The house is quiet now, lanterns extinguished, the family settled for the night, parents in the bedroom, daughters on old quilts on the main floor. As revenge for the stolen fish, Jamini has claimed Deepa’s place by the window, where it is coolest. Deepa grumbles her way to the second-best spot at the other edge of the room. Priya lies between them. Such things matter little to her.

She wakes to a panicked banging, someone outside shouting, Daktar-babu, shouting, Emergency. Deepa groans and pulls her pillow over her ears, Jamini sits up in fright, Priya flings open the door. Their desperate night-visitor is a young fisherman. His wife has been in labor since morning, but the baby will not budge. The midwife says she can do nothing more.

Tousle-haired, in rumpled pajamas, Nabakumar goes into the bedroom to fetch his medical bag. Bina frowns. “It sounds challenging.”

His voice is somber, his words clipped. “It does. Do not wait up for me.”

Bina sighs. After traveling all day, Nabakumar needs his sleep. And the case will bring little, if any, money. Still, she climbs out of bed and puts a couple of clean old saris into a bag. After a moment she adds a baby quilt.

Priya has followed Nabakumar. “Please let me come with you! It might help to have an extra pair of hands.”

Bina is scandalized. “An unmarried girl cannot be at a birthing.”

Priya is afraid Nabakumar will agree. Not because it is unseemly— such thoughts do not occur to him—but because he does not like to cross Bina. Also, he might not think Priya would be of use. Until now she has assisted with only simple tasks at his Ranipur clinic, stitching up a cut, lancing a boil, prescribing malaria medication. But he nods: Bring lanterns. Two of them. Hurry. She realizes that he expects more trouble than he can handle on his own.

They walk through the sultry night to the fisher neighborhood. Narrower paths, shacks leaning drunkenly against one another. The man—his name is Hamid—leads them to the smallest one. Dim light of a smoky lamp, a pregnant woman panting on a mat. The frightened midwife tells them the baby’s heartbeat is very faint.

“The umbilical cord might be tangled,” Nabakumar says. He disinfects his hands, examines the patient. “I’ll have to cut her open. Chloroform.”

Priya pushes away fear and follows instructions. Press the chloroform rag against the patient’s face until she slackens, clean the belly with antiseptics, tell Hamid and the midwife to hold the lanterns steady. Hand Nabakumar the instruments he calls for, scalpel, scissors, clamp. Do not flinch when blood wells dark from the incision in the woman’s belly. The woman moans. Calm, calm. More chloroform, count out the drops with a steady hand, hold the weeping flesh apart. Nabakumar lifts out a baby boy. Cut the cord serpent-coiled around the infant’s neck. Hold his feet, slap his back, hand him to the midwife when he cries, no time for complacency, help to stitch up the woman, clean the blood, tear strips from Bina’s saris. Bandage the wound, administer a penicillin injection, tell the overwhelmed Hamid what he must do until the doctor’s next visit.

Then she remembers. She rummages in the bag and hands the baby quilt to Hamid.

The fisherman’s eyes well up, he runs reverent fingers over the soft cloth patterned with butterflies. It is one of Bina’s simplest, but Priya sees that he has never owned anything so fine. He accompanies them back in silence, but at their door he weeps again, trying to gather words for his gratitude, trying to hand Nabakumar a handful of coins.

Nabakumar waves them away, but he does not make Hamid feel small.

“Bring us some fish when the catch is good,” he says.

Hamid nods. He walks away, shoulders straighter, head high.

Priya thinks, How much I have to learn from Baba about doctoring. About human decency.

At the threshold of the sleeping house, she gathers courage. “When I took the baby from your hands, knowing that it might have died but for us—I have never experienced anything as exhilarating. Did I do well?”

“You did wonderfully. Calm and efficient—the perfect assistant.”

She is light-headed with tiredness, terrified with hope. “Will you let me attend the medical college in Calcutta, then? I want to be a doctor. It is my dream.”

Baba looks away. “I am too tired to discuss this right now.” This is not the whole truth. He forestalls her each time she brings up the subject. But she is his daughter, inheritress of his stubborn genes. She will not give up.

__________________________________

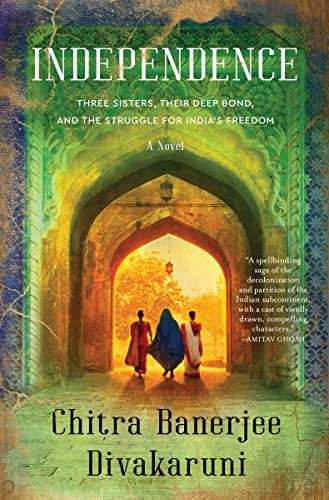

Excerpted from the book INDEPENDENCE by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. Copyright © 2023 by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. From William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.