Literary biopics have often played fast and loose with the facts. Perhaps the most ludicrous example in cinema history is Warner Brothers’ 1946 Devotion. Starring Olivia de Havilland as Charlotte, it tells the story of the Brontës, though not as we know it. Their actual lives were deemed insufficiently exciting by the studio, so a completely spurious love triangle was interpolated, with Charlotte and Emily in love with the same man. Arthur Bell Nicholls—the reticent clergyman whom Charlotte in real life later married after her sisters died—becomes the unlikely object of their competing affections.

Jane Campion’s exquisitely crafted Bright Star (2009) is based on the last two and a half years of poet John Keats’ life (played by Ben Whishaw) and his romantic relationship with Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish). The film is a showcase for Campion’s painterly imagination, seen most recently to such astonishing effect in The Power of the Dog. But how accurate is it in its portrayal of the poet John Keats and the love of his life, Fanny Brawne?

Fans of Bright Star will be relieved to hear that it contains no such unfortunate solecism. Keats really was smitten with Fanny, and she returned his love. Moreover, the movie sticks more faithfully than you might have feared to the chronology and real-life events, helped by the fact that Campion employed Keats biographer and former British Poet Laureate Sir Andrew Motion as a consultant on the project.

The action takes place between sometime in the autumn of 1818 and September 1820 when Keats, desperately ill with tuberculosis, left London for Rome. The supposed health benefits of the warmer Mediterranean climate proved a mirage. He died there on February 23, 1821, at the tragically young age of only 25.

This was a love that flourished in a private bubble created by the lovers.The film opens with the 18-year-old Fanny, along with her mother and younger siblings, visiting the mutual friends through whom they first met Keats: the Dilke family, who live in a house divided in two. The other half is inhabited by Charles Brown, another of Keats’s friends. As is accurately portrayed in the film, Keats will later move in with Brown and then the Dilkes will move out, giving over their half of the house to the Brawnes—with the result that by the late spring of 1819 (the period in which the poet wrote all his great odes except ‘To Autumn’) he and Fanny are next door neighbors, allowing their intimacy to develop.

Keats purists might bridle at the appearance of the house in the film. A redbrick, Queen Anne mansion, fronted by an elegant stone balustrade, it is far bigger and grander than the actual one in London’s Hampstead, where all this actually happened. Now the Keats House Museum, but then called ‘Wentworth Place,” the reality was a pretty but modest Regency villa, stuccoed and painted. Far from being a heritage property, in 1818 it was a suburban newbuild (though the subsequent boom in London property prices means that today the other real estate in the street is only affordable by high net worth bankers).

Key episodes in the film are based on real events. Keats, for example, really did spend Christmas day 1818 with the Brawnes—and Fanny later described it as the happiest day she had then yet spent. Keats entertains his hosts by dancing a Scottish caper. He really had seen a display of such dancing on a trip to Scotland the previous summer, and had vividly described it in a letter home.

Fanny’s side of the correspondence is lost, but her viewpoint, sympathetically re-imagined by Jane Campion, is the film’s most intriguing innovation.The motherly Mrs. Brawne must have invited Keats, an orphan, for Christmas out of concern for the fact that he had recently been bereaved. His younger brother Tom, with whom he had been living, had died on December 1 of the tuberculosis that would later kill his more famous brother. In the film, Keats and Fanny are already on a footing of some domestic intimacy before Tom’s death: she bakes biscuits for the invalid.

But Keats’s first documented mention of her does not come until December 16, in a letter to his other brother George, who had emigrated to America. He introduces Fanny as a relatively recent acquaintance, “beautiful and elegant, graceful, silly, fashionable and strange we have a little tiff now and then—and she behaves a little better.”

This sounds as though there is already some flirtation in play, but it might come as a surprise to viewers of Bright Star that Fanny was not the first woman Keats had desired. In 1817 he confessed to a friend that he was treating himself with mercury for syphilis, “the Poison” as he calls it. We don’t know how he caught it, but his letters contain many allusions to sexual experimentation with barmaids among his male friendship group—plus a bawdy early poem in which Keats describes himself, probably in fantasy, as having sex in a field with a girl called Rantipole Betty (in the vulgar slang of the time, to “ride Rantipole” meant with the woman on top; the humor of the verses stems from the fact that Betty is flat on her back, “dead as a Venus tipsy”).

More interesting than any possible casual encounter—and there only needed to be one for him to catch “the Poison”—is the fact that we know for sure that Keats made a pass at another woman around the time he was first getting to know Fanny: the alluring and enigmatic Isabella Jones, who called herself Mrs yet lived a single life. He had first met her at the seaside the previous year, when he had, in his own phrase, “warmed with her and kissed her.” In October 1818, he tried to kiss her again in her apartment in London, but she teasingly rebuffed his advances on that occasion, though she sent him away with a red-blooded gift: some game for dinner.

According to Keats’s publisher John Taylor, Isabella also went on to give him the idea for one of his most erotic poems, The Eve of St Agnes, written in January 1819, which Taylor feared was too explicit and went “against all decency and discretion.” A letter of February 19, 1819 reveals that eight weeks after that cozy Christmas dinner with the Brawnes, Keats was still in touch with Isabella Jones, who was still giving him tasty gifts of meat.

But we also know that by the summer Fanny had completely displaced any other possible other woman for Keats. “I never knew before, what such a love as you have made me feel, was; I did not believe in it; my Fancy was afraid of it, lest it should burn me up,” he told her on July 8 in the second of 39 surviving love letters addressed to her, written while he was away from Hampstead. Prior to that, we can’t trace exactly in real life how the relationship moved from non-committal flirtation to grand passion, as Keats does not open up to his brother or other correspondents in the period in which it first burgeoned. This was a love that flourished in a private bubble created by the lovers. It is only because Keats then went away and had to communicate with Fanny by post that we have any access at all to his feelings.

He wants to be so close to her that she has no separate identity. At the same time, he also pushes her away.Fanny’s side of the correspondence is lost, but her viewpoint, sympathetically re-imagined by Jane Campion, is film’s most intriguing innovation. It does her a justice that posterity denied her. Her name was not even mentioned in the first biography of Keats, Richard Monckton Milnes’s 1848 Life and Literary Remains. Long after Keats’s death, members of his circle disparaged her as “a cold, conventional mistress” and as a shallow flirt who “made all the advances to him without caring much for him.” Charles Brown in the film—who is dismissive of Fanny and tries to put Keats off her—stands in for their collective ambivalence towards the relationship.

That was unfair. Fanny’s letters to Keats’s younger sister (whom she got to know after he died and who does not appear in the film) reveal her to have been intelligent, articulate—and far from cold. She loved Keats and his death devastated her, although she was also emotionally resilient (“I have no pity for your nerves, as I have no nerves,” she teased her correspondent). It is from these letters, which include a couple of delightful sketches for dress designs, that Campion’s portrayal of Fanny Brawne’s interest in fashion derives.

Fanny’s sanity and resilience must have been a ballast to the agonized intensity of Keats’s need for her—and his panic at it. He wants to be so close to her that she has no separate identity. At the same time, he also pushes her away. There’s a level of emotional brutality when he channels Hamlet’s cruelty to Ophelia, telling Fanny “Go to a nunnery, go, go!” Having been abandoned by his mother in childhood after his father died, Keats was afraid that he had, as he confessed to a friend, “not a right feeling towards Women.” Very few young men in their early twenties—even now let alone in the Regency—would be that self-searching and honest about the complicated desires and fears the opposite sex aroused in them.

In the movie, Keats glancingly admits that “women confuse me”, but Ben Whishaw’s charmingly understated and sweet-natured performance softens some of the poet’s edges and in a sense “normalizes” him. The real Keats was sweet-natured and extraordinarily empathetic, but he was complex too. Aspects of him that don’t make it onto the screen include the forceful drive that powered his poetic ambition (he was famous for fisticuffs at school); his daring political radicalism, at a time of government repression, which led to excoriating personalized attacks by the right-wing press; his previous abortive career as a trainee doctor; his mood swings and self-confessed paranoia; and the sheer mystery of how his extraordinary and original literary gifts came out of nowhere to revolutionize English poetry. The film gives us relatable romance but cannot—and could never have attempted to—give us a nuanced historical thesis on Romanticism.

One problem all literary biopics face is how to represent the writing life.Biographically, Campion if anything underplays Keats’s physical and emotional suffering, in an unusual case of the movie version being less melodramatic than the reality. When, in February 1820, Keats has the pulmonary hemorrhage which he knows to be his “death warrant”, all we see on screen is a spot of blood on a cloth in the kitchen. No viewer, of course, would want to see a realistic portrayal of someone coughing up their lungs, but the result is slightly sanitizing. The use of Fanny’s viewpoint here works well; to be inside Keats’s subjective experience would simply be too painful.

It is a relief that the film does not show Keats’s last days in Rome, described in real-time in letters by his friend Joseph Severn, who went with him: not just the coughing, but the diarrhea, the uncontrollable shaking, the blood, and other bodily fluids, the suicidal thoughts. Keats kept clutching for the laudanum bottle in the hope of dosing himself to death. In his delirium he believed that sexual frustration—“the exciting and thwarting of his passions”—was responsible for his sickness: that he would have been healed had he gone all the way and slept with Fanny: “I should have had her when I was in health, I and should have remained well.”

The delicacy with which Bright Star portrays the couple’s hesitant love-making can only be commended from a cinematic viewpoint. As with the blood-spitting, we wouldn’t want to see too many torrid fumblings, as it would immediately seem lurid, gratuitous, and embarrassing. At the same time, Keats’s letters and poetry show him to have been a very physical being. One of his early poems is about the “lewd desiring” inspired in him by a woman with beautiful breasts he once caught a glimpse of, and his bodily appetites are indicated by his paeans to claret and roast-beef sandwiches, and even by his entranced depiction of eating a nectarine: “good god how fine—It went down soft pulpy, slushy, oozy—all its delicious embonpoint melted down my throat.”

Bright Star quotes in passing the Keatsian phrase “slippery blisses”, used in Endymion to depict a woman’s lips; but it does not register how contemporary critics recoiled from such phrases as “gross” (there’s an implied body fluid here, saliva). Modern viewers of the film might not quite register the full erotic implications when Keats tells Fanny—it’s a direct quote—“But if you will fully love me, though there may be some fire, twill not be more than we can bear when moistened and bedewed with Pleasures.” In the Regency era, there was no other way to talk about sex except in metaphors and euphemisms. Moist desire is not something you’d imagine appearing in a courtship letter in a Jane Austen novel.

The film is quite right to indicate that Keats could not formally propose to Fanny because he had no means to support a wife and family through his literary earnings. But this was not just an external prohibition. Had marriage been his overwhelming aim in the summer of 1819, before his health collapsed, Keats could have gone back to the stable and secure medical profession for which he had trained before turning to poetry full time. The truth is—and we are talking about the era of Byron and Shelley—that he identified with the rebellious bohemian avant-garde rather than with the conservative Austenian institution of marriage. “Better be imprudent moveables than prudent fixtures,” he told Fanny; “god forbid we should what people call, settle—turn into a pond, a stagnant Lethe—a vile crescent, row or buildings.”

After Keats died, Shelley wrote an elegy that transformed him into an ethereal, spiritualized essence and frail flower. But the real Keats was attuned to the paradox of what he calls, in his sonnet on King Lear, “impassioned clay.” His genius was to apprehend the co-existence in the human condition between materiality and spirituality, between the physical body and the instinct to yearn after an ideal. None of his poems offers an unmixed vision: Ode to a Nightingale has circling “flies”; To Autumn has “wailing gnats.” His ideas of Beauty and Truth in fact incorporated, without denial, ugliness, and contradiction. It is the tensions in his poetry that give it its creative energy, and Keats’s love for Fanny was equally riven with conflicting impulses.

One problem all literary biopics face is how to represent the writing life. Famous poets are people whose most intense and significant experiences are perhaps those that happen when they are sitting still and alone in front of a soon-to-be filled blank page—not a recipe for dramatic interest. Bright Star ends with Ben Whishaw reciting Ode to a Nightingale over a musical soundtrack, but the medium of film can’t, in the end, replicate the fecund nuances of Keats’s poetry: what his friend and first public promotor, the radical journalist Leigh Hunt (who first got Keats into print but who does not appear in the film) called his “poetical concentrations.”

Keats was an extraordinary innovator of what you can do with metaphor, as is evident in the Nightingale ode’s second stanza, where wine, a “draught of vintage”, can taste of: a classical goddess (“Flora”); green fields in the countryside; dancing; songs from medieval Provence, where the poetic troubadour tradition was started; indeed, the whole Mediterranean “warm South”—including the Hippocrene fountain, a spring in Helicon sacred to the ancient Greek muses. It’s a glass of wine whose “beaded bubbles” (that’s already two ideas in one) can “wink” like an eye.

And the result of drinking might be a “purple-stained mouth”—an image that harks back to the Nightingale of the title in an allusion to the myth of Philomel, whose tongue was bloodily torn out by her rapist Tereus, but who was then turned into a nightingale by the gods. Her fate was to forever sing a beautiful lament whose meaning would never be understood by human listeners. And that’s only to scratch the surface of one stanza of Ode to a Nightingale, whose human readers are required to strain to the utmost to register all its implications. To understand the full import of Keats’s words is a challenge offered defiantly up by him. You could—as critics have indeed done—go on for page after page and still would not have fully described the stanza.

It is very unlikely that Keats in reality gave Fanny formal poetry tutorials as portrayed in the film, though we know he marked up passages in, say, Spenser, for her. In her letters to Keats’s sister after his death, Fanny describes herself as “by no means a great poetry reader.” But she was spot on when she said she felt it was impossible to write about literature in a letter: “for before you can get out your sensations about one line the letter is finished.”

You only have to look at one line of Keats to see how right she was. To describe what’s going on can take a seasoned academic critic several pages of a monograph. Bright Star is right to champion Fanny as more than a shallow flirt and its visual beauty is to die for. But even Jane Campion’s uniquely exquisite filmic imagination can’t in the end register the full literary, historico-cultural or psychological complexity of Keats.

_________________________________

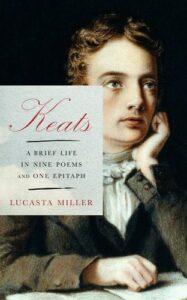

Excerpted from Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph by Lucasta Miller. Copyright (c) 2022. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.