Jaboozie Turns Me On to Deep Cuts

A Prose Poem by Eric Gansworth for the Fourth of July

It’s the Fourth of July, and we shouldn’t really be celebrating, but even Indians can’t deny the sweet forever taste of charbroiled hot dogs and ears of corn roasted till the kernels are crisp on the outside, exploding with flavor once you bite into them, surrounded by family in all its random variations, drawn home like magnets aligned to the same polar orientation, locked sturdy.

This year, I have found my way into the trunk of a giant Plymouth driven by Jaboozie’s mother, stuffed in with her and her brothers, and my cousins and whoever else is willing to share space with the jack and the bald spare tire. We ride the dark back roads off the Rez to reach the upper escarpment, keeping the trunk tied almost closed with clothesline, so no cops see us riding where we are not supposed to. It’s tricky since the car itself is already stuffed with adult Indians, which is, by this virtue alone, already begging to be pulled over and given an impromptu investigation, detained as long as the officer feels like asking questions.

We make it to the hill overlooking Artpark, the new place where they launch fireworks, competing with the city display that’s been around forever. The blanket we’d hidden beneath inside the trunk is now beneath us as we watch the sky. Jaboozie’s mom has the radio playing. Even though she’s risking the battery, she feels we need the luxury every once in a while. It is the beginning of FM radio, and I am learning new songs I’ve never heard before, what the DJs call Deep Cuts. Though that label sounds painful, there is no denying the song transporting me to the Black Hills, home of the Dakotas, and men named Rocky, Doc, Dan, and a woman who must have been from a Rez out there, as she went by Magill, Lil, and Nancy, at the same time.

When it’s over, I shush everyone on the blanket with me, but instead of the DJ identifying that song, something new comes on, a drawback of the current FM format. The assortment of cousins and friends crowded onto the blanket laugh at my panic, but Jaboozie tells me it was from the Beatles’ White Album, and assures me we can play it when we get back to the house after the finale, when they let you know it’s time for you to leave by blasting a hundred explosions at once, filling the night sky with smoke and echoes.

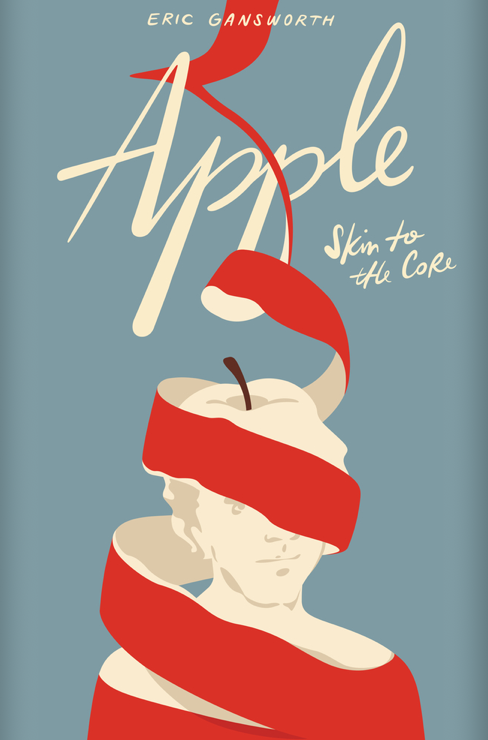

At the house, Jaboozie’s mom drops us off while all the adults head out to do Rez laps, telling us not to wait up. Freddie, Jaboozie’s older brother, doesn’t seem to mind that he’s just been drafted to keep an eye on all of us. As promised, we go up and turn on his record player. He has retrieved the album from his mother’s collection. The cover is so blank it looks like a mistake. But Freddie has me run my fingers across the cover, as he puts the album on and lines it up, so I can feel The BEATLES in raised letters. This looks and sounds like no Beatles album I’d ever encountered. The photos included show them hairy and uncombed, like guys you might see walking up and down Dog Street looking for a ride uptown. Even the label is different from all of our albums, the rainbow border and drawing of the Capitol, replaced by the shiny green skin of an apple on one side, its crisp, pale interior, core and seeds exposed on the other.

Freddie says it was their first taste of freedom, that they’d chosen to make their own record label instead of being controlled by an outside force. He says he heard they chose an apple because it was like Eve in the Garden of Eden, gaining knowledge after her first bite. He starts the album with the first song on side one. Though the song I want to hear, “Rocky Raccoon,” is a dozen songs later, on the other side, Jaboozie and her siblings insist there is only one way to listen to The White Album, from front to back. These kids from down the road have more music knowledge than I do and I intend to get an education tonight.

My world is changed forever, as if I have bitten the apple, myself, understanding this is a glimpse into the possibilities, and as we listen to the last side, they all grin, crowded around the speakers, watching my face when “Revolution 9” begins. It is not really a song, instead seeming like a nightmare made of sound, and though I am terrified of the mysterious voices saying strange things, moaning, screaming, the sounds of flames popping on burning wood, crowds chanting, horns blaring, when it is over, I want to hear it again. We sit around, listening to the entire thing from the beginning, making up ridiculous scenarios where we can’t escape this song (?), agreeing we’d grow slowly unbalanced. We forget we are kids, alone in a house, not sure where our adults are, when they will come back, and not really caring. We understand the future is always like that flat, blank plain of this album cover, filled with mystery that we will never really see until it is right on top of us, confronting us with our own lack of experience.

_________________________________

From Eric Gansworth’s forthcoming collection, Apple: (Skin to the Core), available from Levine Querido in October.

Eric Gansworth

Eric Gansworth, Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ, (Eel Clan) is an enrolled Onondaga writer and visual artist, raised at the Tuscarora Nation. Lowery Writer-in-Residence at Canisius College, his books include Extra Indians (American Book Award), Mending Skins(PEN Oakland Award), and Apple (Skin to the Core), Longlisted for the National Book Award, and included in Time Magazine’s 10 Best YA and Children’s Books for 2020, and NPR’s Book Concierge. Portrait by Dellas.