Fabulous Fungi: On the Endless Possibilities of the Mushroom

Meg Madden Explores the Many Ways to Use Mushrooms

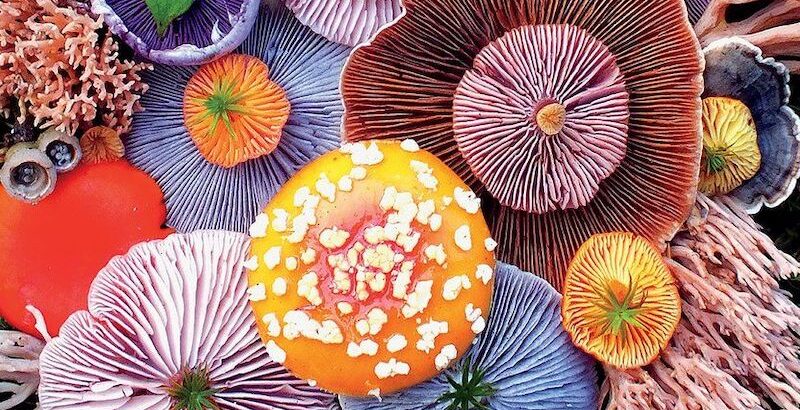

Fungi are everywhere—in our lawns and forests, in and on our bodies, and even lurking in that forgotten Tupperware container in the back of the fridge. While some fungi are harmful, the vast majority are beneficial to their environments and serve important ecological roles.

Some fungi act as parasites, infecting their hosts and sickening or even killing them. Common human ailments such as ringworm and athlete’s foot are caused by fungi. Pathogenic fungi like rusts and mildews regularly cause costly damage to important agricultural crops. Chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, was inadvertently introduced to North America from Southeast Asia at the turn of the twentieth century and in a few short decades wiped out billions of chestnut trees in the United States, nearly causing their extinction. Fungi even attack other fungi. Hypomyces lactifluorum parasitizes species of Lactarius and Russula, transforming them into the choice edible known as the lobster mushroom.

Hands down, though, the fungal parasites that infect insects have to be among the most bizarre. These fungi keep their insect hosts alive but take complete control of their actions, using them as zombie minions to spread their spores for them.

A second group of fungi are the decomposers known as saprobes. Humans have a primal aversion to rotting things, developed to help us avoid eating spoiled food that could cause illness. But decay is an essential part of an ecosystem’s natural cycle and decomposers are nature’s recycling crew. They feed on dead organic matter, breaking it down into nutrients that can then be used by other organisms, and life begins anew. As the only multicellular organisms capable of breaking down lignin, the toughest parts of wood and leaves, fungi act as nature’s cleanup crew. Without them, every tree that has ever died would still be lying about in huge piles like enormous pick-up sticks, and the earth would be buried under an epic leaf pile.

While some fungi are harmful, the vast majority are beneficial to their environments and serve important ecological roles.The third group of fungi enter into mutualistic relationships, called mycorrhiza, with plants, including food crops and the trees in our forests. In fact, about 90 percent of land plants rely on partnerships with mycorrhizal fungi. Underground microscopic fungal filaments, called hyphae, connect with plant rootlets, forming a symbiotic bond. The plant, then tapped into the massive mycelial network of the fungus, has much greater access to nutrients and water.

As part of this ancient bartering system, the fungus receives sugars that the plant produces during photosynthesis, a food the fungus is incapable of making itself. In healthy forests, trees connected via this network, sometimes called the “wood wide web,” can even share water and nutrients with each other. The trees can detect stress in their neighbors and send extra resources their way via the mycelial network to help them through tough times such as periods of drought. The largest and most deeply rooted of these trees are the mother trees. These woodland giants have the capability of linking with hundreds of other trees through their vast, radiating mycelial connections. They share with younger saplings that may otherwise struggle for resources in their highly competitive forest environment. Interestingly, studies have shown that mother trees favor their own seedlings over the seedlings of other trees.

The Fungus Among Us

It is thought that only about 5 percent of the earth’s fungal species are known to humans. Thanks to modern science, intrepid mycologists, and even community scientists, that number is increasing all the time. Compared with what we know about plants and animals, our knowledge of fungi is limited. This may be in part because the bulk of a fungus’s mass is hidden from view—a kind of “out of sight, out of mind” situation. For the most part these organisms tend to live under the radar, making themselves visible primarily when it’s time to make more fungi. Whether we’re conscious of it or not, though, fungi impact our daily lives in both small and profound ways—we are as inextricably intertwined with them as the mycelial web itself.

In their most obvious role, fungi provide us with sustenance in the form of mushrooms. They are more than just delicious; they are high in fiber and a good source of protein, antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals while low in calories, carbs, and fat. Fungi are used extensively in the production of many widely consumed food products—you can thank yeasts and molds, both types of fungi, for wine, beer, coffee, bread, cheese, and even chocolate. Mycoprotein-based meat substitutes are gaining in popularity for ethical and health reasons and because fungiculture has less of an impact on the environment and is less costly than traditional livestock farming. In a less obvious sense, fungi also play an integral role in our food system by building soil health and as mycorrhizal partners for agricultural crop plants.

Just as they can cause illness, fungi are the source for many important pharmaceuticals. Most of the top prescription drugs in the United States are synthesized from plants and fungi. These include drugs used to treat cancer and high cholesterol, as well as antibiotics. The first antibiotic to be isolated from a fungus was penicillin, discovered by Scottish physician Alexander Fleming in 1928. Penicillin, still used today, was incredibly difficult to manufacture at first but was spurred into mass production by the tremendous loss of life due to bacterial infections during World War II. The headline of an ad printed in a 1944 issue of Life magazine declared, “Thanks to PENICILLIN…he will come home!”

In Eastern cultures, mushrooms have been used for centuries to boost the immune and nervous systems, to treat countless ailments such as inflammatory diseases and cancer, and to support mental health and overall vigor and vitality. Traditional medicinal mushrooms such as turkey tail, lion’s mane, reishi, chaga, and Cordyceps are quickly becoming more mainstream in the West, too. These “functional” mushrooms, mushrooms that have health benefits beyond their nutritional value, are now widely available as supplements. And they’re not just embraced by the alternative health crowd—universities and big pharmaceutical companies are spearheading cutting-edge clinical trials to test and hone their efficacy as treatment for many of modern society’s toughest health issues.

Entheogens, naturally occurring psychoactive substances, have been used in the spiritual ceremonies of Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. In the United States in the mid-1950s, psilocybin—a psychoactive substance found in most species of the genus Psilocybe— was being studied for its therapeutic benefits as an aid to psychotherapy treatment for certain mental health disorders.

This early research, spearheaded by a group of psychology professors, even had the backing of one of America’s most prestigious universities. These psychoactive mushrooms, dubbed “magic mushrooms” or “’shrooms,” went on to gain public notoriety as a recreational drug during the 1960s when their mind-expanding properties became an integral part of the free-thinking hippie movement. In the early 1970s, the US government launched the war on drugs as backlash against America’s youth counterculture, who had been rocking the boat with their political views, protests against the Vietnam War, unconventional alternative lifestyle, and use of psychedelic drugs to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

The unfortunate result was that in 1970 psilocybin was listed as Schedule I under the Controlled Substances Act, lumped in with heroin and other highly addictive drugs deemed to have no currently accepted medical use. Consequently, research into the clinical benefits of psychedelics came to a screeching halt, but attitudes about the substance have evolved with time. Fast-forward several decades and psilocybin is now once again the subject of cutting-edge medical research, showing great promise for a multitude of applications such as treating individuals with PTSD, severe depression, and substance use disorder, and alleviation of end-of-life distress for the terminally ill.

The Future Is Fungi

In response to the climate crisis, scientists are increasingly interested in the roles that fungi can play to help meet climate change goals now and far into the future. Humans are consuming more resources than the planet can sustainably produce and creating more waste than we can process in an environmentally responsible manner, which is taking a toll on the world. Industries that contribute significantly to consumption, the waste stream, and pollution are turning to applied mycology—ways that fungi can be used as affordable, sustainable, eco-friendly, low-environmental-impact solutions to some of these challenges.

There is great potential for fungi to play a critical role in cleaning up waste, pollutants, and environmental disasters.For example, the construction industry is looking into the viability of mycelium-based green building materials. Fungal mycelium grows quickly and can be easily formed into bricks, insulation, and other components, using minimal resources and therefore having a greatly reduced environmental footprint. Once cured, mycelium-based materials are incredibly strong and durable, and are highly resistant to moisture, mold, and fire. Nontoxic and completely biodegradable, instead of becoming landfill at the end of their use, they can be composted or even used as a substrate for growing food.

Visionaries in the world of clothing and textiles, an industry with one of the biggest negative environmental impacts, are turning to mushroom pigments for eco-friendly dyes to replace highly toxic chemicals, and mycelium-based bio-fabrics as an alternative to traditional cloth such as cotton, which uses a tremendous amount of water, herbicides, and pesticides to produce. Fungi-based textiles are soft, durable, breathable, and naturally antimicrobial. This may seem like futuristic science fiction, but fungi fashion is already hitting the runways—and becoming more widely available to the general public—in the form of clothing made from mycelium, and shoes, jackets, and purses made from vegan mushroom leather.

There is great potential for fungi to play a critical role in cleaning up waste, pollutants, and environmental disasters. Mycoremediation—which literally means “fungus restoring balance”—is a form of biological remediation that uses living organisms to remove contaminants from soil and freshwater and marine environments. Certain fungi can survive in extreme conditions where most organisms cannot, making them ideal for use in isolating and breaking down agricultural and industrial pollutants, oil spills, and even radiation.

Some fungi are able to remove heavy metals from the environment by bioaccumulating them in their tissues. There are even mushrooms that can digest plastic. For example, Pestalotiopsis microspora can survive solely on polystyrene as its food source. Plastic can take hundreds of years to decompose on its own, but the mycelium of P. microspora begins to break it down into organic matter in a few short weeks and can digest it completely within a few months’ time. Ideally, this biotechnology could be utilized in both small-scale applications such as home recycling kits, which would put plastic reduction into the hands of individuals; and because it can thrive in conditions where there is no light or air, it is a perfect candidate for large-scale municipal projects such as cleaning up landfills.

Even the common edible oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) can consume plastic. If ongoing research proves that they are safe to eat once they have done their job, these humble mushrooms could potentially perform the dual duty of reducing plastic waste while helping to alleviate famine and food insecurity.

__________________________________

Excerpted from This Is a Book for People Who Love Mushrooms by Meg Madden. Copyright © 2023. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group.