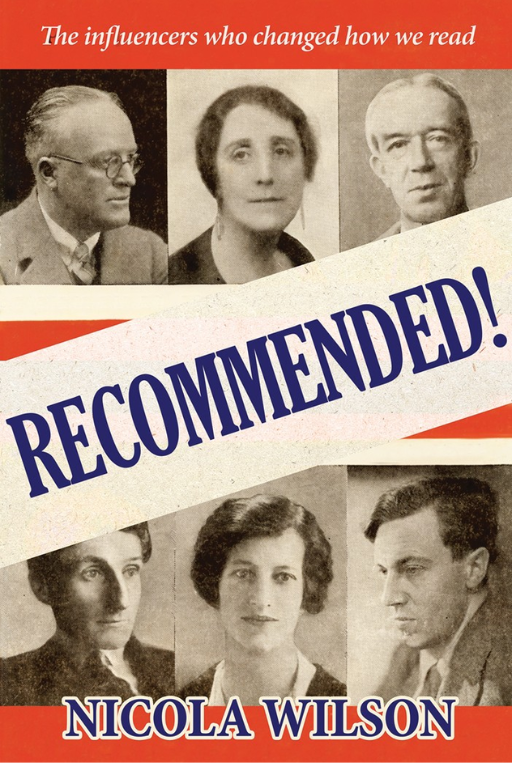

Judge, Critic, Saloniére: On Sylvia Lynd, One of the Great Literary Citizens of the 20th Century

Nicola Wilson on the Book Society, Hugh Walpole, and Lynd’s Overshadowed Author Career

On Thursday 9 July 1931, Sylvia Lynd hosted one of the biggest parties of her life. When the marriage of James Joyce and Nora Barnacle hit the papers (the Joyces had been living together since 1904 but had tried to keep it quiet), Sylvia decided to pull out all the stops. She roped in her grown-up daughters, now in their early twenties, to decorate the garden—hanging Chinese lanterns from the weeping ash and dotting night-lights in colored glass jars around the flowerbeds—and invited hordes of guests.

Sometime after midnight, they all squeezed into the drawing-room and Joyce sat at the piano, singing traditional Irish folk songs and reciting from his “Work in Progress” (later published as Finnegans Wake). It was one of Sylvia’s great successes.

Like many women who have created literary salons or used their wealth and privilege to put themselves at the center of things, Sylvia Lynd is now mainly remembered—if at all—for her weekly parties at 5 Keats Grove, Hampstead. “It was as a salonière that Sylvia loomed largest in what were then our too crowded and emphatic lives,” publisher Victor Gollancz, a friend and neighbour, wrote in his memoirs. “She was handsome, immensely energetic, ambitious, and a trifle ruthless and domineering.”

At her these gatherings—loud enough to annoy the neighbors—journalists, up-and-coming writers, and publishers could connect and carouse. In the early days of her marriage to Belfast-born journalist Robert Lynd, Sylvia’s set included Katherine Mansfield, John Middleton Murray, D.H. Lawrence, Rebecca West, and artist Mark Gertler (who Sylvia knew from the Slade School of Fine Art). Later, regulars included caricaturist Max Beerbohm, cartoonist David Low, Punch’s A.P. Herbert, and Sylvia’s best friend, novelist Rose Macaulay.

But Sylvia Lynd was also a professional full-time writer in her own right: a poet, novelist, essayist and critic. Her first book, The Chorus: A Tale of Love and Folly, was published in 1915, followed by volumes of verse and prose, three books of poetry (Macmillan brought out her Collected Poems in 1945), a novel, short stories, critical introductions and anthologies, plus a history of English Children for Collins’s wartime Britain in Pictures series.

Like many women who have created literary salons or used their wealth and privilege to put themselves at the center of things, Sylvia Lynd is now mainly remembered—if at all—for her weekly parties at 5 Keats Grove, Hampstead.

She regularly wrote articles and reviews for the papers; invited to represent “The Critic” in a series on contemporary publishing that ran in Time and Tide early 1930. In the early 1920s, Sylvia was literary advisor for Macmillan’s in New York, looking to place work from London that hadn’t found an American publisher. A decade later she was working as publisher’s reader for John Lane at the Bodley Head.

Most importantly, Sylvia Lynd helped sustain and promote a literary ecosystem. She was involved for many years with the Prix Femina-Vie Heureuse Anglais, a literary/translation prize established in the spirit of rapprochement where an English committee selected three books to be translated for a French audience, and vice versa.

As judge for the Book Society, Britain’s first celebrity book club, Lynd assessed manuscripts each month for over twenty years, shaping literary tastes and the books the club selected. She may not have intended to devote so much of her working life to service but she was a crucial intermediary in the literature sold and promoted by critics between the wars.

*

The Book Society was modeled on the American Book-of-the-Month Club, established 1926. Between 1929-1968 the Society selected one book each month to send out to its 10,000 plus members, transforming a title’s sales and global distribution (records show that publishers were keen to work with the club thanks to the additional sales and attention courtesy of what publisher Harold Raymond called “the Book Society bun”).

From the club’s beginnings, when chairman Hugh Walpole approached Sylvia with reverence (“I am very anxious that you should join us,” he wrote), Sylvia dominated in a committee of five, driving the decision-making and, in some cases, saving them from riskier choices. The deference other judges showed her was clear (in addition to the bestselling Walpole and Priestley, the selection committee included dramatist Clemence Dane, academic George Stuart Gordon, and, later, WWI poet Edmund Blunden and “Auden gang” poet Cecil Day-Lewis).

Sylvia’s talent for spotting the best new writing by other women didn’t necessarily help her own work.

Debating their first book-of-the-month early 1929, Sylvia got into a spat with Hugh over Joan Lowell’s The Cradle of the Deep (already a bestseller in the States thanks to the American Book-of-the-Month Club). Hugh was a fan, but Sylvia thought it too sensational, persuading him that Helen Beauclerk’s The Love of the Foolish Angel was a safer bet. Sylvia was proved right when The Cradle was exposed as a hoax (more fiction than autobiography) and their American counterpart had to offer members a refund.

When Sylvia missed a meeting (she struggled all her life with chronic ill-health), the judges could go off-key. She wasn’t there when they made one of their notorious decisions—roundly mocked in the press—by selecting gothic thriller Red Ike as Book Society Choice in June 1931.

Behind the scenes, Sylvia sometimes overstepped. As the judges read manuscripts pre-publication, Sylvia often couldn’t resist intervening, ringing through suggested changes to authors and publishers.

Reading Vita Sackville West’s The Edwardians (1930), Sylvia felt the author should modify parts about King Edward VII to ensure a Book Society Choice (some of her other thoughts on character and setting were ignored). With Scottish writer George Blake’s novel, The Shipbuilders, language and dialect were tamed thanks to Sylvia’s views.

“Don’t know what upset Sylvia,” Eric Linklater asked his publisher after the Book Society’s deliberations on Juan in America (1931) left him with suggested revisions to make.

Upfront, Sylvia was a vocal champion for women’s writing. As a tastemaker on the Book Society, she celebrated the work of E. M. Delafield, Rosamond Lehmann, Ann Bridge, Margaret Irwin, and Kate O’Brien, while insisting that the club also recommend more challenging works by modernists like Virginia Woolf. Often her reviews draw attention to style and skill but the keynote is a commitment to entertainment.

“It is not with the critic’s cherished masterpieces that we sit up all night,” Sylvia wrote in a review of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (Book Society Choice, August 1938). What matters is the gift of storytelling, “of infecting the reader with a devouring curiosity to know what happens.”

Sylvia’s talent for spotting the best new writing by other women didn’t necessarily help her own work. There was always someone better to be aware of, writing something more worthwhile, making her doubt herself.

As a busy professional, juggling a career against competing demands of home and family (caring for her daughters and elder relatives, trying to support Robert’s long-running battles with alcoholism), prioritizing her own creative writing was hard.

But reviewing cemented her reputation as an influential critic. And as her own literary star began to fade during her lifetime, the parties and committees, with their connections and power deals, were where Sylvia continued to make her mark.

______________________________

Recommended! The Influencers Who Changed How We Read by Nicola Wilson is available via Holland House Books.

Nicola Wilson

Dr Nicola Wilson is the author of Recommended! The Influencers Who Changed How We Read (Holland House Books, 2025). She is Associate Professor of Book and Publishing Studies at the University of Reading and co-director of the Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing.