James Joyce’s Dublin, a Microcosm of the World

The Streets in Ulysses Are the Streets of the Everyman

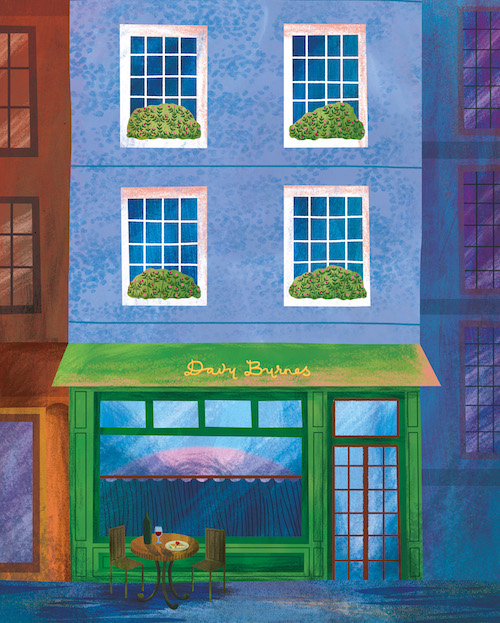

The pub is warm and beery. Grog glasses—drained, foam stained—scatter sticky veneer. Red-wine lips, hoppy breath, a slurry of slurring; laughter like gunfire, craic-ing off the wood panels, mirror walls and ranks of whiskey bottles. Bar talk is of theology and adultery, literature and death, soap and sausages. Everything and nothing, discussed or daydreamed over a quick cheese sandwich. A nothing old day. But the stuff of life—infinitesimal yet essential—all the same . . .

James Joyce’s Ulysses—variously considered the most momentous, accomplished, infuriating and unreadable book in the English language—is the ordinary made extraordinary. It’s a modernist reworking of Homer’s Odyssey, but while the Ancient Greek poem tells of Odysseus’ incident-packed return from the Trojan War, Joyce makes an epic out of a single, unremarkable day.

Ulysses follows Leopold Bloom, a Jewish ad canvasser for The Freeman’s Journal, as he wanders around Dublin on June 16, 1904. He attends a funeral, goes to the pub, ducks into a museum (to avoid the man sleeping with his wife), pleasures himself by Sandymount Strand, enters the red-light district. The novel is a chaotic stream of consciousness, performing stylistic acrobatics to try to render the human experience. But it is grounded in the streets of Dublin. Joyce, writing from self-exile in Paris, slavishly researched the physicality of the city. Though he seldom returned, he remained tethered: “When I die,” he once said, “Dublin will be written in my heart.”

At the turn of the century the city was changing. The well-to-do had moved to the suburbs as the overcrowded center decayed. Dublin had some of Europe’s worst slums; almost one in every four children died before their first birthday. A Celtic Revival was promoting Irish culture and language while in politics the Irish Parliamentary Party was pressing for Home Rule (rather than independence). But more radical movements were fermenting, and the Great War (1914–1918), Easter Rising (1916) and IRA violence were imminent. Though published in 1922, the “action” of Ulysses predates this tumult. Joyce concerns himself, not with the struggles of nations but rather the little battles an Everyman faces, everyday. Dublin becomes a microcosm of the world.

Joyce’s geographic diligence makes it possible to trace Bloom’s footsteps. Start at No. 7 Eccles Street, Bloom’s home, where he fries kidneys and contemplates his wife’s infidelity. The building was knocked down in the 1960s but a plaque marks the spot and the original doorway is preserved within a fine townhouse on North Great George’s Street, now the James Joyce Centre.

O’Connell Street lies around the corner, a fashionable address in Georgian times, though faded by the 1900s, and damaged during the Easter Rising. No more the horse-drawn cabs and clanking trams; a stroll down its leafy central mall these days is accompanied by car din and a mishmash of architectural styles. Bloom wouldn’t have passed Joyce, who now leans nonchalantly in bronze at the corner with North Earl Street, but he did note the monument to Irish leader Daniel O’Connell—”the hugecloaked Liberator’s form”—which stares across the River Liffey.

Bloom buys Banbury cakes to feed the wheeling gulls as he walks over the wide span of O’Connell Bridge, the divide between dingier north Dublin and the more affluent south. This crossing takes you and Bloom into the heart of Dublin, home to the Bank of Ireland (originally the Irish Parliament building), prestigious Trinity College (where Catholic Joyce didn’t go), the National Library (where he frequently did). It leads to narrow, shop-lined Grafton Street, still gay with awnings, where locals and outsiders alike still come for the craic—Dublin’s social essence.

Bloom is hungry when he hits Duke Street. His first choice, The Burton—establishment of “pungent meatjuice, slop of greens”—is no more. But Davy Byrnes pub, a traditional boozer, first opened in 1889, still serves Gorgonzola sandwiches and glasses of Burgundy (Bloom’s lunch of choice), providing a tangible taste of Joyce’s sometimes indigestible masterpiece.

__________________________________

From Literary Places. Used with permission of White Lion Publishing. Copyright © 2019 by Sarah Baxter.