Jonathan Escoffery on How to Build Trust with Readers

"Readers come to the page wary that a story will drag on forever."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Years ago, before I had taken my first college-level creative writing course, I began working on a novel about a married couple who owned and operated a farm that was failing largely because they’d fallen afoul of their vindictive, politically connected neighbors. My protagonist, the husband, amped up by feelings of inadequacy and powerlessness, and by his moral rationalizations, winds up doing some very bad things in the name of defending the family farm. Also, for some reason, the farm is besieged by werewolves! Though they, of course, are the lesser antagonists.

As my word count grew, so too did my desire to share what I’d written. Seeking encouragement more so than critical feedback, I posted the opening chapter to an online writing forum, and though the feedback was largely positive—this was an unusually kind corner of the internet—one commenter pointed out a key flaw in my chapter: nothing happens in it. Being thin-skinned, I might have found offense with any number of accurate statements he might have leveled against my submission, but because the chapter opened with an attack on the farm—again, werewolves—and an action sequence—a chase, a shooting, a killing—the comment also left me scratching my head. I shrugged it off as best I could and wrote another eighty more pages before abandoning the project.

Later, I came to take away from that first bit of criticism that I had yet to imbue the happenings on the page with meaning. In a sense, too much happened too quickly. The what happened before the why should anyone care? Although my characters’ lives were at stake, I hadn’t worked in who they were, or the larger context for what it all meant. But what strikes me as an equally important observation is that I wasn’t yet having a coherent conversation with the reader, and that I hadn’t built in enough gestures to suggest that they should trust that I was taking them anywhere worth going.

In early workshops, we often talk about character desire and how it’s intertwined with, if not the direct source of, the story’s conflict. There’s rising action that moves towards a climax before the conflict is resolved. Many of us will have seen this sketched out on a whiteboard or elsewhere, and it might resemble an inverted checkmark or an unfinished mountain peak. For me, I think it’s useful to think of story in terms of managing reader anticipation. This anticipation might be built in with implied questions, or questions that your narrator or characters explicitly ask, that readers will want to see answered through dramatization. But even with a gripping set of opening questions, readers come to the page wary that a story will drag on forever, and you can mitigate this by telling them exactly how long the story will take and even where there’ll spend that time.

In the penultimate story in my collection, the protagonist, Delano, attempts to resurrect his defunct tree service before a hurricane makes landfall in Miami. Whether or not that’s an intriguing enough premise to get us reading, we should understand the question at hand: will he or won’t he succeed? The threat the hurricane poses to the area creates the conditions for his mad dash attempt—property managers across the city will need to ensure the trees in their communities are trimmed and in good enough condition to weather the storm, otherwise they’ll leave themselves open to lawsuits. Through a verbal disagreement with his business partner, Delano explains the three things they’ll need to succeed: they’ll need to convince a particular property manager to greenlight their working on her property, they’ll need to find a crew to do the grunt work, and they’ll need to retrieve the bucket truck they left at an especially disgruntled mechanic’s shop. Their challenge is that they have no money to pay the mechanic or the crew, and the property manager and Delano left their previous negotiations on very bad terms.

Making sense of the present action and establishing character motivations can be as much about panning forward as it is about establishing our characters’ histories.

So we know what Delano wants, what sets him in motion on today of all days, we know his time constraints, and we know where he intends to go and who he intends to interact with. I forefront some of Delano’s upcoming troubles by changing the title from “The Bucket” to “If He Suspected He’d Get Someone Killed This Morning, Delano Would Never Leave His Couch.” I begin the story, “But Delano is not clairvoyant.” Now I’ve made a specific promise to the reader, and hopefully they’ll want to see how it plays out.

Of course, it’s still my job, as the writer, to establish the stakes as best as I can. In this case, Delano’s wife has moved their kids out of state and he needs to get his business back on track, if he’s to compel her to bring them back. Some of this information is established in back story. It may be useful to think of the trials Delano embarks on through the inverted checkmark, but I’ve begun thinking of this kind of story construction through the image of a Slinky toy walking its way down a set of steps. At one end of the Slinky, I have all the information that explains what led Delano to this current moment of crisis and at the other end I have all his hopes for how things will go. The two ends meet during the present action, that which is actually happening. When we’re certain we have our readers rapt attention, we have room to explore what led to our characters present conditions, and by the time they’re back in present action readers should be that much more invested in the present journey. The part we writers sometimes forget is that we can tell readers how our heroes hope or expect things will go, so that when things don’t go that way (and they shouldn’t)—when we subvert both readers and our characters’ expectations—readers feel our characters’ pain and understand where they are on the storyboard. Making sense of the present action and establishing character motivations can be as much about panning forward as it is about establishing our characters’ histories.

If I ever return to my werewolf farmer thriller, I might build in my hero’s hopes and dreams and expectations, so that readers can feel invested when it all goes to hell.

__________________________________

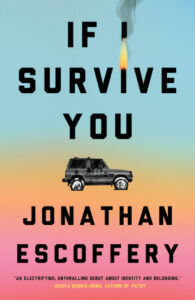

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery is available via MCD.

Jonathan Escoffery

Jonathan Escoffery is the recipient of the 2020 Plimpton Prize for Fiction, a 2020 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, and the 2020 ASME Award for Fiction. His fiction has appeared in The Paris Review, American Short Fiction, Prairie Schooner, AGNI, Passages North, Zyzzyva, and Electric Literature, and has been anthologized in The Best American Magazine Writing. He received his MFA from the University of Minnesota, is a PhD fellow in the University of Southern California’s PhD in Creative Writing and Literature Program, and in 2021 was awarded a Wallace Stegner Fellowship in the Creative Writing Program at Stanford University. If I Survive You is his debut book.