Is Trump the Inciting Incident for a True Democratic Hero?

On Plot, Republican Politics, and the Power of Classical Narrative

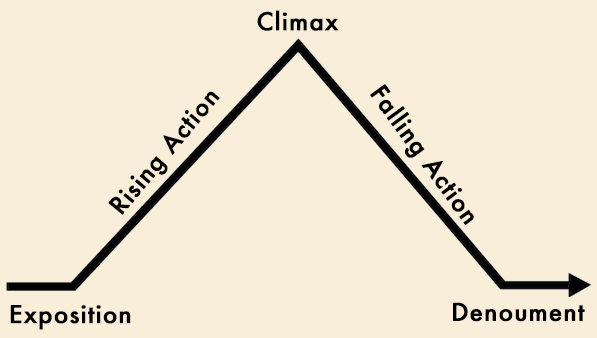

The day after the election, my students I faced each other around a table with stunned, helpless expressions and chocolate. I thought it was a good idea to bring chocolate, and I went for the good kind: bittersweet 78 percent, and salty chocolate-covered almonds. I said, “Let’s think about this in craft terms.” We had been talking about Freytag’s pyramid, also known as the Fichtean pyramid, also known as Aristotle. This structure is primordial in us, and has been reiterated through the centuries, this recognition of a story pattern that has a visceral satisfaction for humans:

It’s so basic, so simple, that you know it even if you haven’t studied it. It’s in every action movie you’ve ever seen, almost every TV show. There is a status quo (described through exposition), a time of stasis where there are underlying desires but action isn’t taken. And then something happens—an Inciting Incident—and the protagonist is forced to act on his desires. The protagonist is opposed by an antagonist. And there are obstacles thrown in the path of the protagonist, who struggles mightily, struggles more, overcoming obstacle after obstacle, battling the antagonist, until a triumph.

I asked, “What is the Republican inciting incident?” My students are smart and thoughtful, and they went back to World War II. “After that, there was so much prosperity,” one person said. The 50s, suburbia, Leave it to Beaver. I pointed out that there was a parallel narrative then—that of social justice: Lynching, Jim Crow, Rosa Parks, Civil Rights, Women’s Rights, the Vietnam War, Gay Rights.

Two narratives, then.

So that was the status quo, I said. But what was the inciting incident, the actual event, for the Republican narrative? The inciting incident in a classic narrative, I reminded them, had to feel like a matter of life and death. Even if it was an emotional death, the protagonist had to feel, If I don’t act I will die.

I had an idea, but I wondered if my age is what made me see it. I thought of when I was younger, in college, and only knew the Vietnam War in vague, historical ways. But I’d lived the narrative arc I had in mind. I knew it as well as I knew my own story.

“Reagan?” asked one, hesitantly. “The Great Recession?” asked another. “But those are generalized. They aren’t events,” I said. An inciting incident is an event, a physical moment in time where something happens that’s so big, so transformative, that it is where the story begins. The implicit sentence, always, after an inciting incident is this: So he was forced to act or die. Just as the implicit sentence at the end of the story, after the climax, after the resolution, is this: And nothing was ever the same after that.

Then I just told them.

I was sweeping the floor of our empty living room, my new husband still in bed. Most of our things had already been loaded into the moving van. I turned on the TV and saw the towers falling. Oh my God, I said. Oh my God. I imagine now millions of voices saying the same thing, all of us at once. Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God, over and over, a collective litany of despair and horror and shock, not a scream but a helpless, horrified chant. Oh my God.

I remember that day for the silence. I had an errand and foolishly went to the mall. It was closed, of course, and the parking lot deserted, as if the shoppers had been raptured. At the dog park that evening, we stood in stunned silence. “Hear that?” someone said. He meant, nothing. Do you hear nothing? No planes. No cars. No distant freeway roar. The entire world had stopped.

For the Republicans, this was their inciting incident. It was a galvanizing, unifying, perfect inciting incident, what writers call a powerful narrative engine, one that could drive the plot forward in a propulsive, inevitable climb to the climax. The protagonist was the U.S.—us—as represented by our hero, the president. The antagonist was the terrorist; in those days, Bin Laden. And the obstacle? The obstacle was the Democratic party, the liberals, the foolish, soft, blind, sand-under-their-feet, relativistic people who weren’t willing to take a stand and fight for freedom, for our very lives. They weren’t the antagonists, because they were not what the Republicans were fighting. They were just obstacles. Get out of the way and let us save you, said the hero.

It is devastatingly elegant. It is indestructible. The protagonist is killed, but another takes his place for the sequel. ISIS arrives, beheading Christians and burning them alive. The hero is cast out, his office occupied by the soft, relativistic Democrat, and the story does not pause. The pyramid is supposed to operate this way. As the plot accelerates upward, the obstacles are supposed to become more apparently insurmountable. The protagonist is replaced in the sequel. Paul Ryan, Ted Cruz, the Tea Party—they are the hero in the wilderness, calling out, warning of danger. There are terrorists out there. They are coming for us. The hero realizes that the danger is wider than he expected; the antagonist’s conspiracy goes deep, involves dangers creeping over the border, arising from within, destroying our economy, murdering our children. They have infiltrated us. They will kill us all. And the obstacle, now in power, is blind to it.

There is always a moment in a thriller where the hero seems defeated. But he rallies. He makes a new plan. He never gives up, because if he does, we could all die.

The Republican protagonist is Odysseus, battling for home. (Let’s ignore for the moment the fact that his men all die). He is Captain Ahab, hunting down the whale. (Ditto.). He is Gatsby, fighting for Daisy’s love. (Ditto again. There is a pattern of martyrdom in this narrative).

What is the Democratic narrative? They aligned with that other status quo after World War II. It is a narrative of justice for all. It is a noble narrative, but it lacks structure. In its amorphous, inclusive nature, it has no engine. It is what editors call episodic. What is the inciting incident? The next moment of injustice. All moments of injustice. Every time everywhere when someone isn’t treated fairly. Who is the antagonist? Every perpetrator of injustice. What is the obstacle? Injustice. What action must be taken? The perpetrators must be persuaded to be fair. It is, by its very nature, a narrative that abhors force. You cannot fistfight someone into fairness. We teach our children this fact.

The Democratic point of view isn’t even the protagonist of the dramatic narrative. The narrator is not the hero. He is the observer, the one who says, Look here. This is happening to this person. We must help this person. The Democratic point of view is Nick in The Great Gatsby. It is Ishmael. This is not my story, they say. But we must understand that there are people in this world who have not had the advantages we have had, and we must help them. Often, in my classes, students ask of third person narration, “But who is telling the story? Why are they telling the story?” Democratic narrator is a third person voice, telling a story that is not even his own.

People love story. It is human nature. We attach ourselves to the most compelling stories, and hold on to them tightly. We identify with the heroes, and imagine we could be that hero too. Their cause becomes our cause. Their fears become our fears. And the Republican narrative is so elegant, so beautifully, classically constructed that it compels with ferocity. And now we have reached its climax. Trump has been elected. The hero has triumphed. Nothing will be the same after that.

And everywhere, people stand in front of their television sets, millions of people, saying, Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.

It seems another inciting incident has arrived.

Goldberry Long

Goldberry Long is the author of the novel Juniper Tree Burning. Her forthcoming novel is under contract at Simon and Schuster. Her work has appeared in Colorado Review, New Orleans Review, The Rumpus, and Poetry International. She lives in California with her family, where she teaches fiction writing at the University of California, Riverside.