Streaming Autofiction: On Nathan Fielder’s Search for Authenticity in The Rehearsal

Yurina Yoshikawa Places the HBO Series in Context with Its Literary Predecessors

When I first started watching Nathan Fielder’s HBO series The Rehearsal, the first comparisons that came up in my bookish mind were novels like Tom McCarthy’s Remainder or Ashley Hutson’s One’s Company, which imagine protagonists who, after receiving millions of dollars, decide to spend all their money creating replicas of real-life situations or sets from TV shows they loved—simply because they can.

As I continued watching (and re-watching certain scenes) from The Rehearsal, I realized that the show was closer, as an artistic organism, to works of autofiction. The word is a combination of “autobiographical” and “fiction,” and one could argue that almost all works of fiction are in fact autofiction in that sense.

But in light of the international bestselling success of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series (2009 onwards), I’ve noticed more and more books that intentionally straddle and play with the boundary between fiction and nonfiction. Having been fascinated with these books as a reader, I ended up teaching a six-week class last fall on this genre-bending genre that readers either seem to love or hate.

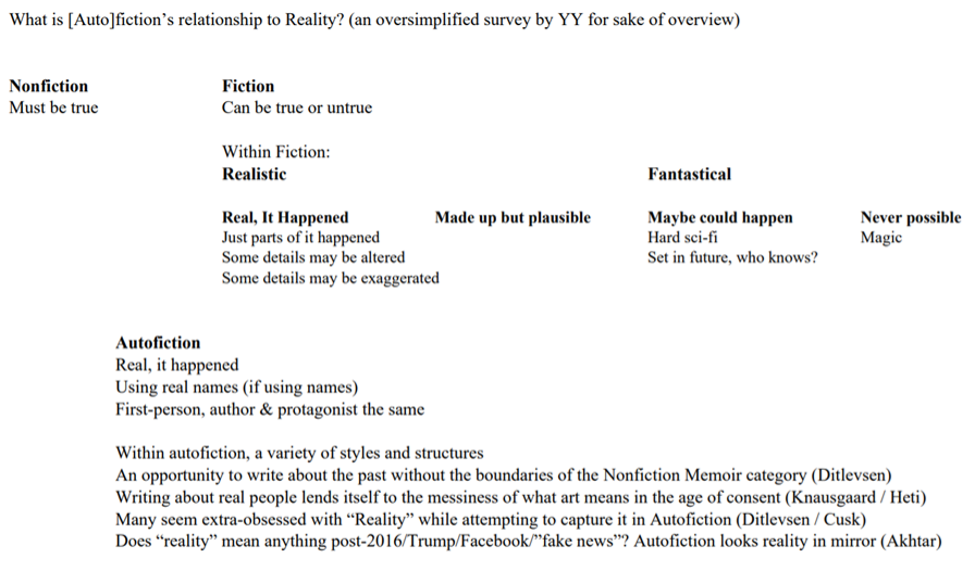

Below is the diagram I made for my students to describe the basic differences between fiction, nonfiction, and autofiction. I admit, the diagram is oversimplified for the sake of the class, and it is by no means comprehensive or complete, but I still find it useful as a starting point for discussions like the one I’m about to get into.

Judging by this diagram, if The Rehearsal were made as a work of more traditional fiction, it may have looked more similar to Charlie Kaufman’s 2008 film Synecdoche, New York, also about a man who spends an exorbitant amount of time and money to recreate scenes from his life, with actors playing himself and understudies following the actors, and so on and so forth. In the “never possible” end of the fiction spectrum, one might even think of Marvel’s WandaVision and how the protagonist inadvertently, then knowingly, forces strangers to act as actors and extras in her fantasy TV-inspired town.

If The Rehearsal stuck closer to the reality TV or documentary format, it may have given room for sidebars and voice-overs from participants and crew members instead of just showing us the narrative from Fielder’s perspective. It would have been more like the 2017 documentary film Casting JonBenet, where the filmmakers used rehearsals and interviews with the actors to tell a separate story about the lingering hold that the JonBenet Ramsey murder still has on people (particularly residents of Boulder) today.

What makes The Rehearsal closest to autofiction has to do with Fielder’s self-conscious endeavor to create something so authentic that the result is surreal and shocking like a work of fiction, and yet, at the end of the day, real people are involved. The result, for me, was as uncomfortable as it was endlessly fascinating.

In the first episode, Fielder helps a man named Kor rehearse an uncomfortable confession, which will take place at a real bar called the Alligator Lounge in Williamsburg. Fielder, powered by his HBO budget, creates an exact replica of the Alligator Lounge inside a warehouse, where Kor and an actor portraying his friend will rehearse this conversation until he’s fully prepared—in theory.

It’s unclear, aside from the entertainment factor, whether every detail in Fielder’s expensive replica was necessary for the sake of these rehearsals.It’s unclear, aside from the entertainment factor, whether every detail in Fielder’s expensive replica was necessary for the sake of these rehearsals. Would Kor’s peripheral vision containing a partly deflated balloon on the ceiling actually help prepare him for his real conversation?

This question—was that necessary?—reminds me of my experience reading Knausgaard’s My Struggle books, which total over 3,700 pages over six volumes. The books might contain epic epiphanies and beautiful observations, but the pages are also jam-packed with details that provide a high-def version of his childhood memories that may or may not be pertinent to anything. “I straightened up, picked some splinters of wood off my shirt, and sat in the chair while Dad crouched down, opened the stove door and pushed in a couple of logs. He was wearing a dark suit and a dark-red tie, black shoes, and a white shirt, which contrasted with his ice-blue eyes, black beard, and lightly tanned complexion.” As a reader I might quickly forget the colors of the dad’s outfit, but the writer deemed these details important enough to keep.

Even Fielder himself might consider Knausgaard’s attention to detail “a work of art,” like when he steps inside the real home of one of the show’s child actors and notices the clutter in the closet (a panda costume and a pool noodle in a sea of clothes) or a stray battery sitting on the kitchen counter. “I wasn’t used to this level of detail,” Fielder says, marveling at the real house like it’s a film set. “Every object was perfectly placed but nothing was by design.”

In a different scene, Fielder says in another voice-over, “The nice thing is, sometimes all it takes is a change in perspective to make the world feel brand new.” Fielder, as the show’s director, producer, writer, and actor, has full control over his participants’ rehearsals, though he might claim that the rehearsals are for them. When a parenthood simulation goes awry, Fielder can rewind the rehearsal to when the child is much younger, to let the participants start over and get it right this time. He can even simulate the same scenarios but from different perspectives. Fielder gets an actor to play Nathan Fielder, and Fielder, as an actor, steps into the role of one of the child actor’s mothers.

Representing real people for the sake of art, or a TV series that’s meant to be “funny, but interesting,” is inevitably going to get messy.When a writer writes fiction, one of the biggest challenges is getting into different characters’ heads. For example, when a white writer attempts to write a character of color and does it without sufficient research, understanding, or empathy, they can be called out for appropriation and racism. In nonfiction, a writer might try telling other people’s stories by way of direct transcripts and research, but it would be unethical for a nonfiction writer to assume the unspoken elements of another person’s story and print them as though they were accurate.

In autofiction, because the line between fiction and nonfiction is already so blurred, writers are able to do something similar to what Fielder does when he plays with perspective. Knausgaard, in describing a memory of his father when the writer was eight and his father was 32, goes back and forth between his eight-year-old POV and 39-year-old one: “My picture of my father on that evening in 1976 is, in other words, twofold: on the one hand I see him as I saw him at that time, through the eyes of an eight-year-old: unpredictable and frightening; on the other hand, I see him as a peer through whose life time is blowing and unremittingly sweeping large clunks of meaning along with it.”

In one of the most memorable moments of the season, Fielder does his own rehearsal for an uncomfortable conversation he has to have with one of the participants named Angela. Fielder thinks she’s not taking the rehearsals seriously, and he wants to know what she hopes to get out of this experience. An actress, who is labeled Fake Angela in the subtitles and credits, stands in to help prepare Fielder.

Fake Angela: So, is this silly? Or is it something that I should take seriously?

Fielder: It’s silly and serious. I mean, it’s complicated. Life can be more than one thing, right? Life’s complicated, and… Why are you even here, huh? What’s the real reason? Honestly?

Fake Angela: Okay, well, why are you here? Huh? Why are you doing this? Are you really trying to help me? Or am I the silly part that you talk about, huh? Is my life the joke? Do you sit here with your friends at the end of the day laughing at me?

Fielder: No, you’re not the joke. Not at all. No one’s the joke. The situations are funny, but interesting too.

Representing real people for the sake of art, or a TV series that’s meant to be “funny, but interesting,” is inevitably going to get messy. In Sheila Heti’s 2012 novel How Should a Person Be?, the autofictional protagonist, Sheila, is experiencing writer’s block and enlists her painter friend Margaux for help. She records and transcribes one of their conversations that leaves readers with the same discomfort as the Rehearsal scene with Fake Angela.

Margaux: Why are you looking to me for answers? I don’t know anything you don’t know!

Sheila: I’m not looking to you for answers! Why would you say that? I was just hoping that if I—

Margaux: Don’t you know that what I fear most is my words floating separate from my body? You there with that tape recorder is the scariest thing!

In Ayad Akhtar’s 2020 novel Homeland Elegies, there’s again a similar moment when Akhtar’s father asks him if he’ll be included in the book. Akhtar says no (and includes this dialogue in the book itself), but his father continues to worry that he’ll be portrayed “like an asshole.” Akhtar assures him it won’t be him, just “someone like him.”

In an interview, Akhtar says he was drawn to the autofiction form as a way to break through to contemporary readers who are collectively drowning in content:

“I wanted to reclaim that vivid present, and I wanted to find a way to do so to a reader today without asking them to change, without asking them to stop being addicted to the breaking news notification or the absorption in the Instagram scroll. Thereby, if I could breach that sanctum sanctorum of contemporary attention, that we could then together have a meaningful, productive, and perhaps even deep conversation about our politics. I was using the form, if you will, not to critique it in part, to mirror it for sure, but ultimately to find a way to reach the reader more deeply.”

Homeland Elegies begins with the anniversary of Trump’s first year in office and tells many stories, including those of Akhtar’s parents, who immigrated to the US from Pakistan; Akhtar’s own experience as a successful playwright in New York; and even his dream journals in order to paint an authentic, comprehensive portrait of living in post-9/11 (and later Trump’s) America. The book, with its innovative storytelling techniques and shocking moments, forces readers into these “deep conversations about our politics” that Akhtar sought to have when deciding on the autofiction form.

Ayad Akhtar says he was drawn to the autofiction form as a way to break through to contemporary readers who are collectively drowning in content.

In that way, The Rehearsal also succeeds in getting people to talk about things that the audience would have never expected after reading the premise or watching the trailer. Once you’re hooked on the surrealness of the exact replica of the Alligator Lounge, the show sets the spotlight on things like the real participants’ casual and pervasive antisemitism. We witness Fielder’s conundrum as a Jewish person who’s immediately offended, but as a perfectionist showrunner of the participants’ rehearsals, he’s pulled into complacence for the sake of maintaining the rehearsal’s authenticity. His show also sheds light on the ethics of Hollywood’s use of child actors, which I’ll continue to think about in any show or movie that uses actors, especially under the age of eight.

I didn’t realize, until spending time with autofiction or The Rehearsal, how much I have been yearning to ask big philosophical questions and deep dive into conversations we otherwise might not have. Questions like: How can fiction be useful for our real life? How do we deal with the consequences of representing real people in a project that other people will see? What is reality, anyway?

As a writing teacher, I asked these questions to the students in my autofiction class, and the discussions were fruitful while simultaneously feeling, well, rehearsed. It occurred to me that autofiction books like the ones I assigned attract a relatively small niche of literary readers and writers who have already wrestled with these questions on some level.

Watching The Rehearsal, which was like watching literary autofiction come alive on the screen, reassured me that there is a larger group of people who are interested in these big questions. After all, the show was successful enough to secure itself a second season despite many other shows being cancelled or removed from HBO Max in the same week. While we wait for more of this TV autofiction, my hope is that some of those fans will gravitate toward these literary predecessors, even if it’s more time-consuming to read a 3,000-page equivalent of the Alligator Lounge replica.

If studying this literary genre taught me anything, it’s that we’re still in the thick of this artistic movement, and we’ll likely continue to see different attempts by more artists in the coming years. I not only yearn to ask these big questions again, I also want to be shocked and challenged by these future attempts.