Kay Ryan on the Preposterous Beauty of Gerard Manley Hopkins

One Legendary Poet Analyzes Another

Spring and Fall

to a young child

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow’s springs are the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

*

As with so much Hopkins, this poem is preposterously beautiful. Its difficult syntax compels its reader to submit to its world almost immediately. Well, even before we get to the improbable “man, you—can you?” the neologisms have altered our minds: “Goldengrove unleaving.” I don’t know if Goldengrove is an actual stand of deciduous trees or not; I vote for Hopkins having invented this tract name to carry all the beauty of loss in a single word. Hear the sounds of “go, go” in Goldengrove; simply to invoke a golden grove is to say it is going. The poem reminds me of Frost’s “Nothing Gold Can Stay”—both poems so immense and sad to the point of peace. There is no escape from loss—unless the pure beauty of the poems provides one, as it does for me.

But back to “unleaving.” The new word is generated, I would imagine, by the unstudied opening line, “Margaret, are you grieving?” That’s something Hopkins might have written quickly, and it would have given him—always ready to forge new words—the rhyming word “unleaving,” which of course just means ordinary losing-its-leaves, and is a convenience. But it also hap- pens to operate as a pun on leaving’s other sense—going away. Here it is unleaving, of course, but the “leave,” like the “go” in Goldengrove, is planted in our mind’s ear.

This couplet, “Margaret, are you grieving / Over Goldengrove unleaving?” is as easy on the tongue as the following couplet is impossible: “Leaves, like the things of man, you / With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?” Let me just say that my hat is off to Hopkins for this. I’ve never really examined this poem before, hav- ing submitted to it utterly at the age of nineteen. This is the point at which Hopkins compels us to take off our clothes and enter his river. It is wildly strained, forced, manipulated, and—we already feel—worth it. If we are not compelled to submit in some way to a poem it cannot change us. That makes perfect sense, now that I’ve written it, but I don’t think I ever thought of it before.

So this is not a tormented couplet that we forgive for the greater good of the poem, averting our eyes discreetly from that howler, “man, you—can you?”; this is the couplet of our entrance, of our acceptance of Hopkins’s terms. He can continue from here. He has made aesthetic decisions so aggressive—the “you” after “man” hanging at the end of line three; the postponement of “can you” (with the help of lots of commas) to the end of line four—which just in sorting out the sense sends the mind rummaging back through the couplet, while at the same time moving forward. We’re converts here, or we’ve quit.

But let me pause at the pair of words “fresh thoughts” referring to the grieving Margaret. Hopkins is surprised at Margaret’s grief at the falling of the leaves of Goldengrove. How can she care for them, or for “the things of man”? Aren’t we at some early point immune to the knowledge of loss? I wonder if the little prick of added sadness when Hopkins sees that Margaret is not immune wasn’t itself what provoked this fifteen-line poem dropping all the leaves in the world.

All the parts of a poem exist as a sort of plasma, simultaneously apprehended, existing in the mind all at once, as soon as we have become familiar with them.

It is so interesting how the first few lines of a poem do the hard work. We are now prepared for the development of the feeling of division in these next two couplets. First, division within the self—that is, Hopkins’s own loss of his original knowledge of loss, which always comes in a specific circumstance, as it has for Margaret seeing Goldengrove unleaving. Hopkins feels the separation of his child self from his older self. I feel, although I don’t see exactly what’s doing it, something like the pain of cell division, with its strange stretching and weird afflictions.

A chill and distance enter lines five to eight. You will grow accustomed to things like this, the lines say. By now we are used to the rhymes, the syntactical inversions (worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie) and the new words he’s created. The compressions of two words into one—wanwood; leafmeal—don’t cause a ripple; they’re perfect for something that makes natural and emotional sense to us. Wanwood: vivid Goldengroves reduced to colorlessness; and the knowledge arrives on the little blowing-out w’s—worlds of wanwood—the color is blown off. Leafmeal: no longer leaves, just as no longer golden. The leaves are ground to meal. They aren’t crisp and rattly and gold; they are a pale paste. We see this in crushed leaves, how they go grey, how they are undone. And in ourselves, how brightness is so bafflingly lost and how edgeless (worlds of wanwood) the diminishment is. Here in line nine is the turn of this not-sonnet: “And yet you will weep and know why.” Now the separation of Hopkins from the young girl is reversed. Hopkins embraces her (and with her, his own child self ) as he inducts her into the endlessness, the bottomless- ness of loss. It is magnificently beautiful, the oneness Hopkins paradoxically generates among all of us in describing how we will lose one another. Here is the lesson: You’re not wrong to weep, and “will weep.” All sorrow comes from the same spring.

Now comes the achievement of the unachievable when Hopkins’s syntax goes all squirrely with the “nor, no, nor” thing. This is useful, I would even say necessary, this incomprehensibility of the grammar. We do read it, and we are moved out of our grammar into something that could be spiritual if there were a spirit beyond this readiness to know the spiritual. But the great openness generated by these strange words is absolutely smacked; there is nothing to receive the spiritual vulnerability. This is emphatically not a Christian poem; it is as dark as Frost. All that our greatest sensors, our farthest probes, are met with is in the final couplet: “It is the blight man was born for, / It is Margaret you mourn for.” The world “blight” is a thrilling achievement. It incinerates, it blackens, it curses and damns. All will die, and there is no consolation. You are mourning for yourself, and when I say you, Margaret, I mean me (says Hopkins). See how Hopkins has increased the tenderness in this lesson: “Now no matter, child, the name.” His voice is holding us tenderly to him, instructing us: he bewitches us with the sorcery of “nor,” “no,” “nor,” then he clubs us with “blight.” If the word had been, say, “fate”—“It is the fate man was born for”—I think the whole poem would collapse. It is the word “blight”—absolute, harsh, and natural; a natural evil, something that wipes out what was living—that charges the poem backwards.

And that is one of the particular beauties of poetry as opposed to, say, the novel. A poem really has no beginning and end, although it does appear to. All the parts of a poem exist as a sort of plasma, simultaneously apprehended, existing in the mind all at once, as soon as we have become familiar with them. The word “blight” constantly and forever charges every word in the poem, shores every word in the poem. It is Indra’s net, everywhere is the center, reflecting all. This great capacity of poetry is seldom so well exercised as it is here. The fact that the mind can move around in a poem—is asked to do this—is why poetry is considered the supreme art. Poetry is the shape and size of the mind. It works the way the mind works. It is deeply compatible with whatever it is we are. We dissolve in it; it dissolves in us.

This poem, “Spring and Fall,” has reminded me of why I want to continue to try to write poems. I am grateful to it.

*

Postscript

In such great poems, there is always so much more left to say when you have said what you thought you wanted to say. Now I am thinking of Hopkins’s beginning and ending with “Margaret” and the great transformation of what we come to understand to be Margaret. At the beginning, Margaret is a child, seeing something sad, addressed by an older person. She is discrete, separate. By the end it is difficult to express all that Margaret is: she is still one—one person, who will die, one person who must suffer the knowledge that all will be lost and she will lose herself. And yet it is this retention of Margaret’s identity by name that creates the greatest poignancy: not, Hopkins could have said, all will be lost, but Margaret will be lost. In keeping it singular in this way each single living thing is a jewel in Indra’s net. Each self contains the universe. Each self must experience its extinction. Each self is tender toward itself. Hopkins is Margaret. We are Margaret; the unassuageable grief is not that we will all die but that Margaret will die with the knowledge that there are only Margarets . . . some of whom are so young they don’t yet know.

__________________________________

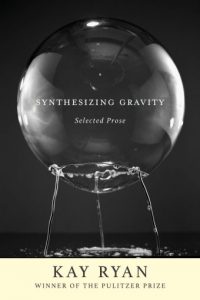

From Synthesizing Gravity by Kay Ryan. Copyright © 2020 by Kay Ryan. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Grove Atlantic.

Kay Ryan

Kay Ryan was born in California in 1945. She has published nine books of poetry, including Elephant Rocks (1996), Say Uncle (2000), The Niagara River (2005), The Best of It: New and Selected Poems (2010), and Erratic Facts (2015), all from Grove Press. The Best of It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2011. She served as Poet Laureate of the United States from 2008 to 2010. Of “Some Transcendent Addiction to the Useless,” Ryan writes: “I cannot hope to attain the transcendent uselessness George Steiner attributes only to ‘a handful of human beings’ (Mozart for one), but perhaps I will have occasionally managed the undoing of a few things that needed it. This poem hopes that.”