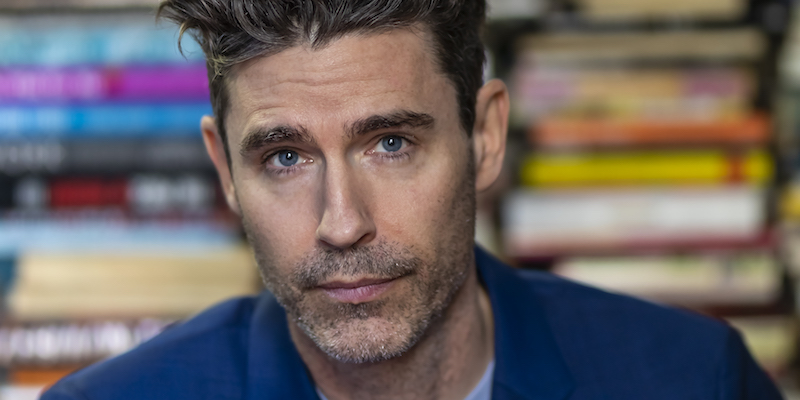

Joshua Ferris on Why the Family is the Perfect Site for a Novel to Develop

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

In this special episode, taped live at the Miami Book Fair, novelist Joshua Ferris joins hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new novel, A Calling for Charlie Barnes, which takes an often humorous look at the catastrophe of its protagonist’s life. When Charlie Barnes is simultaneously hit with a cancer diagnosis and the Great Recession, all he wants is to live within another story. Ferris talks about the lies we tell ourselves and the fictionalized accounts of the past that plague and define families.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video excerpts from our interviews at LitHub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website.

This podcast is produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

Excerpt from a conversation

with Joshua Ferris

V.V. Ganeshananthan: I’m interested in thinking about families as a space for fiction to develop. The idea of it as a place where people are telling different stories about the family to each other, lying to each other and for each other. And I also was interested in the notion of the way that you juxtapose ideas about workshop and about relationships.

Joshua Ferris: There’s a great movie called The Meyerowitz Stories by Noah Baumbach, and the Ben Stiller character is successful and strong, and he has sort of evolved beyond the familial conflicts. He’s telling someone this, and he gets sort of seduced back home. And the very minute that he gets there, he starts fighting with his father. And so these projections that we have of ourselves out in the world are instantly reduced back to the same three or four family narratives. The minute we step foot back in the family estate, and I find this fascinating, there’s no way to elude the straitjackets that we readily acquire as family members. You walk back into the family estate, and there you are.

Whitney Terrell: The eight-year-old that you were once.

JF: That’s what’s funny about families, that everybody is the underdog. Even the patriarch is the underdog. Everybody has these stories they tell one another, and they very infrequently line up, and they infrequently agree. So I’m fascinated by the fact that that’s where so much of our early selves come from, but also the fertile nature of the family to create these stories. And these stories that rarely can be reconciled one from the other teller. So I think that’s a perfect place for the novel to focus on because of these conflicting storylines.

WT: Another book that I thought of when I was reading the book was Geoffrey Wolff’s memoir, The Duke of Deception…It’s a favorite book of mine that I’m teaching this semester, and there’s a lot of deception in the novel. Charlie is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer earlier in the book, but he’s deceptive about his diagnosis. Jake, who’s telling the story, is deceptive about what happens to his dad in different ways. Jake says progress is a myth. I don’t know how to live without—that’s deception too—the idea of progress, as he says, but it seems in Jake’s mind to be a positive kind of deception. Can deception be positive?

JF: The distinction that I would make is this between illusion and delusion. And I would say that illusion is a healthy thing and a necessary thing. And this kind of goes back to some extent it goes much further back…But certainly in the 19th and 20th century, these were powerful forces in the philosophical world of psychology, the world of psychology, Freud, Nietzsche. But this is the distinction I would make: In the illusion, I might have the illusion that I’m going to be elected the president of United States one day, and it’s probably not going to happen. But you know, I’m of age, and I was born here, and maybe so. But I might also believe that I will be elected the first President of the United States, and that can only be George Washington.

And so I would be deluded. And I think that it’s very healthy to have the former and very unhealthy to have the latter. But I think it’s a distinction that really makes a difference, because the illusion that God exists might be a very powerful one in somebody’s life, determining a certain moral script and the arc of one’s life. It may not pan out, you may die, but it’s mighty powerful, and maybe even necessary to that individual. I think that progress for a long time was a myth I was under in the same kind of pervasive way. It seemed to color the world, it seemed to determine where we were when I was born, versus where my father was when he was born. I can now see it in my son who’s 12 and can’t imagine the world without the iPhone or the personal computer in a way that I have direct access to.

And so he sees that generational divide not merely as one of technological advantage or disadvantage, but of a massive break, in terms of where we were and where we’re going. So progress is very much alive for him. His sense of progress in the sense of living in an enlightened age. And I think that I did that. I did that in the same way that he’s doing it. And it was only really with the death of my father that I understood a number of the powerful illusions that I was under that kept me going. And it was only after I stopped grieving for him that I reacquired them and was able to go on. So I think illusion is a necessary and very frequently a very healthy thing to have. And, you know, they blend in to some extent, they might be called white lies, white lies to the self. They might even be called harder things. They might be called lies. But there is a distinction, certainly, between the kind of mendacity that we’ve seen on the national level over the past four or five years and the things that I’m talking about.

WT: Well, the idea of living a life where you’re only truthful is an impossible thing, right? And also, the business that we’re all in is about lying. And there’s something important about fiction, obviously.

*

Selected readings:

Joshua Ferris

To Rise Again at a Decent Hour

Others

Always on Display: An Interview with Joshua Ferris

Interview with Joshua Ferris, 2008 PEN/Hemingway Award Winner

The Duke of Deception: Memories of My Father by Geoffrey Wolff

James B. Stewart, The New Yorker

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary – 2021 M09 Results

“The Great American Bubble Machine” by Matt Taibbi

Meyerowitz Stories, written and directed by Noah Baumbach

__________________________________

Transcribed by https://otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Anne Kniggendorf. Photo of Joshua Ferris by Peter Aaron.