Larissa Pham on Parasocial Relationships and Trying to Tell an Emotional Truth

The Author of Pop Song in Conversation with Zack Graham

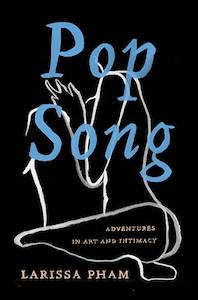

Larissa Pham’s new book, Pop Song, is out now from Catapult. She recently spoke to Zack Graham about internet celebrity, the vagaries of genre, and what it means to tell the emotional truth.

*

Zack Graham: I want to start by asking a question invoked by the subtitle of your book (“Adventures in Art and Intimacy”). What, in your view, is the relationship between art and intimacy?

Larissa Pham: I like this question a lot! I think that our experience of art can be, and often is, a deeply intimate thing. It is felt. Even when we’re experiencing art in a communal context (like at a show or at a concert, for example), our experience of it is so private and internal. We’re never going to feel exactly what someone else feels and that’s special. Art moves us; it can shift things in us. And art (and literature, and culture) is uniquely powerful in how it can reach across time and space to shift us in precisely those ways.

ZG: In the chapter “Body of Work” you talk about how you got your start publishing on Tumblr when you were in high school. Can you talk a little bit about the experience of getting famous online as a young “poet” (your words) back then? How does your social media “fame” now differ from internet “fame” back then?

LP: It’s interesting to reflect on that because “fame” then really meant something different. For one, the scope was much smaller. You could be well known in a community and have a readership, or at least, a follower count, and never have to worry about going viral—I mean, what even was going viral back then? Getting a bunch of notes and reblogs all contained in the Tumblr dashboard? Now it’s so easy to go viral, almost like a fluke, and the reach is much wider, and the benefits of it, if there even are any, are so low. (Earlier this year I went viral for a tweet about writing fiction and I don’t think it got me any pre-orders, though I did drop a link. But I also worried that then people would think Pop Song is a novel or something.)

What I did have back in the Tumblr days was a readership and a community that I felt very close to, very in conversation with in some ways, and it’s many of those readers who still read and support my work now. That felt, and feels, really special! I wouldn’t say I’m social media famous in any way now. Somehow I have 10,000 followers on Twitter but I hate it (Twitter, I mean). It’s not a place for dialogue or exchange or good-faith interpretation. It’s absolutely a site where people form parasocial relationships with people they don’t know. (And I do suppose I know a little about that from having similar things happen to me when I was younger.) Whatever following I have on social media now, it doesn’t really feel tangible… I suppose I’m happy if people are interested in what I have to say, but I’ve learned that it’s not really helpful to have thoughts on that platform.

ZG: I’d like to ask a question about sexual objectification. Your first book was an erotic novella called Fantasian which addresses some of the anxiety you felt being sexually objectified as an Asian woman throughout your life, and specifically during college.

Your essay “Body of Work” in Pop Song talks a little bit about that but has more to do with your relationship to BDSM. You write so well about sex and your sexuality, and yet clearly there exists within you a conflict, as you are an artist of color who makes art about sex, and yet you struggle against the inherent fetishization of your persona as sexual. Can you talk a little bit about how you approach that balance?

LP: It’s definitely complicated… I feel like in the past, a lot of my efforts in this arena were about trying to stay in control. To have agency over my own image… I wrote a sex column for Nerve for about a year, from 2015-2016, then I wrote Fantasian, and I’ve chosen to write about these topics in this book as well, including experiences of trauma. For a while in my mid-twenties I thought, if I really wanted to be seen in a different light, I needed to write about different subjects, right? I started writing book reviews, I started writing criticism more seriously. And yet I have returned here. I’m always wary of how I (and my work) can be perceived, especially in light of recent racialized, gendered violence against Asian American women. But I would say that I am a little less acutely conscious of how I am perceived than I was when I wrote Fantasian. I’m more concerned now with trying to get things right, trying to tell an emotional truth. That sex is in it is part of it, is because it’s part of life. So I will write about it, and continue writing about it. I’m less worried about trying to balance it in a political or defensive sense.

It’s so easy to go viral, almost like a fluke, and the reach is much wider, and the benefits of it, if there even are any, are so low.

ZG: Now I want to ask a question about your use of direct address throughout the book. It’s clear you’re not addressing the reader when you employ direct address—you’re addressing a friend, or a lover, or both. Were all of these people different people? Or would you say you are speaking to one unified lover-friend throughout Pop Song, a foil for the things you’ve seen, experienced, or felt?

LP: It’s interesting, I’ve been asked this question a few times and you’re the first person to have suggested that the lover addressed might be a sort of foil—both the person who inspired the address and also a figurative you that becomes a foil for my character. So, yes, absolutely the latter. I think this always happens when writers write to a specific you—it’s the person, but it’s also not the person at all, don’t you think? It’s the space they occupy in our thoughts, the person they become to us.

ZG: In your essay “Dark Vessel,” you criticize yourself for relying “on the language of the body too often… ” What do you think is the “language of the body?” Do you think bodies speak one language? Multiple languages? How do bodies speak?

LP: I get really tangled up when I think about language. It’s so hard to only rely on words. When I think about things that moved me, I don’t always have words for it, and sometimes, that feels like I don’t have language. But those things that moved me, they weren’t always speaking to me in words—in fact, they usually weren’t. When I think about the language of the body, I think about how sometimes, when I’m in a fight with someone I love, I can’t use words to communicate anymore. Instead, I want to hold them—I have to, I want to. And in that touch, I’m expressing something I can’t with speech. I think that we communicate a lot in touch, in glances, in gestures. Not even just between intimate partners, but with strangers. It’s a huge part of what we’ve lost this past year, being able to communicate in that way with each other. We speak to each other in so many ways—through dance, through communion. It’s something I’ve missed a lot this last year.

ZG: Late on Pop Song takes a compelling turn toward poetry, prose poetry, and micro-essays centered around the emotional devastation of a breakup. I found this to be such a refreshing and compelling section of the book. Why do you think you wrote this piece of the book in such a bold and unconventional way, where the rest of the book’s chapters are fairly straightforward?

LP: I’m happy you found something to appreciate in that section, as I think it’s the one critics have the most trouble with! When I was writing the Break-up Interludes (which I’m still very pleased to have titled them) I was thinking about the book as an album. I’ve always enjoyed moments in an album where the music breaks away from an expected form—like in “Good Guy,” which I write about, where the audio dissolves into conversation in the last few seconds. Or that voicemail from Frank Ocean’s mom! I also couldn’t figure out a way to write that breakup in a linear, narrative sense—it felt like something I had to get at from different angles, these moments where I felt slippages or conflict. There was no narrative of that moment of dissolution—not one that I could render or was interested in rendering. So I thought if I could write those minute moments, with attention, and sketch a path to the eventual coming-apart, then it would feel most accurate to how it felt at the time. If the whole book had been written that way, I’m sure it would have been overwhelming. But I think it was the right move for that section.

ZG: I’m going to write in full my favorite sentence in your book because paraphrasing it simply wouldn’t do it justice. This sentence appears during the book’s final chapter “On Being Alone,” which is an account of your experience traveling to China on a luxury fashion company’s dime. (For context, this sentence appears after you have dinner with a good friend.)

It seemed incredible to me that I could have come so far—from Portland to New Haven, from Provincetown and to New York, to Taos, to Condesa and Crown Heights and my painting studio in Sunset Park—and yet, at the end of all this, remained doing all the same ordinary things.

The irony embedded in this sentence, of course, is that you’re not doing the same ordinary things at all. You’re publishing your second book before your 30th birthday. You’re writing a new historical novel involving your Vietnamese family. You’re painting and you’re living and you’re loving in a world that’s just coming out of the frost of Donald Trump and the coronavirus pandemic. How do you feel about everything you’ve accomplished? You most certainly should not feel ordinary…

LP: You’re too kind! I do still feel very ordinary… but I think that there’s much to be learned from observing ordinary life. I’m very grateful to have had the opportunities to work on these big, long projects that have been formative and important for me. But I will try to stay in my cave, where work and gratitude live. If I get a big head from thinking I’m extraordinary, then I’ll lose touch with my favorite things, the small things.

__________________________________

Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy is available from Catapult. Copyright © 2021 by Larissa Pham.

Zack Graham

Zack Graham’s writing has appeared in The Nation, Rolling Stone, GQ, The Believer, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. He has completed a collection of short stories and a novel.