off the food you can find here. Most white people don’t have the patience for the work it takes to forage in regions they don’t understand. The Mormons must have brought their own beef jerky or cornmeal mush or salt-rising bread. There is no way they relied on yucca and prickly pear cacti, or getting water from distilling urine in a pit, like Mother taught us to do.

I look at the yucca, yellow and flowering and abundant across the landscape, which makes everything look like a fairyland. Mother says we are in luck. She says you’ll never go hungry in the spring out here.

She tells us, “Where there is color, there is nourishment. If you can see color, you have access to nature’s dance, and following her rhythm will help you find the bread crumbs you need to survive.”

When Mother talks about bread crumbs, she means metaphorically. We never pack food on these trips. We just eat what we find along the way, because Jesus said his disciples needed nothing when they went out to preach his word: no bag, no bread, no copper in their money belts.

Mother says most people boil yucca flowers before eating them, but when the petals are young and soft, you don’t need to, and you should never count on having enough water to waste on cooking; one of the best things about yucca flowers is the embedded moisture, so take it as a gift and don’t mess with it. Plus, she says it’s good to get used to raw plant fiber, so your body won’t rebel if you have to rely on it.

She tells us the Serrano call yucca “holy weed,” because of its many uses, like fire kindling, rope, sandals, cloth, and soap, almost like a general store.

“Isn’t yerba santa the holy weed?” I ask.

“According to the Spanish, but you know, Indians had their own forms of holy and their own languages of worship. But,” she admonishes us in advance, “you shouldn’t call it ‘holy weed.’ That’s not our language. We call it ‘our Lord’s candle.’ Remember that.”

Before we eat, she wants to show us something. As she peels back the outer layer of the yucca flower, she points to a moth living inside the seed pods.

“There are four kinds of yucca moths, each adapted for one species of yucca,” she explains. “The female moth gathers pollen from a flower, rolls it up and takes it to another flower. She then lays a few eggs inside the flower and inserts the pollen. The pollinated yucca flower becomes a pod filled with seeds, which the moth larvae eat before becoming moths. The larvae eat about half of the eggs a yucca plant produces. Neither the yucca plant nor the yucca moth can exist without the other. No other insect pollinates the yucca plant, nor does the yucca moth pollinate any other plant. They are dependent on each other for their existence, which is called mutualism.”

Mother encourages us to eat. Lizbeth nudges me and whispers, “Are there any larvae in these flowers?”

I shrug. “Why don’t you ask Mother?”

“You ask her.”

Usually, I’ll acquiesce, but this question isn’t worth it. Like many of the questions we ask other people, I already know the answer. In this case, I’m trying to protect Lizbeth from the knowledge of the larvae she will be consuming with the flowers, but I can’t let on. Mother doesn’t believe in protecting children from anything.

___________________________

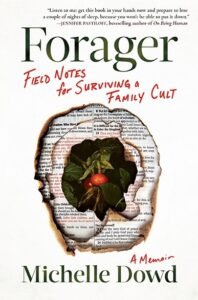

From FORAGER: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult © 2023 by Michelle Dowd. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books.

Michelle Dowd

Michelle Dowd is a journalism professor and contributor to the New York Times, Alpinist, Catapult, and other national publications. She is the 2022 Faculty Lecturer of the Year at Chaffey College, where she founded the award-winning literary journal and creative collective, TheChaffey Review, advises Student Media, and teaches poetry and critical thinking in the California Institutes for Men and Women in Chino. She guides yoga and meditation throughout southern California.