Along a seaside promenade there are notices announcing that dogs are strictly forbidden on the beach. It is early October. There are no swimmers. People, however, are strolling along the sand and a few are sunbathing. More than half of them are accompanied by dogs. We are in Italy.

The beach is on the outskirts of the fishing town of Comacchio in the delta of the river Po. Venice is 84 kilometers to the north, Ravenna 30 kilometers to the south.

There is water in whichever direction you look. Salt water from the sea, fresh water from the arms of the great river. Half-island, half-lagoon, it’s a place that seems to belong to no continent. Everyone here—men, women, and children—can handle a boat.

In the town there are as many canals as streets. The economy of the place depends upon fishing and, above all, on eels—on catching, preparing, smoking, and exporting eels as a gastronomic fish delicacy.

All of the town’s trades are connected with water, and the isolation that this implies perhaps explains the physique of its inhabitants. The women and men of Comacchio are recognizably different from their neighbors. Stocky, broad-shouldered, weather-tanned, big-handed, used to bending down, used to pulling on ropes and bailing out, accustomed to waiting, patient. Instead of calling them down-to-earth, we could invent the term down-to-water.

Every year in the first week of October they celebrate a fête known as the Sagra dell’Anguilla (the festival of the eel). The cobbled town centre is crammed with stalls of street-vendors, come from elsewhere, selling trinkets, rings, seashells, cheeses, madonnas, salamis, dolls at low prices, small pleasures. The inhabitants wander slowly past, fingering the knick-knacks, reckoning the small pleasures and from time to time paying out a few coins. There are also benches and trestle tables where one can drink and eat. There is the smell of food being grilled. Onions, aubergines, peppers, and, of course, eels.

The eels when they are caught are a mercury silver, about 40 centimeters long and usually more than 10 years old. When they are younger and smaller they are yellow. Before that, when they are newly hatched, they are transparent leptocephali, smaller than tadpoles. They hatch out deep in the Sargasso Sea, opposite Mexico. It takes them three or four years to cross the Atlantic, following the Gulf Stream, and to arrive at the mouth of the Po.

There they exchange salt water for fresh water, settle in the wetlands of Comacchio, and grow large. After a number of years the urge comes over them in the autumn to return to the ocean bed they originally came from and to spawn. Having spawned, they die there amongst the Sargasso seaweed; the new, tiny transparent leptocephali then recross the ocean alone.

It is when the fully grown eels are leaving the wetlands of Comacchio each autumn that most of them are caught. As they set out to rejoin the salt sea, they unknowingly swim into the traps cunningly arranged by the fishermen. These traps they call the lavoriero.

Today, apart from those working and selling at the fair, nobody is working. The boats are moored and still.

In the Piazza XX Settembre of Comacchio, beside the medieval bell tower, a folk group is setting up. There’s a battery, a violinist, a double bass, a flutist, and a male singer. Three men and two women with their cables, mics, instruments, lights, music stands, debris. All of them are wearing either trousers or skirts of the same tartan. Their legs and arms are bare. It’s hot.

Michele, the male singer, mouths a syllable to the other players, takes the guitar, and strikes a note. Lilia picks it up on her flute. The sound is so full of promise you catch on straightaway why Plato, the idealist, banished the instrument from his city-state. Michele’s voice lets out the words syllable by syllable and between them his body swings.

Some passersby stop to listen. Then others pause and stop. An eight-year-old girl and a boy of four begin to dance on the cobbles between players and public. They are probably the kids of one of the musicians.

The listeners form a half-circle and, encouraged by Michele, start clapping to the beat and swaying to the rhythm.

What Laia is doing with her violin, as she turns in circles, head bent forward as if she were giving suck to a baby who is drawing out not milk but notes, what Laia is doing with her fiddle, a hundred people are now following with their humming and stomping.

They don’t have musical instruments but what they are playing on and improvising with are their own sensations and convictions about being alive at the moment when this day is ending and the evening beginning.

How do the leptocephali find their way over the ocean bed to the river’s mouth? If they are remembering something, it is something that occurred before they existed. What do they follow? The question has to answer itself. Or, are certain questions answers?

How does the music being played and improvised in the Piazza XX Settembre find its way with equal assurance into the hearts of a hundred or more unique and diverse lives? What is it listening to beneath itself?

Cesária Évora died in 2012 at the age 70. It was not until she was in her fifties that she became a legendary world-loved diva. She sang black West African Portuguese songs in a language and with an accent that was incomprehensible to most people who were not from Cape Verde. She was intransigent, obstinate, recidivist. The pitch of her voice was that of a teenager trying her luck in a bar for sailors before going home to look after her sick mother. “Every dog has his Friday,” she once said.

When she tours the world—the present tense is obligatory—she fills gigantic stadiums, yet she isn’t exotic; she is poor. She has a round face like a bosom. When she smiles, which she often does, it is a smile that comes after the tragic has been assimilated. The rich listen to songs; the poor cling to them and make them their own. Life, Évora said, consists of gall and honey. She sings our incomprehensible lives to us.

In the Piazza XX Settembre, the song ends and the silence is different. It is now a waiting silence. The musicians consult and get their breath back. The throng from Comacchio stands there relaxed, leaning against the silence as if it were a wall. From among the passersby a few newcomers join them. Some shake hands or touch a shoulder.

Then they all wait as they do for the tidal water to rise before climbing into and pushing off in one of their flat-bottomed boats.

Whilst they are waiting, I want to go 30 kilometers south to the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, outside Ravenna, and there I want to show you a basin mosaic in the sixth-century apse. It has the form of a scallop shell, a good ten meters in diameter, enclosing about the same space as the folk group occupy in the Piazza XX Settembre.

The basin mosaic shows the earth and sky, with trees, birds, grass, stones, sheep. At the top is the open hand of God no larger than a pebble. In the centre is the head of Christ, no larger than the palm of God’s small hand. The principal colors are greens, white, gold, and a turquoise blue. Its nominal subject is the Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor in Galilee (see chapter 9, St. Mark’s Gospel). But what it does as a mosaic is to transfigure space! Perspective and vanishing points are abolished. Each entity we see—be it a flower, a sheep, a tuft of grass, a pebble—is at the center of the whole; nothing in the scene is marginal.

The arching mosaic evokes in terms of space something like what eternity may evoke in terms of time. It simultaneously contains and abolishes space. Distance here brings together instead of separating.

How does it achieve such a transfiguration? The secret is in the way the mosaic’s tesserae play with the light. These tiny cubic pieces of glass, marble, and mineral generate, because of how they are placed together, an extraordinary visual energy. How do they do this?

The tesserae vary in their different tints of the same colors. No two are quite the same. The angle at which they were inserted into the mortar (14 centuries ago) also varies, sector by sector, and this means that the light they reflect is in places bright and in other places opaque—as happens in nature when light is reflected off moving water. And, finally, the lines of the tesserae—the convoys in which they proceed across the curved mosaic—are never straight but always more or less serpentine. They proceed like eels.

When you look up and watch the whole mosaic, everything you see is motionless and calm and at the same time part of a ceaseless orbital spin!

This is why each entity—each tree or flower or sheep or stone or prophet—wherever it has been placed and whatever its size—becomes, when you watch it, the center of everything surrounding it.

The song they choose next in the Piazza XX Settembre is “Il Pescatore.” It was written and first sung in the 1970s by Fabrizio De André. For two generations kids all over Italy hummed and sang it.

The song tells the story of an old fisherman asleep on a beach. His face is creased, furrowed in a smile. Another guy—a man on the run—appears. On the run. He begs for bread to ease his hunger and wine to quench his thirst. Without hesitation the fisherman gives him both. Two mounted police arrive on the beach and ask the fisherman whether he has seen anybody. The fisherman, as the sun goes down, says nothing.

The story is forlorn; the tune, the voice, the rhythm are gregarious and reassuring. Between each two verses there’s a refrain: la lalala lalala la …

Michele extends his arms and a hundred listeners sing the refrain together. The medieval wall, visible behind them—between their shoulders and heads—turns to gold until the refrain ends. Then it returns to being stone.

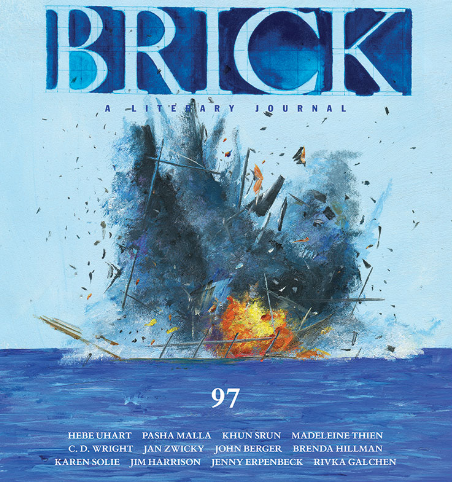

This essay appears in the current issue of Brick Mag.

Listen: John Berger talks to Paul Holdengräber on President Trump, the emptiness of American political commentary, desire, place, and how the hell to keep going.

John Berger

John Berger was a storyteller, essayist, novelist, screenwriter, dramatist and critic. He was one of the most internationally influential writers of the last fifty years, who has explored the relationships between the individual and society, culture and politics and experience and expression in a series of novels, bookworks, essays, plays, films, photographic collaborations and performances, unmatched in their diversity, ambition and reach. His television series and book Ways of Seeing revolutionized the way that Fine Art is read and understood.