It’s Time We Added Full Credit Pages to Books

Maris Kreizman on the Importance of Acknowledging the Labor That Goes in a Single Title

The perks were few and far between when I was an editorial assistant in book publishing in the early aughts. Mostly I did the job for the books and the proximity to authors and the occasional access to free leftover sandwiches from some lunchtime meeting or other (I was also lucky to do this work when it was still possible to rent a room in a Manhattan apartment on a $30,000 salary). But there was one reward that cost nothing, but that made me feel rich: a credit in the Acknowledgments section in the back of a book I worked on.

“I was here,” I still think, whenever I flip to the page in, say, Maggie Nelson’s 2007 memoir The Red Parts (yes, this is a brag) where my name is mentioned. How lovely it is to be seen and appreciated. How lovely it was to have something concrete to show my mom.

Unseen and unacknowledged labor is as central to book publishing as Republican politicians being overpaid to write books that no one except their own political action committee actually buys. Labor issues abound in the industry, from low pay and insufficient overtime to a lack of diversity that still hasn’t been meaningfully addressed.

For the most part wage increases have barely kept up with the cost of living, and I don’t have stats on rates of employee turnover, but I have to believe they’re high, at least for entry- and mid-level employees who find no room for advancement after a couple of years. Yet HarperCollins remains the only one of the Big Five publishing houses to have an employee union—we have so much work left to do.

Why shouldn’t books also feature an ending credits page where we could call out the Best Boy of books, whoever that is?When we watch movies we are given the chance to see the names of every single person who worked on the film, far beyond leading actors and writers and producers. As the credits roll, the audience can decide whether to register the names of the workers who did less glamorous but still important jobs from Best Boy (still the best job title of all) to caterers and personal assistants.

Why shouldn’t books also feature an ending credits page where we could call out the Best Boy of books, whoever that is? The industry is so much deeper and robust than simply publisher and editor and agent (hell, it took this long to give translators cover credit). Why not thank the managing editor or the designer who made the book look the way it does, the subsidiary rights team that facilitated foreign sales, the publicity assistant who sent out a million copies of the book?

Some generous authors have chosen to explicitly thank everyone who worked on their book, even the ones they never got to actually meet. Shea Serrano, Anthony Oliveira and Molly McGhee have all requested full lists of credits in the back of their works. I interviewed McGhee for my podcast on the publication of her 2023 debut novel, Jonathan Abernathy You Are Kind, and as a former assistant in publishing, she has been outspoken about labor issues in the industry. She chose to add credits, she told me, because “I just really wanted there to be physical evidence that someone put their time into this book and I wanted them to be able to keep it and for it to be special.”

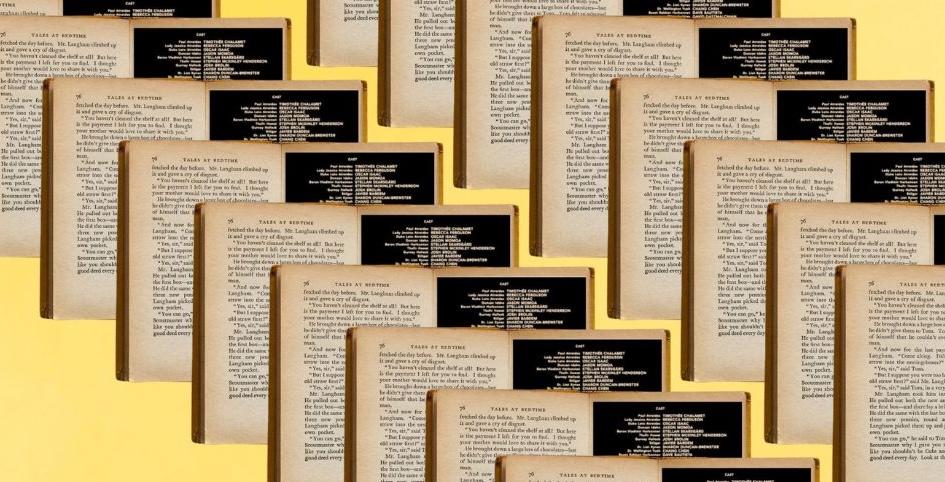

But it shouldn’t be up to individual authors to track down the names and titles of every single employee who had a hand in making their book. I’m encouraged to see that individual imprints like Avid Reader Press and Crown have begun to standardize the process of adding a credits page to the back of each and every book they publish. I hope other imprints and other publishers will see their example and be inspired.

There is an enormous amount of invisible work that is done in publishing. Adding a standard credit page would not be an answer to the various and copious labor problems in the industry, but it could be a nice (and cost effective) start in making publishing staff feel more valued. At the very least, publishers could easily facilitate a few more ways to make someone else’s mother feel proud.