A Very Rare Book by One of America’s All-Time Great Athletes

Visiting Jim Thorpe's $10,000 History of the Olympics

I wouldn’t trust a man who wasn’t a little sentimental about the Olympics, or the Summer Olympics anyhow. There’s a great deal about the Games to resent—the Coca Cola sponsored pomp, the sanctimonious bureaucrats, the police round-ups, and the displacement of the host cities’ poor, to name just a few. But the Summer Games are held once every four years, and then there are the old-fashioned ideas about unity and sportsmanship and the innocence of youth at play, which are relatively simple things to subscribe to on an August evening, when the local news is done and Bob Costas comes on the air with his boyish looks, speaking in paragraphs.

Sentimentality, in fact, is the Olympics’ stock-in-trade, and so the Games produce a tremendous number of mementoes and collectibles, mostly of the pins-and-coins variety, but also more exotic fare, like the gold shoes Michael Johnson wore in 1996 in Atlanta, or one of the silver-and-birch torches that lit the 1952 Games in Helsinki.

And then there are the books. Thousands and thousands of books have been written on the subject of the Games, but only a few have transcended the workaday literary world to become bona fide collector’s items. For reasons that remain a mystery to me, although I suppose they have to do with that sentimental streak I mentioned before, I recently set out to find a copy of the most rare and valuable of them all: Jim Thorpe’s History of the Olympic Games. Now, according to Rare Books Digest, there may be some disputing which is the most coveted Olympics book, but the two other contenders are The Official Report of the XI Olympic Games, by Wilhelm Limpert-Verlag and Leni Riefenstahl’s Schonheit im Olympischen Kampf, both of which were produced in connection with the 1936 Games, in Hitler’s Berlin. Seeing as I have no desire to travel to a German museum, or to delve into the world of Nazi memorabilia trading on the eastern US seaboard, and since the rare books trade is inherently subjective, and a given specimen is only as valuable as the intensity of the mania that drives a collector to posses it, I decided I was well within rights to declare Thorpe the winner, and to go about paying that legendary man a small homage.

* * * *

Jim Thorpe, for those who aren’t familiar with the name, was the greatest athlete who ever lived. That’s the lore, anyway. Personally, I’m inclined to believe it.

Thorpe was born in 1888 in Indian Territory, near the North Fork River in Oklahoma, and brought up within the Sac and Fox tribe. He was educated at “Indian boarding schools” and eventually ended up at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where he first got serious about athletics. He ran track and played football for Pop Warner and beat the mighty Harvard team 18-15 and won the national ballroom dancing crown, because it was there to be won. In 1912, he went to Celtic Park in Queens and earned a spot on the US Track & Field team assembling for the upcoming Games in Stockholm. With relatively little formal experience in many of the individual events, Thorpe won gold in the decathlon and the pentathlon. He set records in short and long distance races that would hold for decades. He won the high jump in borrowed shoes, after his were lost. King Gustav of Sweden, the host of the Games, famously declared Thorpe the “world’s greatest athlete” and said it was an honor to shake his hand. Thorpe replied, “Thanks, king.” Back in the States, he went on to play professional baseball for the New York Giants and football for the Canton Bulldogs. In 1963, he was a member of the inaugural class voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. That is the shortest possible version of his athletic résumé. Thorpe was, unequivocally and without peer, the towering sports figure of the time.

But the Olympic glories were short-lived. In 1913, The Worcester Telegram (I’m sorry to report I’ve spent time in Worcester) broke a story revealing that before the Games, Thorpe played two summers of minor league baseball in Eastern Carolina. The job earned him $2 per game and cost him the “amateur” status that the AAU took so very seriously when the athlete in question was not white.

At the AAU’s urging, Thorpe was stripped of his medals and records. They wouldn’t be returned until 1983, and as the great Sally Jenkins pointed out in her article for Smithsonian Magazine celebrating the centennial of his Olympic achievement, Thorpe has never been recognized as sole champion of the events he rightfully won.

Thorpe struggled to make a living after he was done with sports. He worked security jobs and dug ditches. He asked around Hollywood and joined the merchant marines.

In the middle of the Great Depression, Thorpe agreed to put his name on a history book intending to capitalize on Olympic excitement in the build-up to the 1932 Games in Los Angeles. The book was authored in collaboration with one Thomas F. Collison and put out by a vanity press called Wetzel Publishing Company, whose other claim to fame (loosely defined) is that it published the original version of Gadsby, a book written without using the letter ‘e’. Few copies were sold. Even fewer were preserved. By the time I got around to looking, there were three copies of Jim Thorpe’s History of the Olympics in circulation. The most valuable, listed at $10,000, was in possession of Mr. Jeffrey Bergman, resident of Fort Lee, New Jersey.

* * * *

Getting to Fort Lee, New Jersey on a Friday afternoon in summer isn’t an Olympic event, but it took a lot of effort nonetheless. By the time I arrived at Mr. Bergman’s apartment, I was sweating pretty vigorously and needed a few minutes to gather myself so that I wouldn’t drip on any of his collectibles. Mr. Bergman’s home is rich with collectibles. At one time, he and his father had a large bookstore, Womrath’s on 86th and Madison. Now he deals in rare books. “It’s a business,” Mr. Bergman said of his current trade, “I don’t get excited anymore.” He was wearing khaki shorts and a charcoal polo shirt. His cat wandered by. It was true, he didn’t look like a man prone to overexcitement, but then he showed me a first printing of Jules Verne’s 20 Leagues Under the Sea and a first edition of The Pickwick Papers that had belonged to Robert Gould Shaw, with a letter penned by Dickens tucked into the pages, and it seemed to me the both of us were having a pleasant time, business notwithstanding.

“Now let me show you what you came here to see.”

Mr. Bergman took Jim Thorpe’s History of the Olympics from its place on a bookshelf and handed it over to me. “They’re just things,” he said. “They’re meant to be read.”

He must have noticed that I was nervous holding the book. I was also holding a bottle of water. My hands are not very steady and I don’t have $10,000 to spare.

We went into the living room, where the light was better. The book’s cover is pea green, with a blue and yellow cross and the Olympic rings on the front. It has its original dust jacket. The jacket, according to Mr. Bergman, is a major factor in the book’s value. That’s a rule of the rare books trade. Another rule is to play coy when a guest asks questions about where you obtained the book, and when, and how much it cost.

I opened the cover and read from the beginning.

Chapter 1

The funeral of a hero, the wedding of a great soldier or leader, or a family reunion feast was the signal for a great display of athletic prowess among the men in that era known as the Homeric period of Greek history, arbitrarily established here as around 900 years before Christ walked in Judea.

There were a few sketches throughout the pages: for example, of young men in the nude chasing one another around with spears while aristocrats watch and applaud.

The story concludes with a chapter called “The City of Angels,” discussing Los Angeles in much the same tone as the book begins. I don’t know what I was expecting. Protest, maybe. Anger. Jim Thorpe railing against the AAU or the IOC or The Worcester Telegram or any of the institutions that had jobbed him in 1912-13.

But the book wasn’t a manifesto or even a memoir. It was a collectible.

“You missed the best part,” Mr. Bergman said. He turned to the presentation.

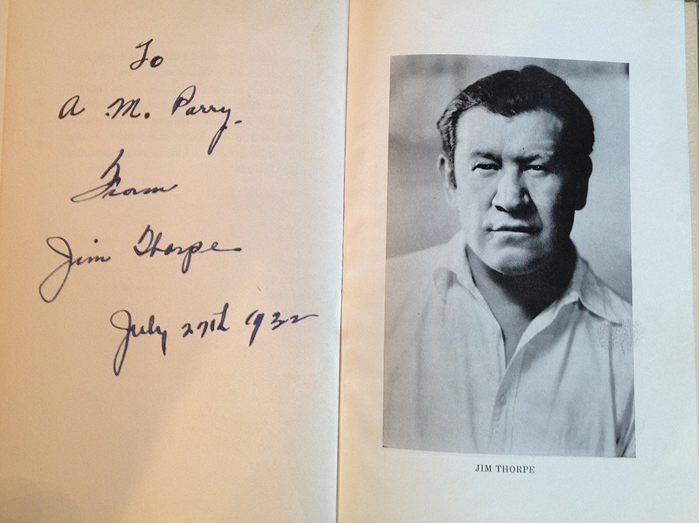

To A.M. Parry, From Jim Thorpe, July 27th, 1932.

Thorpe’s handwriting was beautiful, almost like calligraphy. When he was at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the young woman who taught his “commercial” classes—bookkeeping, stenography—was the poet Marianne Moore. Later in life, Moore used to praise Thorpe’s grace, his modesty, and his handwriting. She described it as “an old-fashioned Spencerian hand, very deliberate and elegant.”

“It’s the only one in the world with a presentation like that,” Mr. Bergman said.

I imagined Thorpe at his desk, signing copies of his History, then presenting them to friends and customers. There’s another copy of the book for sale from Whitmore Rare Books in Pasadena. It was signed by Thorpe, too, and then somebody took it around Olympic Village in Los Angeles and asked various athletes to add their signatures. About 50 did. Not a single one of them had handwriting like Thorpe’s.

“He had a very precise hand,” Mr. Bergman said.

I asked to take a picture, and Mr. Bergman agreed. My hand kept shaking, holding the phone and the book. It took several tries to get a decent image of the page. Fuck The Worcester Telegram, I thought, and for some reason that helped steady my grip.

After that, I thanked Mr. Bergman and he walked me down to the lobby.

* * * *

In 1932, when the book came out, Thorpe was living in Southern California. He couldn’t afford a ticket to the Los Angeles Games, but when Vice President Curtis, who also had American Indian ancestry, found out, he arranged for Thorpe to sit in the Presidential box. Twenty years later, again in Los Angeles, Warner Bros. made a movie about Thorpe’s life, starring Burt Lancaster. It was called Jim Thorpe: All-American, and the poster proclaimed, “He wore America’s heart over his!”, whatever that means. Lancaster later recalled that Thorpe was hired as a “football consultant” and that his wife tried to open a bar during the filming of the movie, but the producers weren’t pleased about it (Thorpe was a drinker), and they gave her a bit of money to shut the place down. Thorpe died three years after the movie came out.

His New York Times obituary began:

Jim Thorpe, the Indian whose exploits in football, baseball and track and field won him acclaim as one of the greatest athletes of all time, died today in his trailer home in suburban Lomita. His age was 64.

I can’t find any record of what The Worcester Telegram had to say.

* * * *

This is probably nothing, but it happened right after I left Mr. Bergman’s apartment and it feels to me like a part of the story. I was walking on the overpass across the New Jersey Turnpike, toward the George Washington Bridge bus depot, and ahead of me was a kid, maybe 13 or 14 years old, carrying a basketball. Two girls, about the same age, passed him by, going in the opposite direction. They looked like they were coming from the beach. The kid said to them, in a calm voice, “If you gave me your phone number, I could call you some time.” I don’t think he was directing it at one girl or the other but at the pair, or else it was just a rhetorical observation. One of the girls laughed and turned around and asked for the boy’s phone. She entered something in. It could have been her number or a fake or a message telling him to go to hell. Whatever it was, the boy looked happy about it.

The point, I suppose, is that the Olympics are coming up, and while the IOC and the international federations and the advertisers and the host city plutocrats getting fat off construction bids are indisputably loathsome, the athletes themselves are young. They come from all over the world and the things they do are astonishing to witness.

Call me sentimental, but I wish I could have seen Jim Thorpe up close.