Among the many coincidences that can be found in the files of the covert history of Operation Long Jump are the parallel events that occurred on July 26, 1943. For it was on the very day when the two spy chiefs had their first meeting at the Eden Hotel that Adolf Hitler also began to tread in similar territory. He, too, had inaugurated the planning for an adventurous, and by all reasonable expectations, impossible mission. Further, in what would prove to be an even more significant concurrence, in his opening move that summer afternoon Hitler had reached out, just as Schellenberg had when he’d started, to the head of the Oranienburg special action school—SS captain Otto Skorzeny.

“Could it be connected with Operation Franz?” Skorzeny would recall wondering in the first moments after he’d received the perplexing news that he’d been summoned to the Wolfschanze, Hitler’s secluded headquarters deep in the woods of East Prussia. But he swiftly dismissed the notion; it seemed implausible that the Führer would want a personal briefing on a run-of-the-mill mission like the one in Iran. Instead, his “brain was plagued with useless queries,” and no good answers. And on that sunny late-July afternoon when he boarded the Junkers Ju-52 parked at Templehofer airfield, he was gripped by a nagging fear: in the Reich the bill for past sins, whether real or merely perceived, might be presented at any moment.

There were twelve seats on the plane and no other passengers, and he had no idea whether that was reason for encouragement or not. But there was a cocktail cabinet at the front of the aircraft, and he helped himself to a glass of brandy. Then another for good measure. Skorzeny’s nerves began to soothe, the plane lifted off, and he tried to prepare himself. He would be standing for the first time face-to-face with Adolf Hitler, the Führer of the Reich and the supreme commander of the Wehrmacht.

A big Mercedes was waiting when the Junkers touched down. A drive through a thick forest led to a checkpoint, and after credentials were presented the car continued along a narrow road edged by birch trees. Then a second barrier, another demand for identification, and a short drive to a tall barbed wire fence. When the gate opened, the car followed a winding drive surrounded by low buildings and barracks; the structures were covered with camouflage nets, and trees had been planted on the flat roofs of many of the buildings for additional concealment. From the air, it would look like just another Prussian forest.

It was dark when he arrived at the Tea House, a wooden building where, he was told, the generals took their meals. Skorzeny was brought to a drawing room spacious enough for several wooden ta-bles and upholstered chairs. A bouclé carpet, dark and plain, covered the planked floor. He was made to wait, but in time a Waffen-SS captain appeared. “I’ll take you to the Führer. Please come this way,” he requested.

Another building. Another well-furnished anteroom, and this one bigger than the previous one. On the wall was a pretty drawing of a flower in a silver frame; he guessed it was a Dürer. Then he was led through a hallway into a large, lofty space. A fire burned in the hearth and a massive table was covered with piles of maps. A door abruptly opened, and with slow steps Adolf Hitler entered the room.

“It is absolutely essential that the affair should be kept a strict secret.”Skorzeny clicked his heels and stood at attention. Hitler raised his right arm out straight, his well-known salute. He was dressed in a field-gray uniform opened at the neck to reveal a white shirt and black tie. An Iron Cross First Class was pinned to his breast.

When he finally spoke, it was in a deep voice. “I have an important commission for you,” Hitler announced. “Mussolini, my friend and our loyal comrade in arms, was betrayed yesterday by his king and arrested by his own countrymen.”

Skorzeny quickly tried to recall what he had read. Benito Mussolini, the Fascist dictator who ruled Italy with a heavy hand, had arrived for an audience with King Victor Emmanuel of Italy. No sooner had he sat down than Victor Emmanuel had bluntly announced that the Supreme Council had asked the king to command the army and take over the affairs of state, and he had accepted. A shaken Mussolini left the palace, only to be confronted by a captain of the carabinieri, who directed him to a Red Cross ambulance. The rear door opened—to reveal a squad of police armed with submachine guns. At gunpoint, the now former Italian dictator was shoved inside. The ambulance drove off, its destination a secret, as was Mussolini’s fate.

Back in the present, Skorzeny listened as the Führer grew more animated. “I cannot and will not leave Italy’s greatest son in the lurch. He must be rescued promptly or he will be handed over to the Allies. I am entrusting to you the execution of an undertaking which is of great importance to the future course of the war. You must do everything in your power to carry out this order. You will need to find out where Il Duce [literally, ‘the Duke,’ the title the Italian Fascist movement had bestowed on Mussolini] is, and rescue him.”

At attention, Skorzeny kept his eyes locked on Hitler. He felt himself being drawn in, carried along, he’d remember vividly, by “a compelling force.”

The Führer went on without pause. “Now we come to the most important part,” he said. “It is absolutely essential that the affair should be kept a strict secret.”

The longer Hitler spoke, the more Skorzeny fell under his spell.

“At that moment,” the SS captain would explain, “I had not the slightest doubt about the success of the project.”

Then the two men were shaking hands. Skorzeny bowed and made his exit, and as he walked out the door he could still feel Hitler’s eyes boring into him.

Yet once he was back alone with his thoughts in the Tea House, Skorzeny’s previous confidence turned to sand. His nerves were “in a pretty bad state” and hundreds of questions seemed to be screaming in unison in his head. So he forced himself to concentrate, to think like a soldier. “Our first problem,” he told himself as he worked to regain control, “was to find out where Mussolini was.” Only no sooner had he focused on that problem than another immediately rose up. “But if we managed to find him, what next?” he asked himself. “Il Duce would certainly be in some very safe place and extremely well-guarded. Should we have to storm a fortress or a prison?” His ranging mind “conjured up all sorts of fantastic situations,” and none of them were consoling.

Still, he reined himself in. Drawing on years of discipline, he started to make a list. He’d need fifty of his best men, and they all should have some knowledge of Italian, he began. Set them up as nine-man teams, that would be manageable. Then he considered weapons and explosives. Since it was a small force, it would need the greatest possible firepower, he told himself. But in the next moment he ruled out heavy artillery; they might have to drop by parachute. Instead, he decided, they’d have to make do with only two mounted machine guns for each team. The others would be armed with just light machine pistols, but that was a lethal-enough weapon when fired by a marksman. And explosives? Hand grenades, of course. And while thirty kilograms of plastic explosives should be plenty, he also made a note to get the British-manufactured bombs that the SS had scavenged in Holland; they were more reliable than anything distributed to the Wehrmacht. All sorts of fuses, too, both long and short running, would be needed; there was no way of predicting the battle plan, so they’d better be prepared for any eventuality. Then they’d need tropical helmets and light underclothing; you wouldn’t want to be traipsing around Italy under the burning summer sun in long johns. And food, of course, had better be requisitioned. Rations for six days and emergency rations for three more should keep the men going. If that wasn’t enough, well then, the chances were that they would be on the run from the Allies in enemy territory, and eating would be the last thing on any of their minds.

When Skorzeny had completed his list, he found the radio room so he could send it off to his headquarters in Berlin by teletype. Then he returned to the cot that had been made up for him in the Tea House. It was well after midnight, the end of an exhausting day, but he could not sleep. “Turning over and over in bed,” he’d say, “I tried to banish thought, but five minutes later I was wrestling with my problems again.” The more he picked away at the mission, “the poorer seemed the prospect of success.”

Unknown to Skorzeny, on that same long night across the Reich in Berlin, Schellenberg tossed restlessly in his own bed as he mulled remarkably similar tactical problems. He, too, could reach only a despairing conclusion.

It was a demanding time. He left it to his adjuncts to keep the force in fighting trim, ready for whatever physical demands the mission might require. As for himself, Skorzeny concentrated on a single objective: finding Mussolini. There was no point in planning an assault until they knew where Il Duce was held captive. He needed to solve one mystery before he could even begin to grapple with the next.

“All sorts of rumors were flying about as to where Mussolini could be found,” he discovered, and he had no choice but to chase after each of them. A grocer had heard there was “a very high-ranking prisoner” on the remote penal island of Ponza. An Italian sailor turned informant was certain he was interred on a warship cruising off the port of La Spezia. A postman sighted Il Duce in a heavily guarded villa on the island of Sardinia. And Canaris had gotten into the hunt, too, insisting the Abwehr had received reliable intelligence establishing that Mussolini was being kept in a makeshift prison on a thin strip of an island off Elba. But none of these panned out. After three futile weeks, Skorzeny fumed, “we were back at the beginning.” And when Hitler summoned him once again to reiterate that “my friend Mussolini must be freed at the earliest possible moment,” his already low mood nose-dived even deeper. For an egotist like Skorzeny, failure was the worst fate that could be imagined.

But as he was preparing to give up all hope, he received an intelligence report detailing a car accident involving two very highranking Italian officers in the Abruzzi mountains. What were they doing up there? Skorzeny wondered. It was a long way from the fighting, or, for that matter, from any military installation.

When he followed this trail, Mussolini drew closer. And at last a plan for his rescue started to take shape.

There were twelve gliders, and the idea was that they would swoop in for their soft landings as if on cat’s feet, and that way the teams would have the benefit of surprise. It wasn’t a carefully worked-out plan, and there were too many uncertainties, too many unknowns, a dozen things that could easily go wrong. Skorzeny knew his chances of pulling it off were “very slim.” He doubted that his men could overpower the guards before Mussolini would be executed. But he had considered all the other possibilities, and this was the only one that held even a trace of promise.

The more he thought it through, the more the element of surprise became essential.Il Duce was being held, he had finally verified to his satisfaction, in a ski resort perched on top of a nearly seven-thousand-foot Apennine mountain. A single cable car ran from the valley up to the summit, and a detachment of heavily armed soldiers stood guard around the station, while carabinieri had blocked off the approaching road. The Hotel Campo Imperatore, where Mussolini was being held, might just as well have been a fortress: solid brick, four stories, and at least a hundred rooms—and Il Duce could have been in any of them. Added to that, about 150 soldiers, as best as the intel reports could estimate, had dug in on the mountaintop and were guarding the hotel and its only guest. With a nod of professional praise, Skorzeny had to give the Italians credit. If he had wanted to keep someone safely hidden away, this was what he might’ve done. No, he conceded, this was even better.

His admiration for the Italians’ shrewdness grew as he tried to work out a rescue plan. He quickly ruled out a ground assault. Making their way up the steep mountainside would be a running battle, and with the enemy firing down from fortified positions, a losing one. Surprise would be the first casualty. There’d be such a racket of gunfire and explosions, he imagined, that it’d be heard in Rome. The Italians would have all the time they needed to scurry off with Mussolini, or, equally likely, shoot a bullet straight into his head.

The more he thought it through, the more the element of surprise became essential. The mission would be a gamble, and this would be, he said, his “trump card.” So he had considered a parachute attack, his commandos jumping from planes. But the Luftwaffe experts ruled it out. At that altitude, in the thin air, the men would drop from the sky like lead weights, slamming into the ground. And those would be the lucky ones—jagged rock formations lay scattered all about the mountaintop, projectiles as sharp as swords.

By default, gliders would have to do. Only that required a big, level landing field where the craft could come down after their towing planes had cut them loose. The closest thing the surveillance photos offered was a foggy glimpse of a triangular meadow not far from the hotel. The Luftwaffe wise men quickly vetoed that, too. A glider landing at this altitude without the assurance of a well-prepared landing ground was sheer folly, they insisted. At least 80 percent of the troops, according to their prediction, would be wiped out when the light craft careened about the rocky meadow. There wouldn’t be a sufficient force remaining to storm the hotel.

Skorzeny took his time before responding. “Of course, gentlemen,” he said at last with a careful politeness, “I am ready to carry out any alternative scheme you may suggest.”

“This action has made the deepest impression throughout the world.”In that way, the decision was made. And on September 12, 1943, at about one in the afternoon, the gliders began to drop out of the sky and come down in a rush, the wind shrieking. A gust caught one of the craft, and it fell as if shot out of the sky, pounding into a rocky slope and smashing into pieces. Another two were blown far off course. And Skorzeny’s glider came down in a nose-first crash that bounced the shattered machine about as if it were a stone skimmed across a pond. But when he pulled the bolt and climbed out of the exit hatch, he saw that he was only about twenty yards from the hotel.

Of the fight that ensued, there’s not much to say, because it was not much of a fight. The shocked sentries put up their hands in surrender on Skorzeny’s command, and the team rushed into the entrance hall. On instinct, Skorzeny chose a staircase and leaped up it three steps at a time. He started flinging doors open, and on the third try he found Mussolini guarded by two Italian soldiers, who were hustled out of the room. The entire assault had taken four minutes at most.

A small Fiesler Storch plane, with its single propeller and long wings, had landed on the now secured mountaintop, and Mussolini climbed into the only rear seat. There was no room for another passenger, but Skorzeny was not about to abandon his charge (or the triumph that would be his when he presented his hard-won prize to Hitler). He somehow managed to fit himself into the cramped space behind Il Duce. The overloaded plane had to struggle to rise into the air, but just when it seemed that it had reached the end of the plateau and was poised to nose-dive into the gully below, it caught a gust and climbed high into the blue sky.

Three days later Skorzeny and Mussolini were having midnight tea with the Führer at the Wolfschanze. Hitler awarded the SS commando the Knight’s Cross and promoted him to major (Sturmbannführer). “I will not forget what I owe you,” the Führer promised him in a burst of emotion.

Paul Joseph Goebbels, the Reich minister of propaganda, made sure that the world, too, would not forget what Skorzeny had accomplished. The front pages of newspapers throughout Germany offered up suspenseful accounts of the daring mission, and for once the Nazi reporters could stick to the facts, because the truth was sufficiently extraordinary. A short newsreel film was produced, widely shown to applauding audiences, and Skorzeny’s handsome smiling face became quickly known all over Germany. Even the papers in the United States and England had to admit that the Nazis had pulled off a remarkable success. Their headlines announced that Skorzeny was “Europe’s Most Dangerous Man.”

But arguably it was Goebbels himself, writing in his diary, who best caught the full impact of the moment. “This action has made the deepest impression throughout the world,” he wrote. “There has not been a single military action since the outbreak of the war that has shaken people to such an extent or called forth such enthusiasm. We may indeed celebrate a great moral victory.”

Of course, Schellenberg also found himself contemplating what Skorzeny—the very man he’d selected to train the SS commandos for the Iran missions—had accomplished. In his mind he followed a direct line that led from a raid on an impregnable Italian mountaintop to the assassination of the Allied leaders. And it left him filled with hope. He now had the evidence that encouraged him to feel that despite all odds the impossible could indeed be accomplished. If Skorzeny could manage to pull off one miracle, well, why not another? For the first time Schellenberg found himself believing that it could be possible to kill FDR, Churchill, and Stalin in a single covert operation—and in the process alter not just the outcome of the war, but also the peace.

Yet before too long, all his usual misgivings attacked. The imponderables were enormous: He had no idea where the three-party conference would take place. Or when it would occur.

Without this crucial intelligence, nothing would ever be possible. If he didn’t know the time, if he didn’t know the place, if he didn’t know any of the specific operational pitfalls that lay in his path, then no team of commandos, even one led by the likes of Skorzeny, would have a chance. If, if, if. A litany of ifs, each one a question without an answer.

__________________________________

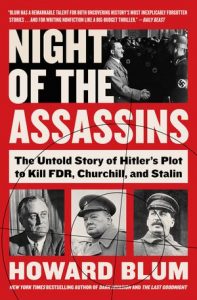

From Night of the Assassins by Howard Blum. Used with the permission of Harper. Copyright © 2020 by Howard Blum.