Jill La Pointe on the Art—and Preservation—of Lushootseed Storytelling

Turning to New Technology to Revitalize Old Languages

When Haboo was first published 35 years ago, the dramatic art of traditional storytelling in many of our Native American communities was fading as younger generations became more adapted to mainstream culture and values. Recognizing the impact of cultural change taking place in their communities, my grandmother—like so many other elders—sought to gather and preserve as much traditional information and wisdom as possible. Every elder who contributed to this magnificent collection of cultural stories did so in hopes that someday future generations will once again appreciate the ancient art of storytelling.

Although much has changed over the years, there remains one unfortunate constant. Despite all the technological advancements since the first publication of Haboo, our communities continue to lose many of their beloved elders. As each year passes, we are left with fewer and fewer among us who can still recite the ancient stories and even fewer who can retell the stories in our traditional Lushootseed language.

Confronting this reality remains as critical to the survival of Coast Salish culture and language today as it was 35 years ago. The wisdom and teachings found in Haboo continue to offer a pedagogical resource that highlights a way of being in the world that we have strayed from, and they remain as relevant today as they have been for generations.

Growing up, my brother Jay and I heard our grandmother Vi taqʷšəblu Hilbert tell many of the stories included here over and over again. Staying true to who she was, she never explained the meaning or revealed the overall lessons hidden in the stories, but rather she instructed us to think about each story and ask ourselves, “What is the story trying to tell me?”

It wasn’t until years later that I gained a deep appreciation for the traditional art of storytelling, as I heard Grandma repeat to audiences everywhere, young and old, that “Lushootseed never insults the intelligence of a listener by explaining the story,” allowing them the same dignity her elders allowed her, to find their own interpretation and understanding.

Tribal communities throughout Puget Sound have language revitalization programs that use dedicated websites, YouTube, and smartphone apps to promote their cultural languages.

Over the years I have personally found this to be true insofar as my own encounters with the stories have remained fluid, growing with me, teaching me something new about myself as life brings me new experiences. I have been perplexed by some stories for years, only to realize that the lessons within are unveiled over time, bit by bit in accordance with my own physical and spiritual location in life at any given time.

The Lushootseed language and culture arose from the oral traditions of the Puget Sound Coast Salish people. It wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 70s that Lushootseed was developed into its current written form. It is important to appreciate this, given how easily technological advances allow us to access information. Today, finding the answer to nearly any question or learning about something new is as simple as asking Google, Alexa, or Siri. Since the advent of the internet and the rapid development of smartphones, nearly limitless information is available at our fingertips.

Nearly all tribal communities throughout Puget Sound have language revitalization programs that use dedicated websites, YouTube, and smartphone apps to promote their cultural languages. Any person with a computer or smartphone can start learning Lushootseed. I have no doubt that my grandmother would be not only amazed but excited about how technology has furthered preservation and promotion of the Lushootseed language and culture. However, it is also important to acknowledge how technology has changed the way we process information into knowledge that can enhance the quality of our lives.

Long before Lushootseed was developed into a written language, the ability to listen carefully and remember what you heard was intrinsic to the longevity and continuity of all important Coast Salish cultural teachings. Everything from family lineages and cultural traditions to spiritual and religious praxis, as well as our creation stories, which provide us an ontological understanding of our place and role in creation, were entrusted to the minds and memories of the listener, especially those who excelled in developing their minds, such as my grandmother’s Aunt Susie Sampson Peter.

For countless generations, the safeguarding of all this information depended not only on our ability to develop extraordinary memories but more importantly on our ability to listen attentively: “ləshuyud dcuʔkʷ(i)adx̌əč.” Make yourself single-minded (to avoid confusion). Moreover, development of these skills and abilities extended far beyond the preservation and transfer of information—they played a crucial role in our ontological purview.

Understanding our place and role in creation was shaped through our ability to listen and learn from creation in all its forms. My grandmother often repeated a common phrase she learned from her elders: “dᶻixʷ dxʷʔugʷusał tiʔəʔ swatixʷtəd.” The earth is our first teacher.

For countless generations our ancestors sought guidance from Mother Nature by listening carefully to all the teachings she had to offer, revealing to each person their vocation as well as moral guidance in how we are to conduct ourselves in the world. As each generation passes, our ability to listen carefully and remember accurately have faded. The skills of old continue to wane ever further as technology relieves us of the historical necessity to memorize important information.

What impact does the loss of such a rich and meaningful component of life have on the people or society?

Today, children are no longer required to sit patiently for hours listening to the old ones tell and retell us our cultural stories. No longer are children required to listen as the elders teach us our family histories and lineages or instill our spiritual and religious practices. All these vitally important teachings are x̌əčusədəʔ and xʷdikʷ, the special information that guides us throughout our lives.

What impact does the loss of such a rich and meaningful component of life have on the people or society? We are fortunate that our ancestors had the wisdom to foresee the tremendous change coming that would inexorably dismantle the world they once knew so well. Although it broke their hearts to know that these changes would affect every aspect of Puget Sound Coast Salish culture and life, they remained willing and determined to seize any opportunity to share their wisdom through what Swinomish elder Susie Sampson Peter called “a different canoe” (the tape recorder), so it could be captured and made available to us.

We are also blessed by the foresight of scholars such as Pamela Amoss, Sally Snyder, Thom Hess, and retired educator Leon Metcalf, whose fascination with the people and compassion for a dying culture led them to devote hundreds of hours traveling around the region, visiting different elders, and recording their wisdom, histories, and stories.

The stories in Haboo have so much to offer. They give each of us an opportunity to escape the seemingly unending technological bombardment of information and useless distractions streamed at us high-speed through our smartphones, laptops, iPads, and televisions twenty-four hours a day. I encourage you to take a break, shut down your laptop or iPad, turn off the TV, put your phone on silent, and allow yourself some time to sit quietly with at least one of the stories included here. Give yourself time to think about what unique meaning or lesson a story has for you. And if you feel ambitious, memorize it and share it with others.

__________________________________

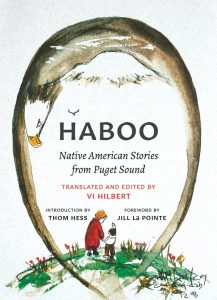

Haboo: Native American Stories from Puget Sound, Second Edition translated by Vi Hilbert, foreword by Jill La Pointe, and introduction by Thom Hess (University of Washington Press, 2020).

Jill La Pointe

Jill tsisqʷux̌ʷaɫ La Pointe is granddaughter of Vi taqʷšəblu Hilbert and holds a master’s of social work from the University of Washington. She is director of Lushootseed Research, a nonprofit organization dedicated to sustaining Lushoot- seed language and culture and to enhancing cross-cultural knowledge, wisdom, and relations.