Inside the Secret Facility Where the USSR’s First Cosmonauts Trained

Stephen Walker on the Vanguard Six

January 18, 1961

Military Unit 26266, 41 kilometers north-east of Moscow

Deep in a birch forest in the Shchyolkovsky District north-east of Moscow, far from the main highway to the city and hidden from prying eyes, stood a small, old-fashioned two-story building half-buried in the snow. Here the snow lay even more thickly than it did eight thousand kilometers away in Washington. It piled on the building’s steeply pitched roof, on the overhanging porch of its front door, on the tangled branches of the birch trees, accentuating the heavy silence of the forest.

Apart from its curious location, there was nothing especially remarkable about the building itself. Perhaps its very anonymity helped to disguise its true purpose. For this nondescript edifice sitting in the middle of the forest in fact housed one of the most secret institutions in the USSR. Its code name was Military Unit 26266, but it was also known by its initials TsPK or Tsentr Podgotovki Kosmonavtov: the Cosmonaut Training Centre. And it was here on this particular Wednesday, two days before President Kennedy’s inauguration in Washington and the day before Alan Shepard’s selection as America’s first astronaut, that six men were competing to be the first cosmonaut of the Soviet Union, if not the world.

Like the Mercury Seven astronauts in Langley, Virginia, the six men were also sitting in a classroom. But the similarities ended there. They were all obviously younger than the Americans, in their twenties and not thirties. They were all wearing military uniforms, not casual Ban-Lon shirts. And with the exception of Gus Grissom, they were all shorter, short enough to fit inside the Vostok spherical capsule replacing the thermonuclear warhead on top of the R-7 missile that they all hoped one day soon to fly in space.

And unlike the Mercury Seven too, these six men were not waiting for somebody to arrive. Instead, they were sitting an examination. Later that afternoon they would each be interrogated by a committee responsible for their training. The same committee had already assessed their performance the previous day in a crude simulator of the Vostok capsule. This simulator, the only one in the USSR, was not located in the forest but in a palatial pre-revolutionary building in Zhukovsky 45 kilometers south-east of Moscow named LII: otherwise known as the Gromov Flight Research Institute. For up to 50 minutes, under the watchful eyes of their examiners, each of the six men had practiced procedures in the mock-up of the Vostok’s cockpit on the second floor of what had once been a tuberculosis sanatorium under the jurisdiction of the People’s Commissariat for Labour.

The building in the birch forest where the men were now sitting their examinations was the first structure in what would become, over time, a vast, heavily guarded complex closed to the outside world and dedicated solely to the training of the USSR’s cosmonauts. In 1968 it would change its name to Zvyozdny Gorodok—Star City—but that was still far in the future. Until then the area itself was known as Green Village, a nod perhaps to the acres of trees that shrouded it. When the new Cosmonaut Training Centre was established on January 11, 1960, by order of the commander of the Soviet Air Force, Chief Marshal Konstantin Vershinin, Green Village was chosen as the best site for its construction. It had many advantages: it was shielded by its forest but not far from Moscow. It was also only a few kilometers from Chkalovsky air base, the largest military airfield in the Soviet Union. And it was close to OKB-1, the secret design and production plant at Kaliningrad where Arvid Pallo’s battered Vostok had been returned only the week before the men sat these examinations—and where the next-generation human-carrying Vostok capsules were also being built.

The Soviet space program had ambitions to conquer the cosmos, or at least that part of it encircling the earth, and they needed the manpower to do it.

The six men had been training for ten months since March 1960, although the classroom building had only been in use since June. They had also used other anonymous centers in Moscow and continued to do so. In years to come, many of them would move into specially built residential blocks in Star City, but in January 1961 they were living near the Chkalovsky air base in basic two-room apartments with their wives and children where they had them, or in even more basic bachelors’ quarters where they did not. These were a far cry from Alan Shepard’s comfortable house in Virginia Beach’s leafy suburbs or indeed anything the American astronauts and their families would have willingly put up with, but by Soviet standards they were privileged accommodations. Meanwhile nobody in Chkalovsky outside their closed circle knew why the six men were there or what they were training for. Nor did their parents, nor their friends, nor their former colleagues in the air force. Even their own wives were not encouraged to ask too many questions. Unlike the Mercury Seven, who were famous throughout America if not the world, the six men existed only in the shadows.

And there was another key difference from the Mercury Seven. These six were not the only cosmonauts being trained. There were fourteen more. In a selection process that was even more ruthless than that undergone by the American astronauts, twenty men had been chosen from an initial pool of almost 3,500 military pilots. The Soviet space program had ambitions to conquer the cosmos, or at least that part of it encircling the earth, and they needed the manpower to do it. All twenty men had begun their training in the spring of 1960, just two months after Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had urged his chief space engineers that they “should quickly aim for space. There’s broad and all-out levels of work in the USA and they’ll be able to outstrip us.” By then the Mercury Seven had already been training for almost a year. The Soviets needed to catch up fast and these twenty cosmonauts were the answer. But other than those broad hints in the tightly controlled press about “Soviet Men” soon visiting space, the facts would be either hidden or deliberately misrepresented. The rockets, the capsules, the designers, the engineers, the training centers and launch locations, and of course the cosmonauts themselves—all of it would remain behind closed doors.

By the autumn of 1960 the Soviet manned space program had become a top national target, not least because back then NASA appeared to be aiming to send an American into space as early as December that year. To speed things up and prioritize training on the single simulator, a shortlist of six front-runners was filtered from the original twenty. They would fly first before the others. In essence, they were the premier league team that would take on the Mercury Seven. To those permitted to know, this group of six was given a name. Perhaps in deliberate imitation of the Mercury Seven, they were called the Vanguard Six.

________________________________________________

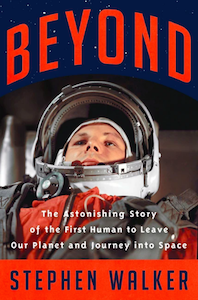

Excerpted from Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space. Used with the permission of the publisher, Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Stephen Walker.

Stephen Walker

Stephen Walker was born in London. He has a BA in History from Oxford and an MA in the History of Science from Harvard. His previous book was Shockwave: Countdown to Hiroshima, a New York Times bestseller. As well as being a writer he is also an award-winning documentary director. His films have won an Emmy, a BAFTA and the Rose d’Or, Europe’s most prestigious documentary award. Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space is his latest book.