The shades are drawn, the apartment dark except for the lunar glow from the kitchen and, in the living room, the flicker of the twelve-inch black-and-white screen. My parents and I are silent. The only signs of life squawk and jitter inside the massive console TV. My mother and I have been watching all day, and now my father has come home to join us.

Dad and I share the love seat. It’s comfortable, sitting close. Mom lies on the couch under a brown-and-orange crocheted blanket that she found in a secondhand shop. Sewn onto the blanket is a hand-embroidered silk label that says: Made especially for you by Patricia.

“Look, Mom,” I say. “Your blanket’s lying.” “Who isn’t?” my mother says.

Though it’s not especially hot outside, our air conditioner is blasting. We’re chilly, but we can’t leave the room or adjust the thermostat. Changing channels is beyond us. We’d have to get up and fiddle with the antenna. My father is exhausted from work and the long subway ride home. My mother’s migraines have grown so unpredictable, her spells of vertigo so severe, that she’d have to cross the carpet on her knees like a penitente. I can’t even speak for fear of hearing the reedy, imploring voice of my boyhood: Hey, Mom, hey, Dad, what do you think? Would another channel be better?

Another channel would not be better. The Rosenbergs would still be dying.

*

All day, the networks have been interrupting the regular programming with news of the execution, which, without a miracle, will happen tonight at Sing Sing. It’s like New Year’s Eve in Times Square: the countdown to the ball drop.

In between updates, we’re watching The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Ozzie and Harriet Nelson are comforting their son Ricky, who hasn’t been invited to the cool kids’ party.

A reporter interrupts Ozzie and Harriet to read a letter from President Eisenhower. He’s stumbling over the hard words. The abominable act of treason committed by these Communist traitors has immeasurably increased the chances of nuclear annihilation. Millions of deaths would be directly attributable to the Rosenbergs’ having stolen the secret of the A-bomb detonator for the Russians. An unpardonable crime for which clemency would be a grave miscarriage of justice.

Miscarriage isn’t a hard word. The reporter must be rattled.

It’s the third time today that Mom and I have heard the president’s letter. Earlier, the reporters got the words right. Maybe it’s harder for them too, as zero hour approaches.

There’s an interview—also replayed—with the doughy-faced Death House matron, who wants the TV audience not to judge her because of her job. This is her chance to tell us that she is doing God’s work. “Ethel was an angel. One of the kindest, sweetest, gentlest human beings I ever met in my life. You don’t see many like that. Always talking about how much she loved her children. Always showing photos of those two little boys. She was very sad.”

“Damn right she’s sad,” says my father.

Back to Ricky Nelson sneaking into the party and being tossed out by the cool kids.

Cut to an older reporter explaining that the attorney general visited the Rosenbergs in prison. Their death sentences could have been commuted if they’d consented to plead guilty and name their accomplices. But the fanatical Soviet agents refused this generous offer.

“They were stupid,” Dad says. “They should have said whatever the government wanted. They should have blown smoke directly up Dwight D. Eisenhower’s ass.”

“Ethel was always stupid,” Mom says. “Stupid and proud and full of herself and too good for this world. She wanted to be an actress. She studied opera. She sang for the labor strikers, those poor bastards freezing their behinds off, picketing in the dead of winter. So what if they didn’t want to hear her? She had a beautiful voice. She was kind. Brave! They shouldn’t have killed her.”

I say, “They haven’t killed her yet.”

My parents turn, surprised. Who am I, and what am I doing in this place where they have learned to live without me? We hardly recognize one another: the boy who left for college, the son who returned, the mother and father still here.

*

Two weeks before, I’d graduated from Harvard, where I’d majored in Folklore and Mythology. I’d written my senior thesis on a medieval Icelandic saga. I’d planned to go to graduate school in Old Norse literature at the University of Chicago, but I was rejected. I’d had no fallback plan. The letter from Chicago had papered a wall between the present and a future that looked alarmingly like the past.

In a way it was a surprise, and in another way it wasn’t. College was always a dream life. My parents’ apartment was always the real one. The new TV and the air conditioner were bought to keep my mother entertained, to stave off the heat that intensifies her headaches, and to console me for having wound up where I started.

My parents had so wanted me to live their parents’ immigrant dream. If I’d had a dollar for every stranger they told I was going to Harvard, I wouldn’t have needed the scholarship they never failed to add that I’d gotten. They’d assumed I’d become a Supreme Court justice or at least a Nobel Prize laureate.

Somehow I’d failed to mention that I was learning Old Norse to puzzle out the words for decapitation, amputation, corpses bristling with spears. I told them about my required courses, in history and science. With every semester that passed, my parents felt less entitled, less qualified to ask what I was studying. What, they wondered, would they—a high school teacher, a vendor of golf clubs—know about what I was doing at Harvard? During the summers, I’d stayed in Cambridge, mowing lawns, washing cars, working in a second-hand bookstore to pay for what my scholarship didn’t cover.

*

We’re back to Ozzie and Harriet telling Ricky he should throw his own cool party. But none of the cool kids will come.

“Ridiculous,” says Dad. “The kid’s a celebrity teen heartthrob. Everyone goes to his parties.”

Outside the White House, protestors wave signs: The Electric Chair Can’t Kill the Truth. Or Rosenbergs! Go Back to Russia! God Bless America. A reporter intones, “The Rosenberg case has excited strong passions. It’s incited an almost . . . political crisis at home and around the world. Demonstrators were killed in Paris while attempting to storm the US embassy.”

Then it’s back to Ricky moping on his bed until Harriet assures him that one day he’ll be a cool kid and give the coolest parties.

Someone in the control room must have gotten something wrong. Or right. The Nelsons vanish. Blip. Blip. Fade to black. Filling the screen is a photo of an electric chair, so menacing and raw, so honest about its purpose—

“God help her,” my mother says.

“We’re not supposed to be seeing that. Someone just got fired,” I say.

“Holy smokes,” says my father. “Hilarious,” says Mom. “Funny guys.” “I wasn’t joking,” I say.

“Sorry,” my father says. “Two boys,” Mom says.

Dad says, “I apologized, damn it.”

“Not you two. Not Ricky and David. Michael and Robbie Rosenberg. Those poor boys! Not Ozzie and Harriet. Ethel and Julius. Look how people live on TV. Teenage-party problems.”

“It’s not real,” says my father. “The Nelsons live in a mansion with servants.”

And now a commercial: A husband growls at his wife until she hands him a glass of fizzy antacid. There’s a jingle about sizzling bubbles. Sizzle sizzle. The husband drinks, it’s all kisses and smiles. It was just indigestion!

Here’s John Cameron Swayze reminding us that, without a last-minute commutation, the Rosenbergs are scheduled to—

“Sizzle,” says my father.

“Stop it,” says my mother. “Simon, make him stop it.”

“Dad’s nervous,” I say. “That’s what he does when he’s nervous.

It’s not as if you just met him.”

“Two hours and fifty-four minutes,” chants John Cameron Swayze. My mother says, “Where are they getting fifty-four?”

“They know something,” says Dad. “Gloomy Gus,” says my mother. “Look who’s talking,” says Dad.

“Are you okay, Simon darling?” my mother asks me. “Are you feeling all right? You don’t have to watch this, you know.”

But I do. I have to watch it. I have left the glittering world of ambitious young people bred for parties and success, students who had already succeeded by getting into Harvard. I’ve lost my chance to become one of them. They have all gone ahead without me. I’ve said farewell to the chosen ones with their luminous skin and perfect teeth. I have returned for this summer or forever because—I tell myself now—this is where I am needed. Watching TV tonight with my parents is my vocation, the job I was born to do.

“Anyone hungry?” my mother asks. “I can’t eat.” “You’ll eat later,” says Dad.

“Later, after Ethel is dead, we’ll grill steaks on the fire escape.” “That’s not what I meant,” says my father.

*

We’ve missed the opening of I Love Lucy. Lucille Ball is telling her friend Ethel about a mystery novel she’s just read.

“Ethel,” murmurs my father. “Not Lucy’s Ethel. Our Ethel . . . ” “No one will ever have that name,” says Mom. “All the Ethels will

change their names. Already there are no Rosenbergs. Ten years from now you won’t meet one Ethel. You won’t find a Rosenberg in the phone book.”

“Don’t tell me the end of the mystery,” Lucy’s Ethel is saying. Lucy says, “Okay. I promise. The husband did it.”

“That’s the end!” says Ethel.

“No,” says Lucy. “They arrest the husband. That’s the end.” “You can say that again,” says Dad. “The husband did it.”

“We don’t know,” says my mother. “Nobody knows what Julius did.”

“Julius did it. He and the brother-in-law were in bed with the Russians. She typed some papers because the baby brother asked. Those guys wouldn’t trust a woman with sensitive information. The brother sold them for a plea deal. And the Feds threw Ethel into the stewpot for extra flavor. It’s spicier with the housewife dying. The mother of two with the sweet little mouth.”

“Not everyone thinks that mouth is sweet.” Is Mom jealous of a woman about to be executed? Ethel had a beautiful voice. Ethel sang for the strikers. Maybe my mother envied Ethel, but she doesn’t want her to die.

“Look, Simon. It’s Jean-Paul Sartre. Hush now. Quiet. Listen.” Why is Sartre at Lucy and Ricky Ricardo’s? But wait, no, he’s in

Paris, in a book-lined study. And how does Mom recognize Sartre?

I can never let my parents suspect what a snob I’ve become. My mother is a teacher. She knows who Sartre is.

What did I do at college that raised me so far above them? I’d studied the university’s most arcane and impractical subjects. Each semester I’d taken classes with a legendary professor, Robertson Crowley, an old-school gentleman adventurer–anthropologist–literary theorist who had lived with Amazonian healers, reindeer herders in Lapland, Macedonian bards, Sicilian witches, and Albanian sworn virgins who dressed and fought like men. I’d studied literature: English, American, the Classics, the Russians and the French, with some art history thrown in and the minimum of general education.

While I memorized fairy tales and read Jacobean drama, my father was selling Ping-Pong paddles at a sporting goods store near City Hall. And like the angel guarding Eden, my mother’s migraines drove her from her beloved high school American history classroom and onto our candy-striped, fraying Louis-the-Something couch.

The interpreter chatters over Sartre’s Gallic rumble. “United States . . . legal lynching . . . blood sacrifice . . . witch hunts . . . ” “Blowhard,” Dad says.

“Sartre says our country is sick with fear,” says my mother. “Everyone’s sick with fear. That’s why he’s a famous philosopher?”

Mom says, “To be honest, I haven’t read him. Simon has. Have you read Sartre, darling?”

“Yes,” I say. “No. I don’t know. I don’t remember. In high school.

Yes. Probably. Maybe.”

“I know you read the Puritans. I gave them to you, right? I remember your reading Jonathan Edwards, Cotton Mather. And look, the Puritans have come back. Like zombies from the dead.”

“They never died,” says Dad.

I say, “I wrote my college essay on Jonathan Edwards. Remember?” “That’s right,” my mother says. “Of course. Didn’t I type it for you?”

No, she didn’t. But I don’t say that. I’m ashamed of myself for expecting my mother to remember the tiny triumphs that once seemed so important and were always nothing.

*

Ricky Ricardo is keeping secrets. Someone delivers curtains that Lucy didn’t order. The husband in the mystery novel wrapped his wife’s corpse in a curtain. Is Ricky plotting a murder? Close-up on Lucy’s fake-terrified eyes jiggling in their sockets.

Cut to a commercial for Lucky Strike, long-legged humanoid cigarettes square-dancing. “Find your honey and give her a whirl, swing around the little girl, smoke ’em, smoke ’em—”

“Smoke ’em,” says my father.

“Please don’t,” says Mom. “I’m begging you.”

Did Ricky kill Lucy? We may never know because the Rosenbergs’ lawyer, Emanuel Bloch, is reading a letter from Ethel. He’s read it aloud before, but it hasn’t gotten easier.

“You will see to it that our names are kept bright and unsullied by lies.”

You will see to it that our names are kept bright and unsullied by lies.

The attorney’s voice is professional, steady, male, until it breaks on the word lies.

“Ethel’s dying wish,” says my mother.

Dying wish. So much power and urgency packed into two little words: superstitious, coercive, freighted with loyalty, duty, and love. A final favor that can’t be denied, a test the survivors can’t fail.

My father says, “How come her dying wish wasn’t, Take care of the boys?”

“We don’t know what she told her lawyer,” says Mom.

*

The newscaster tells us yet again how the state’s case hinged on a torn box of Jell-O that served as a signal between the spies. The Communist agent Harry Gold had half the box, Ethel’s brother the other half. Gold’s handlers instructed him to say, This comes from Julius. The jagged fragments of the Jell-O box fit, like jigsaw puzzle pieces.

“She should have stayed kosher,” Mom says. “Observant Jews don’t eat Jell-O. Cloven hoof, smooth hoof, the wrong hoof, I forget what.”

“Some rabbi ruled that Jell-O is kosher,” says Dad. “Probably the Jell-O people found a rabbi they could pay off.”

“Was Ethel kosher?” I ask.

“Who cares? There was no torn Jell-O box,” my father says. “Except in someone’s head.”

*

Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s right-hand man, appears on screen, grinning like the mechanical monsters outside the dark rides on Neptune Avenue.

“In his head,” says Dad. “The strawberry Jell-O is in Roy Cohn’s head.”

My mother curses in Yiddish.

I say, “Did they specify strawberry?” “Is this a joke to you, Simon?”

Flash on the famous photo of Ethel and Julius in the police van. How sad they look, how childlike. Two crazy mixed-up kids in love, separated by their parents.

Then back to Lucy. Ricky isn’t plotting to kill her. He’s throwing her a surprise birthday party!

“Birthday secrets, atomic secrets. Everyone’s paranoid,” says Mom. “Rightly so,” says Dad.

“Two hours to go,” says my mother. “There’s still hope,” says Dad. “There’s no hope,” says my mother.

The air conditioner is pumping all the oxygen out of the room. I want the Rosenbergs to live, but meanwhile I can’t breathe. I want them to be saved. I want the messenger to hurtle down Death Row, shouting, Stop! Don’t throw that switch! Meanwhile some secret shameful part of me wants them dead. I want this to be over.

Lucy and Ricky wear party hats. Lucy blows out the candles, and the camera swoops in for the big smoochy kiss. How can anyone not think of Ethel and Julius?

*

The networks stop the sitcoms. The action is at the jail. The two Rosenberg boys get out of the car, holding the lawyer’s hands, tugging him forward, the younger boy more than the older, trying not to run from the shouting reporters, the popping flashbulbs, the rat-tat-tat of the cameras.

“The Rosenberg sons,” says the newscaster. “Going to see their parents for the final time.”

“The older boy understands, not the little one,” says Dad.

“They both do,” says my mother. “We’re watching two kids whose parents are about to be murdered. Real children. Not child actors. Murdered on TV.”

The camera finds some carpenters checking the new fences around the prison. Protests are expected, and the workers keep looking over their shoulders to see if the angry mob has arrived.

Where is the angry mob?

Union Square. The silent protestors hold signs: Demand Justice for the Rosenbergs, Stop This Legal Murder. Close-up on a pretty girl in tears, then a sour old hatchet-faced commie with a sign that says, If They Die, The Innocent Will Be Murdered. Then back to the barricade builders, who have finished, though no one has come to test their work.

*

A flash, and two newscasters appear like genies from a bottle. “For those who have just joined us . . . This afternoon our attorney general informed the president that the FBI has in its possession evidence so damning, conclusive, and highly sensitive that, for reasons of national security, it could not be introduced at the trial.”

The dark walls of Sing Sing bisect the screen. Another man gets out of a car.

“Our sources have identified the man as the Rosenbergs’ rabbi—” My mother says, “The rabbi. That’s the case against them there.

The Dreyfus Affair, Part Two.”

“Ethel and Julius were hardly Jewish,” my father says. “Their god was Karl Marx. Remember him? Opiate of the people. Jewish Communists don’t think they’re Jews until Stalin kills them.”

“Killed them,” I say. “Stalin’s dead.” Why am I correcting my father? Who do I think I am?

“Blood is blood,” says my mother. “Ethel and Julius were Jewish.” “Are,” I say. “Are Jewish.”

“Optimist,” says Mom. “And you? Still Jewish? After four years among the Puritans?”

“Of course,” I say. But what does that mean? I’d wanted Harvard to wash away the salt and grime of Coney Island. Now I feel as if a layer of skin has been rubbed off along with it. At school I’d copied out a quote from Kafka: “What do I have in common with Jews? I hardly have anything in common with myself and should quietly stand in the corner, content that I can breathe.” Only now do I realize how far that corner is from my parents.

What kind of Jews are my mother and father? We don’t keep kosher or go to temple or celebrate the holidays. Do they believe in God? We don’t discuss it. It’s private.

On Brighton Beach, on the boardwalk, you see numbers tattooed on sunbathers’ arms. Whatever we believe or don’t, Hitler would have killed us. Had Kafka lived, he might have discovered how unfair it is, that the murderers who hate us are what we have in common. My parents are Roosevelt Democrats. They believe in America, in democracy. They believe that Communists were willfully blind to the crimes of Stalin. But America is a free country. Go be a Communist if you want, just don’t try to bring down our republic. My parents believe that McCarthy is the devil. He is the threat to democracy. His investigations are the Salem witch trials all over again, this time run by a fat old drunk instead of crazy girls.

My parents long for Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt’s sweet voices of reassurance and comfort. They never miss Eleanor’s syndicated column, “My Day.” Lately she’s been reporting from Asia, visiting orphanages, lecturing on human rights, meeting refugees from Communist China.

“Come to administer last rites—” the newscaster says. “Jews don’t have last rites,” Dad says. “Moron.” “Maybe the rabbi can give her some peace,” says Mom.

“Forty-five minutes,” says Dad. “The rabbi better talk fast.”

A man in coveralls enters the prison. It’s the electrician who will see that “things” run smoothly. Shouldn’t he have come earlier? Maybe he’d rather not hang around, contemplating his crappy job. A few beers in a commuters’ bar in Ossining sounded a lot better. Several reporters have noted that, due to the expected influx of protestors and the press, local businesses will stay open late.

Another reporter says we’re seeing the two doctors who will pronounce the Rosenbergs dead.

“Nazi doctors,” says my mother. “How is this different from Dr. Mengele?”

I remember Mom covering my eyes with her hand at the movies during a newsreel about the death camps. I peeked between her fingers at the living skeletons pressed against a fence, staring into the camera. My mother’s ring left a sore spot on the bridge of my nose.

“Not every doctor is Mengele,” says my father. “The prison docs aren’t experimenting on twins.”

Mom says, “Franklin and Eleanor would never let this happen.” Twenty minutes. Fifteen.

Ethel Rosenberg is reported to have kissed the prison matron goodbye, a sweet little peck on the cheek. A photo of Ethel and Julius kissing flashes onto the screen. If we can’t see them strapped in the chair, at least we can see their last embrace.

*

In the kitchen, the light above the table blinks. “That’s that,” Mom says. “Adios, amigos.”

“That’s not possible,” my father says. “Scientifically speaking.” Blink blink blink. What was that?

*

We stare at the walls of Sing Sing. A helicopter drones overhead. Up in the tower, a prison guard waves both arms like an umpire ruling on a play. Safe!

The reporters have revived. “A guard appears to be signaling that the execution is over. Ladies and gentlemen, I think everyone would agree that it’s been an extraordinary day for Americans everywhere and for those following this dramatic story from all over the world.”

My mother is weeping quietly. My father perches on the edge of the couch and tries to put his arms around her. He hugs her, then hoists himself up and, groaning, sits beside me.

A man appears in the prison doorway. “Reporter-columnist Bob Considine witnessed—”

Reporter-columnist Bob Considine looks shaken. His clipped robotic delivery makes him sound like a Martian emerging from a flying saucer. We come in peace, the Martians would say, but that’s not what Bob Considine is saying:

“They died differently, gave off different sounds, different grotesque manners. He died quickly, there didn’t seem to be too much life left in him when he entered behind the rabbi. He seemed to be walking in time with the muttering of the twenty-third Psalm, never said a word, never looked like he wanted to say a word. She died a lot harder. When it appeared that she had received enough electricity to kill an ordinary person, the exact amount that killed her husband, the doctors went over and pulled down the cheap prison dress, a little dark green printed job—”

“A cheap prison dress! Ethel was such a clotheshorse!” my mother says, through tears.

“—and placed the stescope . . . steterscope . . . I can’t say it . . . stethoscope to her and looked around and looked at each other—”

“All those doctors and electricians,” Dad says, “they can’t even get that right.”

“—looked at each other rather dumbfounded and seemed surprised that she was not dead.”

“Her heart kept beating for her boys,” says Mom.

“Believing she was dead, the attendants had taken off the ghastly snappings and electrodes and black belts, and these had to be readjusted. She was given more electricity, which started the game . . . that . . . kind . . . of ghastly plume of smoke that rose from her head and went up against the skylight overhead. After two more jolts, Ethel Rosenberg had met her maker, and she’ll have a lot of explaining to do.”

“He’ ll have a lot of explaining to do,” says my mother. “In hell.” “He’s doing his job,” Dad says. “Explaining why two murders should make us feel safer.”

*

I can’t get past that one word: game. Started the game of the ghastly plume of smoke coming from Ethel’s head. The game. Did Bob Considine really say that? Did I hear him wrong? I can’t ask my parents. Game is what I heard.

“Please don’t cry,” I beg my mother. “It’s bad for you.” “It’s good for me,” she says.

“Go out,” Dad tells me. “You’re young. It’s early.”

I go over to the couch, lean down, and kiss my mother goodbye. She reaches up to cradle my face. Her hands are soft, unroughened by years of dishes and laundry, and, as always, cool. Cooler than fever, cooler than summer, cooler than this cold room. Once her hands smelled of chalk dust, of the dates she wrote on the blackboard: 1620, 1776, 1865. Now they smell of lavender oil. Soothing, my mother says. I put my hands over hers. Her graduation ring, which I’ve always loved, presses into my palm. In the center is an onyx square, studded with diamond specks spelling out 1931: the year she graduated from high school. Microhinges flip the onyx around, revealing its opposite face, a tiny silver frame around a tinier graduation photo of Mom: smiling, hopeful, prettier than she would ever be again. “Poor Ethel,” says my mother.

“Poor Ethel.” I’m still thinking of her in the present tense. “Be safe, sweetheart,” my mother says.

“I love you,” I tell my mother, my father, the room.

“Have fun,” my father calls after me. “Just stay off the Parachute Jump.”

*

Depending on the stoplights, the traffic on the corners, and whether I take the streets or the boardwalk, it’s between a twelve to fourteen minute walk to the amusement park. I can do it with my eyes closed, like a dog, by smell, into the cloud of hot dog grease, spun sugar, sun lotion, salt water. I can follow the rumble of laughter, the demented carousel tunes, the screams carried on the wind from the Cyclone. I could find my way by the soles of my shoes sticking to the chewing gum on the sidewalk, rasping against the sand tracked in from the beach.

Thousands are weeping in Union Square, in San Francisco, London, and Paris. But in Coney Island, it’s a regular fun Friday night. Guys plug away at shooting galleries, massacring yellow ducks while their girlfriends squeal because they are about to win the stuffed animals they’ll have to lug around all night like giant plush albatrosses. Their kid brothers slam their skinny hips into the pinball machines, while the children stuffing themselves with cotton candy look first happy, then glum because the melting candy is tasteless and sticky and getting all over their faces.

I buy three hot dogs, double fries, a lemonade. Clutching the bag to my chest, I take the food up to an empty bench on the boardwalk. I gulp down my dinner, gaze at the sky, and try to recall where I’d read a passage about the sky turning a glorious color for which there is no name. In the story the sunset reminds the hero that everything in the world is beautiful except what we do when we forget our humanity, our human dignity, our higher purpose.

The only thing the sky says to me is that the third hot dog was a mistake. I feel anxious and queasy. The spectacular pink and cerulean blue purple into the color of a bruise, and the wispy charcoal cloud is the plume of smoke rising from Ethel’s head.

To my right the Parachute Jump flowers and blossoms and drops, flowers and blossoms and drops, like a poisonous jellyfish, a carnivorous undersea creature.

Just after the Second World War, for reasons never made clear, my father’s little brother, Mort, was parachuted into Rumania, where he disappeared forever. His body was never found. I can’t leave the house without my father warning me to stay off the Parachute Jump.

It’s a tic. He can’t help it.

I’d avoid it without his advice. The height has always scared me.

The fragile canopies, the probable age of the suspension lines.

I head along Neptune Avenue, past the dark rides. The Spook-A-Rama, the Thrill-O-Matic, the House of Horrors, the Devil’s Playground, the Den of Lost Souls, the Nightmare Castle, the Terror Tomb. Then along the Midway, past the crowds waiting to see the Chicken Boy, the Three-Legged Girl, the Lobster Baby, the Human Unicorn. Then on to the thrill rides, the Wild Mouse, the Thunder Train, the Rocket Launch, the Twister, the Widowmaker, the Spine Cracker.

How could any of it be scarier than Ethel’s death? Not the goblins, the pirates, the skeletons and laughing devils, not the shaming of the freaks, the plunging freefall, the vertigo, the fear of flying off the track, of being launched into space, the fear of the parachute failing to open and of the eternity before you hit the ground.

As always, I wind up at the Cyclone. The line isn’t long. The ticket taker knows me. Hey, Simon. Hey, Angus. How’s it going. Fine, thanks, and you? Same old, same old.

I give Angus two dimes. He hands me a ticket. I walk through the gate in the fence surrounding the wooden roller coaster. I fold my long legs into the compartment in the middle of the little train. I lower the safety bar over my lap.

I wait for the ride to begin.

*

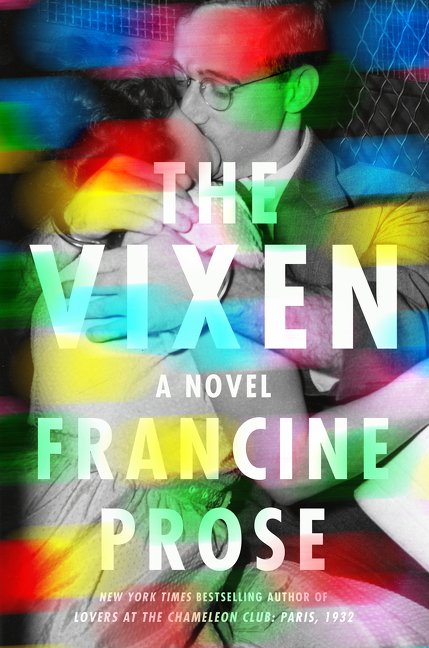

In the winter of 1954, I was assigned to edit a novel, The Vixen, the Patriot, and the Fanatic, a steamy bodice-ripper based on the Rosenberg case.

The previous year, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed for allegedly selling atomic secrets to the Russians. The horror of the electric chair and the chance that the couple were innocent had ignited outrage in this country and abroad. Protestors took to the streets in sympathy for the sweet-faced housewife whose only crime may have been typing a document for her brother, David Greenglass.

But according to the manuscript that landed on my desk, the Rosenbergs (in the novel, the Rosensteins) were Communist traitors, guilty of espionage and treason, eager to soak their hands in the blood of the millions who would die because of their crime.

The Vixen, the Patriot, and the Fanatic, Anya Partridge’s debut novel, portrayed the Rosensteins as cold-blooded spies, masterminding a vast conspiracy to destroy the American way of life. Esther Rosenstein was a calculating seductress, an amoral Mata Hari who used her beauty and her irresistible sex appeal to dominate her impotent husband and lure a string of powerful men into putting the free world at risk of nuclear Armageddon.

It was strange that I, of all the young editors in New York, should have been chosen to work on that book. My mother grew up on the Lower East Side, in the same tenement building as Ethel—Ethel Greenglass then. They went to the same high school. They hadn’t been close, but history had turned Ethel, in my mother’s eyes, into a beloved friend, almost a family member, the victim of a state-sanctioned public murder. Perhaps my mother’s sympathy was unconsciously spiked by our natural human desire for proximity to the famous.

My being assigned The Vixen was, I thought, pure coincidence. No one at work knew about the family connection. The only person who bridged the distant worlds of home and office was my uncle Madison Putnam, the distinguished literary critic and public intellectual, who had used his influence to arrange my job. If he knew that his sister-in-law had been Ethel’s neighbor and classmate, he would never have said so.

Joseph McCarthy, the senator from Wisconsin, was still conducting investigations, accusing people of being Communists plotting to destroy our freedom. There were no trials, only hearings. McCarthy was the prosecutor, judge, and jury. To be accused was to be convicted. Once you appeared before the committee, your friends and coworkers shunned you. Most likely you lost your job. There were betrayals, divorces, suicides, early deaths brought on by panic about the future. Refusing to cooperate with the investigation could mean contempt citations and prison. The cooperating witnesses who agreed to “name names” were despised by their more courageous and principled colleagues.

You didn’t mention someone you knew in the same sentence as a Russian spy. You definitely didn’t admit that your mother or wife or sister-in-law grew up with the woman who committed the Crime of the Century. Those were not the celebrities whose names anyone dropped, not unless you wanted the FBI knocking on your door. If someone found out that Mom had known Ethel, my father could have been fired from his job managing the sporting goods store, and Mom would likely have been barred from going back to teaching when the doctors cured her migraines.

A tawdry romance loosely based on the Rosenberg case, The Vixen, the Patriot, and the Fanatic was intended to be an international bestseller. It was not the sort of book that would normally ever appear under the imprint of the distinguished firm of Landry, Landry and Bartlett.

Landry, Landry and Bartlett published literary fiction, historical biographies, and poetry collections, mostly by established poets. The company was founded just after the Second World War, though it seemed to have been fashioned after an older, more venerable model: a long-established family firm. Since the retirement of its ailing co-founder Preston Bartlett III, one heard rumors—whispers, really— that its finances were shaky and its future uncertain, rumors that my uncle seemed delighted to pass on.

The hope was that the money The Vixen generated might allow us to continue to publish the serious literature for which we were known and respected, and which rarely turned a profit. It was made clear to me that publishing a purely commercial, second-rate novel was a devil’s bargain, but we had no choice. It was a bargain and a choice that our director, Warren Landry, was willing to make.

*

Perhaps this is the point to say that, at that time, my life seemed to me to have been built upon a series of lies. Not flat-out lies, but lies of omission, withheld information, uncorrected misunderstandings. Many young people feel this way. Some people feel it all their lives.

The first lie was the lie of my name. Simon Putnam wasn’t the name of a Jewish guy from Coney Island. It was the name of a Puritan preacher condemning Jewish guys from Coney Island to eternal hell-fire and damnation. My father’s last name, my last name, was the prank of an immigration official who, on Thanksgiving Day, in honor of the holiday, gave each new arrival—among them my grandfather—the surname of a Mayflower pilgrim. Since then I have met other descendants of immigrants who landed in Boston during the brief tenure of the patriotic customs officer. Brodsky became Bradstreet, Di Palo became Page, Maslin became Mather. Welcome to America!

And Simon? What about Simon? My mother’s father’s name was Shimon. The translation was imperfect. In the Old Testament, Simon was one of the brothers who tried to murder Joseph.

I hadn’t (or maybe I had) intended to compound these misapprehensions by writing what turned out to be my Harvard admissions essay about the great Puritan sermon, Jonathan Edwards’s “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” delivered in Massachusetts, in 1741. My English teacher, Miss Singer, assigned us to write about something that moved us. Moved, I assumed, could mean frightened. I wanted to write about Dracula, but my mother paged through my American literature textbook and told me to read the Puritans if I wanted to understand our country.

I wrote about Edwards’s faith that God wanted him to terrify his congregation by describing the vengeance that the deity planned to take on the wicked unbelieving Israelites. It seemed unnecessary to mention that I was one of the sinners whom God planned to throw into the fire. I was afraid that my personal relation to the material might appear to skew my reading of this literary masterpiece.

I had no idea that Miss Singer would send my essay to a friend who worked in the Harvard admissions office. Did Harvard know whom they were admitting? Perhaps the committee imagined that Simon Putnam was a lost Puritan lamb, strayed from the flock and stranded in Brooklyn, a lamb they awarded a full scholarship to bring back into the fold. That Simon Putnam, the prodigal Pilgrim son, was a suit I was trying on, a skin I would stretch and struggle to fit, until I realized, with relief, that it never would.

The Holocaust had taught us: No matter what you believed or didn’t, the Nazis knew who was Jewish. They will always find us, whoever the next they would be. It was not only pointless but wrong—a sin against the six million dead—to deny one’s heritage, though my uncle Madison had done a remarkable job of erasing his class, religious, and ethnic background. I tried not to think about the sin I was half committing as I half pretended to come from a family that was nothing like my family, from a place far from Coney Island. If someone asked me if I was Jewish, I would have said yes, but why would anyone ask Simon Putnam, with his Viking-blond hair and blue eyes? My looks were the result of some recessive gene, or, as my mother said, perhaps some Cossack who rode through a great-great-grandmother’s village.

*

When Harvard ended, in June, I’d returned to Brooklyn without having acquired one useful contact or skill my parents had hoped would be conferred on me, along with my diploma. Another lie of omission: My mother and father were astonished to learn that I had majored in Folklore and Mythology. What kind of subject was that? What had I learned in four years that could be useful to me or anyone else? How could eight semesters of fairy tales prepare me for a career?

Freshman year, I’d taken Professor Robertson Crowley’s popular course, “Mermaids and Talking Reindeer,” because it was a funny title and it sounded easy. After a few weeks, I knew that the tales Crowley collected and his theories about them were what I wanted to study. Handed down over generations, these narratives were not only enthralling but also seemed to me to reveal something deep and mysterious about experience, about nature, about our species, about what it meant to tell a story—what it meant to be human. I wanted to know what Crowley knew, though I wasn’t brave or hardy enough to live among the reindeer herders, shamans, and cave-dwelling witches who’d been his informants. I wanted to be like Crowley more than I wanted to sit on the Supreme Court or win the Nobel Prize or do any of the things my parents dreamed I might do.

Despite everything I have learned since, I can still remember my excitement as I listened to Crowley’s lectures. I felt that I was hearing the answer to a question that I hadn’t known enough to ask. That feeling was a little like falling in love, though, never having fallen in love, I didn’t recognize the emotions that went with it.

By the time I took his class, Crowley was too old for adventure travel. He’d become a kind of Ivy League shaman. Later, he would become the academic guru for Timothy Leary and the LSD experimenters, and soon after that he was encouraged to retire.

Every Thursday morning, the long-white-haired, trim-white-bearded Crowley stood at the bottom of the amphitheater and, with his eyes squeezed shut, told us folktales in the stentorian tones of an Old Testament prophet. Many of these stories have stayed with me, stories about babies cursed at birth, brides turned into foxes, children raised by forest animals. Most were tales of deception, insult, and vengeance. Crowley told story after story, barely pausing between them. I loved the wildness, the plot turns, the delicate balance between the predictable and the surprising. I took elaborate notes.

I had found my direction.

At the start of the second lecture, Crowley told us, “The most important and overlooked difference between people and animals is the desire for revenge. Lions kill when they’re hungry, not to carry out some ancient blood feud that none of the lions can remember.”

He kept returning to the idea that revenge was an essential part of what makes us human. Lying went along with it, rooted deep in our psyches. He ran through lists of wily tricksters—Coyote, Scorpion, Fox—and of heroes, like Odysseus, who disguise themselves and cleverly deflect the enemy’s questions.

It was unsettling to take a course called “Mermaids and Talking Reindeer” that should have been called “Lying and Revenge.” But after a few classes we got used to all the murderous retribution: the reindeer trampling a man who’d killed a fawn, the mermaids drowning the fisherman who’d caught one of their own in his net, the feud between the Albanian sworn virgins and the rapist tribal chieftain. Crowley told so many stories that proved his theories that I began to question what I’d learned from my parents, which was that most human beings, not counting Nazis, sincerely want to be good.

What little I knew about revenge came from noir films and Shakespeare. What would make me want to kill? No one could predict how they’d react when a loved one was threatened or hurt, a home destroyed or stolen. But why would you perpetuate a feud that would doom your great-grandchildren to a future of violence and bloodshed?

I was more familiar with lying. How often had I told my parents that I’d spent the evening studying with my friends when the truth was that we’d ridden the Cyclone, again and again? Lying seemed unavoidable: social lies, little lies, lies of omission and misdirection. I wondered where I would draw the line, what lie I couldn’t tell, and I wondered when and how my limits would be tested.

I wrote my final paper for Crowley’s course on a tale told by the Swamp Cree nation, about a Windigo, a monster with a sweet tooth and a skeleton made of ice. In revenge for some insult, the Windigo uproots huge trees and tosses them around, killing the animals that the Cree depend on for survival. Finally the people lure the monster to their village with the promise of a cache of honey, and the warriors kill it with copper spears, heated in the fire and thrust into the Windigo’s chest, melting its icy heart and bones.

Lying, revenge, the story had everything. I wrote my essay in a fever heat even as I used words I would never normally use, translating myself into a foreign language, the language of academia, clotted with phrases like thus, nevertheless we see, and consequently it would seem, with words like deem, furthermore, and adjudge. The A that I received was my only one that semester, thus further strengthening my desire to study with Robertson Crowley.

At the end of the term, students called on Crowley for individual conferences, and he advised us on what we might want to focus on, at Harvard.

He stood to greet me as I entered his office, deep in the stacks of Widener Library. The furry hangings and snarling wooden masks with bulging eyeballs and bloody incisors reminded me of the mechanical clowns and Cyclops outside the Coney Island dark rides. I was ashamed of myself for recalling something so vulgar in that hallowed place of learning, in the office that I so wanted to be mine someday.

Crowley said, “Mr. Putnam. Good work. While you are at college you must study ‘The Burning.’”

“Great idea,” I said. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. Now will you please send in the next student?” I’d watched other students go into his office. Several had stayed much longer. I tried not to dwell on this or to wonder if I’d failed in some way, and if his friendly compliment and his advice were a way of rushing me out. I chose to ignore this distressing memory when, three years later, I asked Crowley for a graduate school recommendation.

Leaving Crowley’s office, I’d had no idea what “The Burning” was. It took all my courage to ask his pretty assistant, who later became a respected anthropologist and disappeared in the Guatemalan highlands in the 1980s. I pretended to know what he could have meant, but . . .

“Obviously,” she said, “Njal’s Saga. The only thing he could mean.”

I read the saga that summer. When I got to the end, I reread it. The world it portrayed was merciless and violent, but beautiful, like a film or a dream, a world of cold fog rising off the ice, of mists that engulfed you and separated you from your companions. I read other sagas, but I kept going back to that one. Why did I like it best? I wrote my senior thesis about it, as if the answer would emerge if I only read the text more closely and wrote about it at greater length and depth.

Running through the thirteenth-century saga is a long and vicious dispute between Njal and a man named Flosi. This kinsman kills that kinsman; one soldier kills another. Each death is payback, brutal death repaid by brutal death. Under attack, Njal takes refuge with his clan, in the family longhouse. Flosi’s men surround them. They let the women and children go, but when one of Njal’s sons tries to sneak out, disguised as a woman, he is recognized and beheaded. Flosi’s men set the building on fire. Eleven people die. Near the end, Njal’s surviving son kills a man for mocking his brother’s failed escape.

I wrote about revenge. I had to. Crowley was on my committee. I wrote about truth and honor, about masculinity, and how even sworn enemies knew that it was evil to slander the innocent dead. I had a scholar’s curiosity, a deep love for my subject. I loved research. I loved the way that one text led me to another, the way that each book suggested the next I needed to read.

After my thesis was accepted with high honors, I passed Crowley in the hall, and he said, “Congratulations.”

Later I went to see him after I’d been rejected by the University of Chicago. I thought he might know why. I knew it was pathetic to ask, but I couldn’t help it.

He seemed not to remember me. He nodded as he listened to my story, which took two sentences to tell.

He said, “I’m sorry. Good luck.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Vixen by Francine Prose. Excerpted with the permission of Harper. Copyright © 2021 by Francine Prose.