Jenny Zhang on Reading Little Women and Wanting to Be Like Jo March

Looking to Louisa May Alcott's Heroine for Inspiration

From the moment I learned English—my second language—I decided I was destined for genius and it would be discovered through my writing—my brilliant, brilliant writing. Until then, I had to undergo training, the way a world-class athlete might prepare for the Olympics; so I did what any budding literary marvel desperate to get to the glory and praise stage of her career would do—I read and read and read and then imitated my idols in hope that my talents would one day catch up to my tastes.

At age ten, I gave up picture books and took the leap into chapter books, but continued to seek out the girly subjects that alone interested me. Any story involving an abandoned young girl, left to survive this harsh, bitter world on her own, was catnip to my writerly ambitions. Like the literary characters I loved, the protagonists in my own early efforts at writing were plucky, determined, unconventional girls, which was how I saw myself. They often acted impetuously, were prone to bouts of sulking and extreme mood swings, sweet one minute and sour the next.

I always gave my heroines happy endings—they were all wunderkinds who were wildly successful in their artistic pursuits and, on top of it, found true, lasting love with a perfect man. I was a girl on the cusp of adolescence, but I had already fully bought into the fantasy that women should and could have it all.

On one of my family’s weekly trips to Costco, I found a gorgeous illustrated copy of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, a book I had seen and written off every time I went to the library, repelled by the word women. Unlike the girl heroines I loved, a woman was something I dreaded becoming, a figure bound up in expectations of sacrifice and responsibility. A woman had to face reality and give up her foolish childish dreams. And what was reality for a woman but the life my mother—the best woman I knew—had? And what did she have but a mountain of responsibilities—to me, to my father, to my younger brother, to her parents, to my father’s parents, to her friends, to my father’s friends, to their friends’ parents, to her bosses, to her coworkers, and so on?

Her accomplishments were bound up in other people, and her work was literally emotional, as she was expected to be completely attuned to everyone else’s feelings. She worked service jobs where she was required to absorb the anger of complaining customers and never betray any frustration of her own. Her livelihood depended on being giving and kind all of the time, suppressing her less sunny emotions into a perpetually soaked rag that she sometimes wrung out on my father and me.

My mother had apparently wanted to be a writer when she was a young girl too. She loved reading novels and writing stories, but she continually repeated to me the same proselytizing refrain: everyone has to grow up and be responsible for others. And one day you will too, she forecasted; or, maybe she was trying to hex me. She wanted me to stop thinking of myself as some great exception. She believed the numbers didn’t lie—if something was popular, then that thing must be really good. That was her credo in life; if it applied to restaurants, it certainly applied to marriage and family. One had to do the expected thing, or else one was fucked.

Jo March has always been the fan favorite, the little woman everyone thinks herself to be, the clear front man of the four-piece band.

The odds were much higher that a young girl might one day find a husband and start a family of her own than become a famous writer. My mother believed no matter how miserable marriage and kids might be, it was guaranteed to be better than the misery of being childless and unpartnered. Better to be normal than to try to be extraordinary, she told me again and again.

Her and my father’s vision of womanhood was a nightmare to me. According to them, the best possible outcome was that I become a dentist. A dentist! Someone whose entire job was to look inside other people’s mouths. Whose line of work inspired fear, dread, and procrastination. I wanted to inspire action, write poems that transported the reader into the realm of magic, be the embodiment of Rilke’s you must change your life, and nothing less. When I nixed my parents’ ambition that I become a dentist, they suggested an alternative—law— quick to add they didn’t mean the lawyers on TV who went to trial and made impassioned arguments against the ills of racism and corporate greed, but the ones who sat around in the office all day completing paperwork.

That was the dream of the good life my parents had for me: a safe job where I didn’t have to overexert myself. Passion was bad. Routine, clerical tasks, low-risk paper-pushing that could be reliably repeated over and over again until I retired and lived out the rest of my life through careful budgeting of my retirement savings, was good. And of course, I was to find a man with the same values, marry, and procreate with him before my eggs dried up and I was nothing but a shriveled hag.

Why not just end life right here and now? I thought every time my parents brought it up. Better to die tragically young having experienced some shit than to make it to old age bored out of your mind. Perhaps there was someone who wanted the life my parents advocated for, could imagine being happy in it, could even take pleasure from achieving such milestones, but it wasn’t me. The picture my parents painted of my eventual ascension into womanhood was a prison. I wanted to stay a girl for as long as I could—it was the last stop before I had to annihilate all my dreams and get real.

When I finally read Little Women, it was out of boredom. My parents left me in the Costco book aisle for the better part of an hour, during which I devoured more than half the book. It was a paperback edition but the pages felt like heavy, quality card stock. The cover showed the March sisters in wide-brimmed hats trimmed with ribbon, delicately brandishing walking sticks. Meg was depicted in a Peter Pan–collared lavender dress with vertical white stripes, Jo in an unadorned navy dress with a priestlike white collar, Beth in a faded yellow pinstriped dress, and little Amy in a skyblue sailor dress.

Jo was the decidedly plain one, the one who clearly took no joy in having a beauty regimen. Under the bright warehouse lights, to my surprise, I was immediately enamored with the story of sisterhood and genteel struggle, enticed by the exoticism of a tale set against the backdrop of the Civil War—a period of time I could not fathom outside of history books—with its strange touchstones like only having enough money for lobster salad, scheming to possess a large quantity of pickled limes and secretly sucking them at school, and lunches composed of cold tongue. Though I had no sisters of my own, the story of four sisters raised by their self-sacrificing mother to be just as self-sacrificing despite repeated dips into the dramatic, self-involved throes of adolescence and puberty was incredibly familiar to me.

I should have identified with Jo, who possesses her creator’s best traits in spades (individuality, fearlessness, resourcefulness, and creativity), while the more trying aspects of Louisa May Alcott’s personality (the volatile temper and mood swings that would most likely be diagnosed as some kind of mood or personality disorder today) were mitigated by the author’s pen. After all, Jo March has always been the fan favorite, the little woman everyone thinks herself to be, the clear front man of the four-piece band, the one who hogged all the charisma and daring, the only one of the sisters whose vision of what a woman’s life should and could entail doesn’t seem so miserably dated today, the one character who has been cited by a roll call of prominent women writers as inspirational and as essential to their own artistic and feminist development, not to mention all the women whose names and lives were not famous enough to be recorded for posterity but who nonetheless were altered by Jo March.

In the context of literature written for young girls, Jo stands out. She is the rare fictional teenage girl who prefers the dirtiness of adventure to the cleanliness of order, who sees no romance in being tethered to a man, who rolls her eyes at the material inheritances promised by marriage, who would rather work her ass off to support her family through her writing than be saved by a man with money, who spends the majority of the book bucking the patriarchal fetish that women eternally sacrifice their own pleasure and efface their own desires in the service of men.

She is the character that most young girls who read Little Women are proud to identify with—and there I was, 12 years old, a self-professed “rebel” and “writing prodigy” who decided by the end of the first page that there was nobody I detested more than Jo March. Her boyishness, her impetuousness, her obliviousness, her agility at all types of masculine movement and her clumsiness at feminine preening, her utter lack of interest in the romantic attentions of men—in particular, her best friend and boy-next-door Laurie, who was a dreamboat to me, feminine in his name, teen girly in his adoration and unrequited love for Jo and even more so in his reaction to being rejected (not so vaguely threatening suicide, flinging his body around in despair, wailing dramatically, “I can’t love any one else; and I’ll never forget you, Jo, never! never!”)—her ideals, her stubbornness, her independence, her utter lack of giving a fuck when it came to adhering to gender norms, everything about Jo repulsed me.

Did other people see me the way I saw Jo—annoying, delusional, unwilling to grow up, stubbornly clinging to her childish dreams?

I should have identified with Jo, the only one of the sisters who not only wants to be a genius but by the end of the book is still in the running to be one. When playing a cheeky game of truth, Laurie asks Jo, “What do you most wish for?” to which Jo replies disingenuously, “A pair of boot-lacings.” Laurie calls her on her bluff, “Not a true answer; you must say what you really do want most,” and Jo fires back, “‘Genius; don’t you wish you could give it to me, Laurie?’ and she shyly smiled in his disappointed face,” reminding the reader that she’s the only one of the four March sisters who desires something that no man can give her.

What she desires is to burn with creativity, awaken the genius lying dormant in her soul. Later when Laurie confesses his love for her, Jo is baffled, makes it clear she does not reciprocate, and even goes so far as to say she doubts she’ll ever marry and give it all up for some guy. Laurie doesn’t buy it. No woman can be happy on her own; they all end up finding a man they are willing “to live and die for,” so why, why, why not him?

Rather than applaud Jo and her wherewithal to choose herself over the love of a good (and hot) (and wealthy) man at a time when women were structurally denied power and resources and had few options outside of marriage, I was horrified. How selfish, I thought, my criticism mirroring my mother’s jabs at me whenever I announced my intentions to be a writer, not someone’s mother. She’s never going to do better than Laurie! I fumed. What does he even see in her? I wondered. What made her think she could be free like a boy? What made a poor girl like her think she could act like a person with money?

Was my reaction because I saw parts of myself in Jo and didn’t like what I saw? Did other people see me the way I saw her—annoying, delusional, unwilling to grow up, stubbornly clinging to her childish dreams? It was through Jo that I finally tapped into the mindset of the very people I had been rebelling against: my parents. And in some sneaky way, it was Jo’s journey in Little Women that gave me insight into why my parents were so hell-bent on conforming. They had lived longer and survived more than I had and knew much more than I did about how much this world punishes those who don’t fall in line.

Growing up in Shanghai, I was a happy, extroverted, outgoing child. For the first four years of my life, I was the Amy March of my large, extended family. Everything I did was worthy of praise. Distant relatives and friends came from all over to see me, the golden child, the blessed baby. In the presence of company, I was serene and lovable. Once alone with my family, I was hyper. At nine months I was speaking in full sentences, by ten I was singing and dancing.

I loved to entertain, most of all by telling stories, and as with Jo, made-up stories were often more real to me than my actual lived life. Finding preschool to be a bore, I came home and told my family that our class had gone to the zoo and I had been chosen to ride on the back of an elephant. Like Jo, I loved to direct, putting on theatrical performances for my family filled with song and dance. I saw the world and everyone in it as a potential audience for my art.

The blithe, unearned confidence that radiated from my little soul abruptly died when I immigrated to New York. Suddenly language was stripped from me, no one clapped for me anymore when I spoke. My lack of proficiency in English was at best pitiful, at worst annoying. I had been muted; there was no longer any evidence I could entertain or dazzle. I was not yet five, and I had already undergone an identity crisis. The sweetness I had always been praised for was losing ground to something that little girls were not supposed to feel—anger.

By the end of my first year in America, I had passed out of ESL, but I hadn’t passed out of feeling self-conscious every time I spoke. In this new phase of my life, if I wanted to speak, I wrote it down instead. That was where I was the least inhibited, the least clumsy, that was the only space where I was not treated as accented, or worse—broken. I decided to give up on my dream of being a world-renowned entertainer; instead I would be a writer.

To say nothing of my delusions of grandeur, there was an even less noble reason motivating my pivot to the written word—I wanted to exact vengeance on everyone who had ever wronged me, underestimated me, or decided on the basis of my face that I was uninteresting, unworthy, and unremarkable. What better I’ll show you than to become a massively successful published author? What better revenge than to have the last word? Nothing lit a fire under my ass quite like wanting to prove my haters wrong. Nothing gave me a greater sense of power than to recast my life into fiction. Writing was a kind of alchemy; it had the power to turn the garbage of the past into gold.

It has been well documented that much of Little Women drew on Louisa’s actual family and upbringing. Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy were modeled after Louisa and her three sisters, and the girls’ mother, Marmee, was based on Abba, the overworked matriarch of the Alcott family who ran herself ragged to do what her husband, Bronson Alcott—an educator, writer, abolitionist, and reformer who started several progressive schools and a utopian agrarian community (all these enterprises foundered for one reason or another)—could not do: support the family and keep them afloat.

The family often went hungry and suffered through the brutal New England winters as a consequence of Bronson’s idealism, which led to practices such as refusing to work for wages, observing a kind of veganism that proscribed the growing and eating of root vegetables in favor of the consumption of “aspiring vegetables” that grew up toward the sun, and no wearing of cotton, silk, or wool because they were products of slave labor and capitalism. The poverty that plagued Louisa’s upbringing (in the first 25 years of her life, her family moved more than 30 times) was given a much rosier treatment on the page.

The suffering the March girls underwent while their father was away serving as a chaplain in the Civil War was honorable and bearable. In the first chapter they give up their Christmas breakfast to a poor, starving family of six and happily return to their home to bulk up on their own goodness in addition to some bread and milk. Our hearts are meant to be warmed by this anecdote of Christmas cheer, but in reality the Alcotts themselves often relied on handouts from others, and often went through long stretches with nothing to eat besides bread, water, and the occasional apple.

Louisa herself was prone to frequent mood swings and an unpredictable temper. She was such a troublesome child that she was sent away to live with her grandfather for the final stretch of Abba’s difficult pregnancy with Lizzie, the third daughter and the inspiration for Beth. By contrast, Jo’s moods are depicted as charming, her emotional states never so violent that they alienate the reader. Her enthusiasm and excitability never reach the level of out-of-control mania.

The one time we are given the opportunity to dislike Jo comes after Amy, in a bratty fit, tosses Jo’s writing in the fireplace. We are told it’s a book Jo has been working on for years, so it is easy to understand why Jo would be devastated and refuse to talk to her sister. But when a thoroughly ashamed and contrite Amy tries to win Jo’s forgiveness, following Jo and Laurie as they go ice-skating, Jo purposefully pretends not to see Amy tagging along behind them and doesn’t convey Laurie’s warning that the middle of the ice is unsafe for skating. Amy immediately plunges through the ice into the frozen river. Jo and Laurie pull Amy out and by nightfall, all is fine again. Amy is forgiven. Jo is forgiven.

I wonder now, no longer the little girl I was back then, who would not stand for my mother’s criticism of my father.

Nonetheless, after Amy’s brush with death, Jo breaks down to Marmee and confesses her fear that she may never be able to cure her temper. “You don’t know; you can’t guess how bad it is! It seems as if I could do anything when I’m in a passion; I get so savage, I could hurt any one, and enjoy it. I’m afraid I shall do something dreadful some day, and spoil my life, and make everybody hate me. Oh, mother! help me, do help me!”

Marmee reassures Jo that they are not unalike; that, in fact, her temper used to be just as bad. “I’ve been trying to cure it for forty years, and have only succeeded in controlling it. I am angry nearly every day of my life, Jo; but I have learned not to show it; and I still hope to learn not to feel it, though it may take me another forty years to do so.”

It reads like a passage from a different book and Jo, rightly so, reacts in utter surprise. Nothing in the chapters preceding suggests Marmee is anything but saintly in her patience and superhuman in her restraint with her children. And no matter how badly things go for the March family, Marmee is always looking out for others who are worse off. Has it all been a tightly managed façade? Is the beauty of womanhood learning to manage one’s anger every day of one’s life? How is not expressing anger different from repressing it?

We never learn exactly what Marmee is angry about, and because of it, as a child, I didn’t buy it. I saw it as artifice, an authorial decision to make us think Marmee is the perfect woman—capable of passion and high tempers but never so much that it interferes with her goodness. Real anger is volcanic and active. There is no keeping it down.

My own mother often flew into rages on account of our financial woes, which she sometimes attributed to my father (he was the one, after all, who made the decision to leave China in search of whatever hazy notion of a “better life” was available in America), and other times attributed to dumb, bad luck. Behind the closed doors of our home, my mother bemoaned the state of our lives some nights and other nights swung sharply in the other direction, bursting with unexplained optimism, reiterating to me how everything that had happened thus far in her life had been fortunate. How as a young girl she loved to sing and dance and act and even had producers knocking at her door with promises to make her the next “Chinese Shirley Temple,” but my grandmother refused and sent all the producers and agents away, unwilling to let her daughter fall into the sleazy sex and drug den that was the entertainment world, and rather than feel resentful at my grandmother for denying her the chance to pursue her passions, she was grateful, truly grateful! Or so she said.

Abba Alcott, the real-life matriarch of the Alcott family, was less even-keeled than her fictional counterpart, did not contain her anger as successfully, and was even more tireless and overworked as a result of her husband’s repeated failures to provide for the family. While supporting her husband’s experimental utopian commune, Fruitlands, which, like all his ventures, eventually failed, Abba wrote in her diary, “There was only one slave at Fruitlands . . . and that was a woman,” evincing more than a hint of bitterness.

Louisa observed a similar unjust dynamic, that the men of Fruitlands “were so busy discussing and defining great duties that they forgot to perform the small ones.” Staying true to one’s ideals always comes at a cost, and in the case of the Alcotts, it was often Abba and her daughters who paid it. In another diary entry, Abba wrote, “a woman may live a whole life of sacrifice and at her death meekly say, ‘I die a woman.’ But a man passes with a few years in experiments in self-denial and simple life, and he says, ‘Behold, I am a God.’”

Perhaps Louisa didn’t need to detail what Marmee is so angry about nearly every day of her life. To be a woman is to know anger. To be underestimated, treated as inferior, have one’s concerns classified as minor, to do all the work and receive none of the glory—how could one not feel angry? And yet in order to be a good woman who stands a chance at being loved and accepted, back then and still very much so now, one has to learn, as Marmee advises Jo, not to show it, even better not to feel it. Anger in a woman runs the risk of being pathologized, penalized, criminalized. A woman is supposed to bear the violence of patriarchy—both the bloody and the bloodless forms—with unflappable cheeriness.

Why must we learn to control it? I wonder now, no longer the little girl I was back then, who would not stand for my mother’s criticism of my father, who considered my mother’s capacity for rage an unforgivable defect, who only saw how tirelessly my father worked to give our family a good life, and who dismissed the sacrifices my mother had made, including leaving the only family, friends, and country she had known to move to a foreign land where she did not speak the language and where she would never have the opportunity to advance beyond being someone’s assistant or someone’s secretary, working full-time while also being a full-time wife and mother, and not only supporting my father in obvious ways but also supporting him emotionally, taking over the duties of staying in touch with family overseas (not just hers but his as well), welcoming my father’s parents into her home not once, not twice, but five separate times, each time lasting over a year, all the while managing her own loneliness, isolation, culture shock, and depression.

How could I blame her for bouncing between having faith in the world and sinking into inconsolable despair? How could I blame her for lashing out? As an adult, I see now we are hardest on the people who mirror the shadowy parts of ourselves, the parts we don’t want to see.

_______________________________________

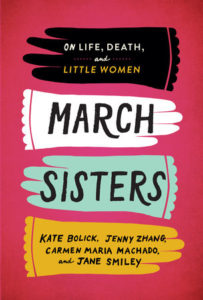

Excerpted from “Does Genius Burn, Jo?” by Jenny Zhang from March Sisters: On Life, Death, and Little Women by Kate Bolick, Jenny Zhang, Carmen Maria Machado, and Jane Smiley. Copyright © 2019 by Jenny Zhang. Published by Library of America. Used with permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Jenny Zhang

Jenny Zhang is a poet and writer living in New York City. Her debut collection, Sour Heart, won the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.