Inside the Rooms Where 20 Famous Books Were Written

From The House of Mirth to Go Tell It on the Mountain

We often talk about literature as if it were some kind of magic thing—like it could be conjured without effort, if only we could arrange ourselves in a certain fashion, eat the right breakfast, perform our ablutions just so, organize our desks like our favorite writers, copy their daily rituals. Unfortunately, writing is hard, no matter what you do. When you’re working, you have to be a mercenary, taking whatever space you can get, doing whatever works on that day. But when you really love a novel, there’s still something mysteriously satisfying about seeing where it was made—it’s kind of like making a pilgrimage to where your lover was born and raised. It doesn’t mean anything, exactly, because you don’t believe in magic, and yet it does. At the very least, it’s fun. So for our mutual enjoyment, I present the places where some of literature’s most beloved works were written: some beautiful, some dark, all apparently capable of inspiring greatness.

Connie Hum for Connvoyage

Connie Hum for Connvoyage

Edith Wharton famously did most of her writing in bed (longhand, in the mornings, with her dogs). In her bedroom at The Mount, she wrote the book that would make her famous, The House of Mirth, as well as Ethan Frome, dropping each finished page to the floor for her secretary to pick up, organize, and type.

Jana Crowne for Cuba Holidays

Jana Crowne for Cuba Holidays

In Finca Vigía, his house in Cuba, built in 1886 by the Catalan architect Miguel Pascual y Baguer, Ernest Hemingway wrote seven books, including For Whom the Bell Tolls, A Moveable Feast, and The Old Man and the Sea, among others. He wrote in the library, which Roxana Robinson describes as “a long, pleasant, high-ceilinged room, lined with tall bookcases. In front of the windows is The Desk, huge and magisterial, about ten feet long and three feet wide, and curved like a boomerang. It’s made of dark polished wood, with carved supports at each end. Hemingway sat in the center, the ends curving forward.”

Pera Palace

Pera Palace

Like Ernest Hemingway and Ian Fleming, Agatha Christie frequented the Pera Palace Hotel in Istanbul, Turkey. Her favorite room was 411, and it was here that she reportedly wrote the bestselling Murder on the Orient Express. It’s been refurbished since that time, of course, and updated with Agatha Christie-themed art. On the plus side, while the real Orient Express no longer runs, the hotel still stands, and you can actually stay there, in the very same room as your favorite crime writer.

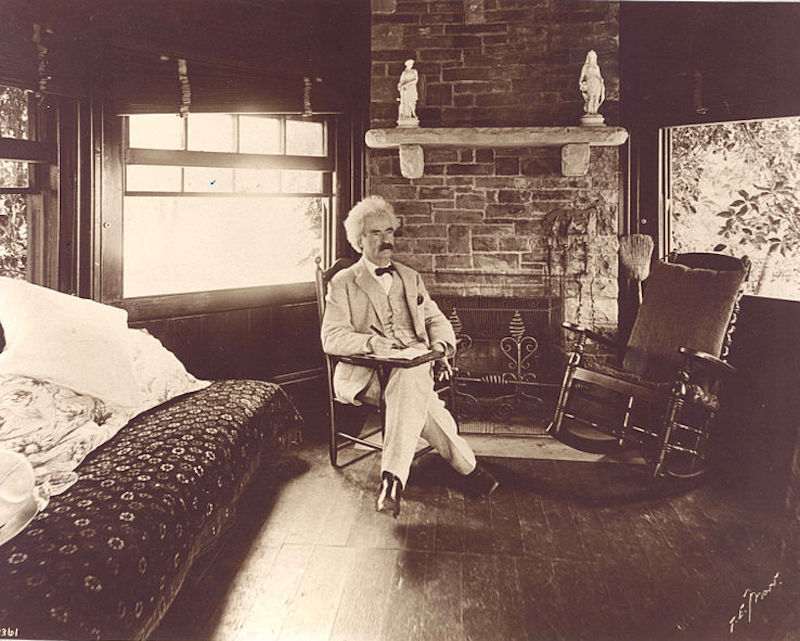

Though he grew up in Missouri and eventually moved to Connecticut, Mark Twain spent every summer in Elmira, New York, at his in-laws’ estate. He wrote a lot, in an octagonal writing hut that his sister-in-law built just for him. Here, he wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, among other things. In a letter, Twain described it like this:

Though he grew up in Missouri and eventually moved to Connecticut, Mark Twain spent every summer in Elmira, New York, at his in-laws’ estate. He wrote a lot, in an octagonal writing hut that his sister-in-law built just for him. Here, he wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, among other things. In a letter, Twain described it like this:

It is the loveliest study you ever saw. It is octagonal with a peaked roof, each face filled with a spacious window, and it sits perched in complete isolation on the top of an elevation that commands leagues of valley and city and retreating ranges of distant blue hills. It is a cozy nest and just room in it for a sofa, table, and three or four chairs, and when the storms sweep down the remote valley and the lightning flashes behind the hills beyond and the rain beats upon the roof over my head—imagine the luxury of it.

You can visit it today—it’s now on the campus of Elmira College.

Roald Dahl also had a writing hut, and in fact it was inspired by a third writing hut—Dylan Thomas’s. He wrote all of his books in the hut after it was built in the mid-1950s—by his friend Wally Saunders, for about £80 (according to 10 Wondrous Writing Hut Facts), including Matilda, The BFG, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. He didn’t even let Quentin Blake hang out there.

After being exiled from France, Victor Hugo bought a house on Guernsey, an island in the English channel. There, sitting in his writing room (called the Crystal Room), looking out at gorgeous, light-filled vistas, he wrote his dark and depressing classic Les Miserables. The rest of the house is beautiful too.

UCLA Powell Library

UCLA Powell Library

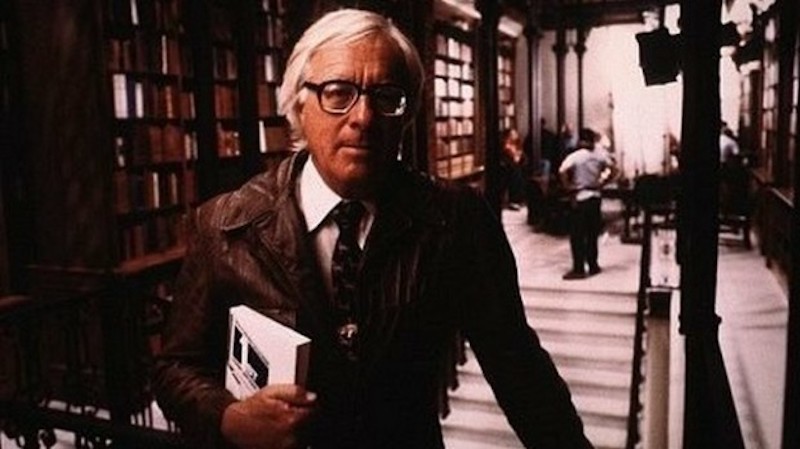

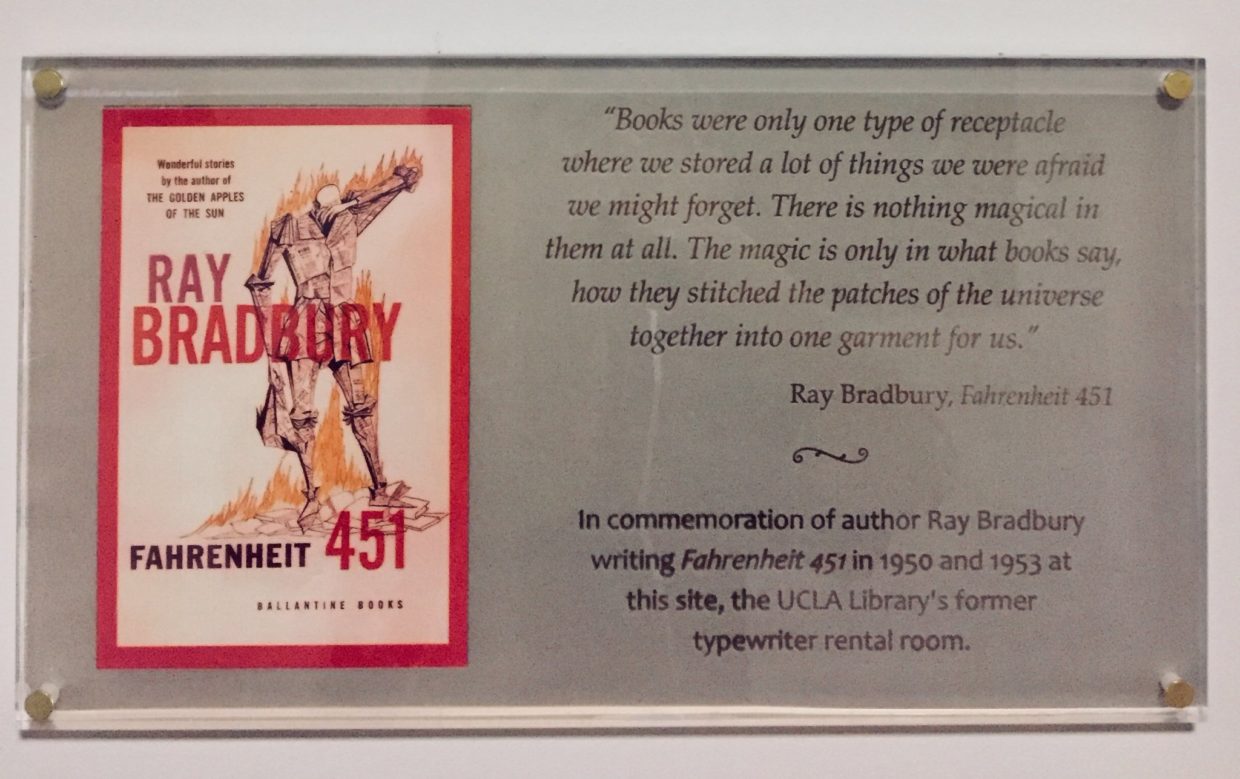

Ray Bradbury wrote Fahrenheit 451 in the typewriter rental room in the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library. “In 1950, our first baby was born, and in 1951, our second, so our house was getting full of children,” Bradbury said in a 2005 interview.

It was very loud, it was very wonderful, but I had no money to rent an office. I was wandering around the UCLA library and discovered there was a typing room where you could rent a typewriter for ten cents a half-hour. So I went and got a bag of dimes. The novel began that day, and nine days later it was finished. But my God, what a place to write that book! I ran up and down stairs and grabbed books off the shelf to find any kind of quote and ran back down and put it in the novel. The book wrote itself in nine days, because the library told me to do it.

He wrote the short story “The Fireman” in 1950 (it cost him $9.80 in dimes) and then returned to expand it into his most famous novel in 1953. The space has been remodeled and now houses the Office of Instructional Development Administrative Offices, but there’s a plaque, so I’m counting it.

Parisian cafés are famous for their outdoor tables and people-watching, but James Baldwin wisely retreated to the upstairs room at Café de Flore to write the first draft of Go Tell It On the Mountain undisturbed, except by waiters bringing more coffee and Cognac.

Eamonn McCabe

Eamonn McCabe

“I have worked at this desk for the past 47 years,” J.G. Ballard told The Guardian in 2007. “All my novels have been written on it [Crash, The Drowned World, Empire of the Sun, etc.], and old papers of every kind have accumulated like a great reef. The chair is an old dining-room chair that my mother brought back from China and probably one I sat on as a child, so it has known me for a very long time. A Paolozzi screen-print is resting against the door, which now serves as a cat barrier during the summer months. My neighbour’s cats are enormously affectionate, and in the summer leap up on to my desk and then churn up all my papers into a huge whirlwind. They are my fiercest critics.” As for the painting, it’s a forgery—a copy of Paul Delvaux’s lost painting “The Violation,” which Ballard commissioned from the artist Brigid Marlin. “I never stop looking at this painting and its mysterious and beautiful women,” he says. “Sometimes I think I have gone to live inside it and each morning I emerge refreshed. It’s a male dream.”

John Spinks for T Magazine

John Spinks for T Magazine

Julian Barnes in the North London room where he’s been working for 30 years, and where he wrote The Sense of an Ending and other books. “It is on the first floor,” he says, “overlooking the tops of two prunus trees, which flower before they leaf, so that in a lucky year there can be both snow and pink blossoms on bare branches.”

Bob Cummings

Bob Cummings

I couldn’t find a picture of the exact room, so I’m cheating a bit here, but this is the place where William Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying. It was a coal power plant for the University of Mississippi and the town of Oxford, and Faulkner worked there as the overnight supervisor during the summer of 1929 (though why anyone in that town continued to employ him is beyond me). “I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheelbarrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler,” he wrote in a 1932 introduction to the Modern Library edition of Sanctuary.

About 11 o’clock the people would be going to bed, and so it did not take so much steam. Then we could rest, the fireman and I. He would sit in a chair and doze. I had invented a table out of a wheelbarrow in the coal bunker, just beyond a wall from where a dynamo ran. It made a deep, constant humming noise. There was no more work to do until about 4 A.M., when we would have to clean the fires and get up steam again. On these nights, between 12 and 4, I wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks, without changing a rod.

If only there was a wheelbarrow to show you—unfortunately the University of Mississippi tore down the whole building in 2016.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.