Julian Alexander on 50 Cent, Marlon James, and What Makes a Good Cover

Yahdon Israel interviews the Graphic Designer about Creating a Visual Language

Julian Alexander is a Grammy award-winning designer perhaps most famous for creating the album cover for 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Trying. He’s also the founder of the design firm Slang Inc., which provides print graphics, retail and commercial environmental design, brand identity, product development and design, visual art direction, and advertising. Yahdon Israel recently sat down with Alexander to finally answer the question: Should you judge a book by its cover?

Yahdon Israel: What were some of your earliest interactions with book covers?

Julian Alexander: They weren’t book covers, but record covers. Growing up my father had a record collection. I don’t think I was allowed to play them. There was never a discussion where my father said Don’t touch my records. I just knew I couldn’t because of the fear that I’d scratch them. So I would sit there and look at the covers. I would want to hear them based on whether I liked the cover or not. Parliament had spaceships, and colorful hair. I wanted to hear what that sounded like. As opposed to… my father had George Benson records. They were cool. But I’m looking at Rick James and Parliament, and other things because the covers were exciting.

YI: Rick James in thigh-high boots, dressed like a wrestler.

JA: Yeah, exactly. And it wasn’t that I looked at them and saw myself. I didn’t want to dress like that. I didn’t want to do that. But I wanted to hear what that person was talking about. If this looks this way, what does it sound like. Those singular experiences have always been important to me.

My career [as a visual artist] brought me, strangely enough—or maybe not strangely enough—to do some record covers. At the time when I was looking at those album covers, I didn’t see that as an option. It wasn’t something that I aspired to do. It was something I enjoyed. When I got to learn what graphic design was, that seemed like a really great path to go down because it’s ubiquitous. You go to a grocery store and you’re in an environment where there’s graphic design. Except for the vegetables. You know what I mean? It’s all design.

It’s why, as a kid, you want Froot Loops instead of generic cereal—because it has a cartoon on the character. It connects to you in certain way. Later on, I started designing covers; creating artwork and wanting to design covers.

Every Tuesday I used to go to the record store and buy records. I knew what was coming out, but sometimes if I ain’t see something I wanted I would just wander around looking for something that looked cool. If I wanted to try a different genre of music, I would look at the covers. Sometimes it worked out really well; other times it was hot garbage. That has translated to books in a certain way. And it’s because I value the power of artwork. If you are making a book cover, you’re supposed to communicate what that book is about. Book covers have the ability to be more powerful than an album cover or a movie poster.

YI: Man, let’s go into that.

JA: On an album, I’m hearing your voice; you’re telling your story. You’re controlling what I hear. With a movie poster, these are often images from the movie. I’m going to see it. It has a visual companion. When we read a book, when we read characters, we’re not actually seeing that person. When they describe a place, it’s all in our heads. The only visual reference you have with a book is the cover. So I feel like it sets the whole tone for what the experience will be.

That’s why I say it might resonate more. Today album packaging is kind of incidental because each song may have a video. You will get visuals that go along with the songs that may or may not be in line with the cover. But with a book, the cover’s the only visual you get. Unless they make a movie later on, and then you’re comparing that to the images you had in your head.

YI: What are some of the things you look for in covers? Have you reached a point where you’ve developed a language for what grabs you about a cover?

JA: There’s a book—A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James. I want to read that book because of the cover. I have a picture of the cover in my phone. I often go to bookstores and just take pictures of the covers. There’s a website dedicated to book covers, and I look at it for design. If you can intrigue me with design, you got me.

I make visuals. I’m attracted to them. Some people could look at that as superficial. But it’s what motivates me. It communicates to me quickly. If the cover truly does represent the book, which is what the purpose of a cover should be, then it’s an art form that supports another art form.

But a book could also be different. If I don’t like the cover, but you tell me you like the book, and I know we have similar tastes, I can look past the design if it’s not up to snuff.

YI: But in a sense, the person who suggests the book becomes another cover for the book. An alternate cover. You’re willing to look past one cover to see another. I consider book covers as a way to think about the work. It gives you a visual language to think about the work. For me, the reason I have been so attracted to visuals is because I didn’t like reading growing up. When I did read, it had to have a lot of pictures. That’s part of how I learned how to read—whatever word or words I didn’t know, they picture would help me figure out what I was missing on the page. I wouldn’t know exactly what those words were, but the pictures brought me closer to some level of understanding.

A lot of people talk about reading as something only textual. But I’m a heavy reader of signs and signifiers, of words and their contextual meanings. You look at the cover for the Autobiography of Malcolm X, where there are several portraits of his face on the cover, and I read that as a visual representation of the many ways in which he existed over various times in his life. The dimensions. That gives me a way to engage with what I’m about to read.

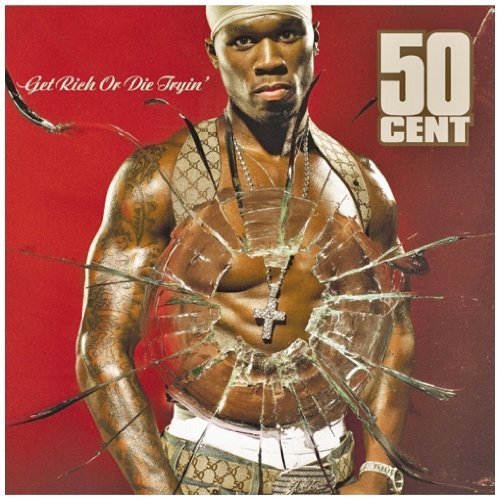

Being a graphic designer, of course, you know this. You’ve created a lot of visuals for albums that, before I even popped the CDs in, were telling me about the stakes, or some of them. When Get Rich or Die Tryin’ came out, I was 12. When I saw that album cover—with 50 Cent wearing the Gucci gun straps, and the bullet hole through the cover—I was like “this is about to be the most gangster shit I’ve ever heard.” Then I put the CD in, and it delivered.

So tell me how you were able to marry that image to the content of the album.

JA: 50 and I had known each other for a couple of years prior to that album coming out. I was his art director when he was signed to Columbia—and I designed his Power of the Dollar album that never came out. But I completed that album. I did the singles from it. He and I built a relationship. We had a good rapport. We were in contact. He liked what I did to the point where he said, “Wherever I go, I want you to do my artwork.”

So when he finished Get Rich or Die Tryin’, he called me. I went to his grandmother’s house in Queens and he played the album for me. So I knew what the album sounded like before we even started. I already understood what people would now call the “brand.” But I knew him—where he was coming from, what he was representing. He had some ideas of the cover. And we worked together to refine that. It’s a collaborative thing.

As an art director, my role is to make sure I get something to the point where it’s meeting the need and the vision I have for it. Everyone has ideas—and a certain level of vision—but as the director, I am ultimately responsible for executing that vision.

Right now if you look at that album cover, in the middle of the bullet hole is the diamond cross he’s wearing. When the photographer started shooting it, it was framed differently so that his head was in the bullet hole. And I was like, “Nah.” In that moment I looked at the bullet hole like a metaphor. Here’s a person who survived being shot multiple times but—this is going to sound cheesy—through the grace of God he survived because he’s wearing the cross.

I always want to make sure there’s a clear but complex message. I’m looking at what the concept is. I’m looking at the composition. Then I’m looking at typography, thinking, “What kind of typography can I put on here that will help tell this story?” 50’s album has a script font. It’s a type treatment that feels a lot more elegant than what the content of the album is describing. It’s about this contrast. He has a holster on, but it’s a Gucci holster. There’s a belt buckle that’s flooded with diamonds. It’s bringing this balance. Because you’re telling this really gritty story, you’re talking about violence, but at the same time the album is named Get Rich or Die Tryin’. It’s all about the pursuit of money and power. And we’re representing it through the typography, through a certain level of elegance that’s a contrast to the griminess.

YI: I’ve always enjoyed when a writer provides language for something I’m familiar with because it gives me another way to see it. In On Michael Jackson, Margo Jefferson described, move for move, Michael Jackson’s 1983 Motown performance where he first did the moonwalk. The writing was done with such precision that I actually decided to watch the performance as I read it. I had only ever seen clips of that performance, I had never seen the whole thing. So to be able to witness that performance along with a language to understand it was one of the best experiences for me. And it also made me think: “How many times did Jefferson have to watch that to develop a language for it?” I say all this to ask you: what’s your process for developing a language for the projects you work on? Do you storyboard it, or just go in blindly?

JA: Now I work a bit differently. Before, I was just describing it. Talking about what I envisioned with the people I was working with. I would try to stack the deck to get what I wanted. If I was art directing a photo shoot, I would choose the photographer whose vision I felt was in line with my vision. If I was shooting a portrait of someone, I would not go to someone who shoots landscapes. I would build the team that I needed to get the outcome I wanted. That’s how I used to approach it, through dialogue.

If I tell you to think of a box, none of us are going to think of exactly the same thing. So now I help the process along by building mood boards. And it helps to make sure we’re all on the same page going forward. I functioned well without them. But the mood boards have streamlined the process. It gets us to the point quicker where we can make sure we’re understanding each other. And they’re not literal. I’ll never show anyone a mood board and say This is what I want to do. It’s a general space. This is kind of what the box looks like. We’re going to make the box together.

YI: So, then, would you say that a book cover is a conversation with the work, text?

JA: I think of covers as the summary of a text. I don’t think of it as a conversation because it’s not interactive. Conversation is dialogue. Cover are not you say this, and I say that. They’re more like: you were talking and I paraphrased. That’s it. Covers boil a text down to its important elements.

YI: When did you know you wanted to be a graphic designer?

JA: I didn’t know what graphic design was. And I didn’t know what I wanted to do when I finished high school. I went to UConn. I’m a first-generation American. I knew I had to go to college because I’m the oldest. So I went to UConn as a liberal arts major. I still don’t know what liberal arts means, but it sounded generally cool. I had an art teacher who would have us draw still life images of bell peppers. She thought the shapes of them were central. We had other assignments, but I remember this one specifically because we were drawing on an 18″ x 24″ pad.

Everyone drew their bell pepper in the middle. I made a frame on mine and drew the bell pepper in the bottom corner, hallway off. It just made it more interesting to me. The teacher saw that and said, “I think you’d be good at graphic design.” I was like, “What’s that?”

She told me what graphic design was, and she also helped me put together a portfolio to apply to art schools. Graphic design seemed safer to me than just wanting to be a fine artist. With graphic design, I saw it as, “I could be an artist with a job.” It was very practical. Now I’m bucking that, but at that point, the practicality was key.

YI: Since becoming a graphic designer, what projects stand out in your mind?

JA: The Miles Davis box set I worked on stands out because of what it represents in my career. I’m really proud of the work. And it’s Miles Davis. So I felt a great sense of responsibility. I didn’t want to fuck up an impeccable body of work. Also, I didn’t have the ability to talk to him. A lot of my creative process is sitting down with an artist and talking with them. While I did have the music that was going into the collection, I wouldn’t listen to it until after it came out. Because if I ain’t like it, I didn’t want that to influence my work. Instead, I read Quincy Troupe’s biography on Davis, Miles and Me, to get a sense of who he was. And then I designed it.

The first time I ever listened to the box set is when I got the final product, with everything completed.

YI: Did you feel like the visuals synced with the what you read of the biography and the music?

JA: Well, the cover had existed already. The box set collection is called The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions. Miles released that album at some point during the early 1970s. I was born in ’74. For the style of the imagery, I thought about wallpaper that had been in my house. Just what the energy was around that time. And that’s where I drew inspiration from. That and the Troupe biography. The cover is the one from the original album, but outside of that, the box set is all me.

I worked with the product manager and pulled photos of Miles from around this time. So I could respond to those images in a way which felt historically correct. The packaging includes a 120-page book and five CDs. It has this metal binding. The finish on it looks like the horn he used to record this album. And the typeface is called heavyweight; it’s inspired by old boxing posters. Jack Johnson was a boxer. So again, I just wanted to connect the dots.

YI: We keep circling back to fonts as having their own meanings and histories. How do you know which fonts work, and which ones don’t?

JA: I love graffiti. As a kid, part of the reason I wanted to come to New York—I’m from Connecticut—is to paint trains. I thought that’s what I wanted to do. That was the life goal. And it’s interesting because I think about it now and it was a very pure aspiration. I had a visceral response to that. I love letters and forms.

I think letters evoke a feeling. They set a tone—and you can easily see when it goes wrong. In the NBA, after Eric Garner was killed, all these players wore the “I Can’t Breathe” shirts, but they were using comic sans. That’s the font that’s used in comic books. So I looked at it like, “Why would you use that font? That’s the polar opposite of what you’re saying.” To me these things should resonate. To some people it’s just about what the words say. But fonts and lettering are literally the foundation for the visual representation of language.

YI: What do you think about that idea of not judging a book by its cover?

JA: I don’t think you should judge a book without reading it; books are intended to be read. But I do think that a cover can do an excellent job of getting you to give the book a chance. Am I supposed to read every book to see which one I like? You gotta start somewhere.

I feel that the cover can be more honest than the blurbs on the back. It’s supposed to be. I don’t know if it is. When I make art, I’m not looking at what I think is going to sell. I’m thinking of making the best piece of art I can. The intentions behind the cover should represent the book.

YI: Do you think blurbs take away from a book?

JA: Nah. I realize that the blurbs have as much value to someone else as the covers have to me. Some people don’t care about the cover at all. They care about what this editor or literary figure had to say about it. So I understand that my point of view is not the supreme point of view. It’s just a point of view.