Happy New Year, readers. 2022 had its ups and downs, along with some very good books. But now that you’ve read all the books last year had to offer (right?) it’s time for a brand new list.

Here are the books Literary Hub editors are most looking forward to (so far!) in the months to come.

JANUARY

Deepti Kapoor, Age of Vice

Riverhead, January 3

A whirlwind, madcap adventure to rival your favorite crime tv binge, set in a contemporary India suffused with money, violence, and power, and following a colorful cast of characters: gangsters, journalists, fraudsters, servants on the come-up, servants on the come-down. Read for a very good time. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Allegra Goodman, Sam

Dial Press, January 3

Allegra Goodman’s latest novel features that tricky thing: a child protagonist. The book follows Sam from ages seven to 19 as she struggled with her father’s erratic behavior, her mother’s turbulent relationship, and the universal mandate to grow up. I love a coming-of-age story told in the moment when the author has a deft hand, and given Kevin Wilsons’s ringing endorsement—he called SAM “one of the most evocative and tender examinations of youth that I’ve ever read”—I have no doubt that Goodman pulls it off. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

Parini Shroff, The Bandit Queens

Ballantine, January 3

One of the most talked-about debut novels of the year lives up to the hype and then some. The story of Geetha, a tough-but-wounded young woman in a remote Indian village who, after her abusive husband disappears, gains a reputation as a black widow. These rumors prove somewhat beneficial to Geetha in her desire to be left alone…until other women start approaching her for help in disposing their own shitty husbands. Uproarious, tender, and at times quite harrowing, with razor-sharp dialogue and a truly magnificent cast of characters, The Bandit Queens is a darkly hilarious delight of a novel. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

Sean Adams, The Thing in the Snow

William Morrow, January 3

The HarperCollins Union has been on strike since November 10, 2022. Literary Hub stands in solidarity with the union. Please consider donating to the strike fund.

The Thing in the Snow is bizarre in the best way possible. A small group of workers at a remote arctic facility spend their days testing chairs and counting desks, keeping the huge research station in moderately working order. One day, they spot a suspicious thing in the snow just outside. It seems to move. It must have an agenda. But what could it possibly want?! –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Matthew Dennison, Roald Dahl: Teller of the Unexpected: A Biography

Pegasus, January 3

Where were you the first time you read one of Roald Dahl’s stories for adults, and realized he wasn’t quite as sweet and innocuous as he comes off in his children’s books? I had the jarring, ultimately horrifying, experience of reading Switch Bitch when I was 20, barely believing it was written by the same man who’d come up with such beloved tales as Matilda and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. When you look up this specific book of stories, Switch Bitch, Wikipedia will tell you it is “linked by themes of rape by deception”, and the cover is something you just have to see for yourself. Horrible!

All to say, Matthew Dennison has taken on the monumental task of encompassing the contradictions within this man who offered our childhoods such whimsy, though when you read those same children’s stories a little more closely, had a predisposition to cruelty and punishment that is more apparent when you read his adult oeuvre in tandem. It’s biographies like these that are all the more exciting for the conflicts within, no man is straightforward, but Roald Dahl is undoubtedly a figure that calls for deep excavation. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Cheuk Kwan, Have You Eaten Yet? Stories from Chinese Restaurants Around the World

Pegasus, January 3

Writer and filmmaker Kwan explores the Chinese diaspora by taking a journey through Chinese kitchens—and sharing the stories of those who populate them—all over the world. A book about identity, social history, global ethnography, changing politics, economic realities, and the strength of family, all wrapped up with that most important of cultural touchstones: food. –ET

Franz Kafka, tr. Ross Benjamin, The Diaries of Franz Kafka

Schocken, January 10

The first time I read The Metamorphosis, I was in high school. We all found it deeply troubling. Also, sort of fun. We didn’t yet know that you were allowed to do something like that in literature, that your main character could just wake up as some sort of vermin one morning! How exciting! How cruel! What must’ve happened to the writer to make him even conceive of such a conceit? And, more importantly, if you could peer inside the mind of the genius that brought us that f*cked up story, wouldn’t you want to? This new translation of Franz Kafka’s diaries, translated by Ross Benjamin, promises to offer an intimate glimpse of the artist at work, the man behind the curtain. From 1909 to 1923, these diaries entries convey daily observations, wild dreams, the seeds of stories, and (the best for last) “passages of a sexual nature that were omitted from previous publications.” Sign me up! –Katie Yee, Associate Editor

Leigh Bardugo, Hell Bent

Flatiron, January 10

I loved Leigh Bardugo’s first Alex Stern book, Ninth House—basically the perfect book for adults who miss the fantasy novels of their youth. Anyway, the literary fiction world does sequels now, and I’m here for it. Time to go back to the most terrifying version of Yale you’ve ever imagined. –ET

Laura Zigman, Small World

Ecco, January 10

The HarperCollins Union has been on strike since November 10, 2022. Literary Hub stands in solidarity with the union. Please consider donating to the strike fund.

Two newly divorced sisters move in together for the first time in 30 years, reacquainting themselves with each other, and in result, with their joint childhood and all its unresolved baggage. Joyce and Lydia grew up with a sister with special needs, Eleanor, and parents who were gung-ho disability activists, who possibly gave too much time to the cause and not enough to their children. It’s up to Joyce and Lydia, this much time later, to understand the years spent together in that house long ago, their grief from Eleanor’s premature death, and the mysteries that still revolve around their specific history—domestic and personal, nuanced and poignant, Small World offers a new map of how to move forward from a heavy past. –JH

Jordan Harper, Everybody Knows

Mulholland, January 10

In this pitch-dark version of Chinatown in the #metoo era, a publicist who specializes in getting scandals to go away finds herself in possession of a secret too big to bury. Harper has written for television as well as crafting novels, and his experience with dialogue shines in the propulsive pages of this novel. There are no wasted moments in this book, and every gun is Chekhov’s. When Everybody Knows gets adapted, they won’t need to change a thing. –MO

Janet Malcolm, Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory

FSG, January 10

Janet Malcolm—legendary journalist with a sharp eye, a penchant for the meta-narrative, and style for days—died last year at the age of 89. In Still Pictures, her posthumous memoir, Malcolm considers not only her own memories but the act of memory-making itself—very on brand, and very appealing. –ET

Kashana Cauley, The Survivalists

Soft Skull, January 10

Kashana Cauley is one of the funnier people alive today, full stop. Between working on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah and writing for the Fox comedy The Great North, somehow Cauley found the time to finish The Survivalists, a darkly comic novel set in gentrifying Brooklyn about some very contemporary questions, chiefly: “Is it worth navigating the grind of late capitalism if the world is coming to end? And with whom should we spend whatever time is left to us?” And while Cauley doesn’t necessarily have the answers, it’s going to be fun trying to figure it out. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Maria Dong, Liar, Dreamer, Thief

Grand Central, January 10

Maria Dong’s debut is both a twisty psychological thriller and a nuanced exploration of mental illness. The narrator of Liar, Dreamer, Thief is a quiet young woman grounded by her daily rituals and overwhelmed by the world around her. She’s more than curious about a coworker, and her reality begins to unravel when she realizes her coworker is just as curious about her. What is he hiding, and why does she so desperately want to know? The extremely satisfying conclusion will leave you gobsmacked. I gobbled this one up in an evening, and I highly recommend it for the cold nights ahead. –MO

Tracy Kidder, Rough Sleepers

Random House, January 10

It’s a shame that America still requires of its citizens a particular kind of moral virtuosity to grapple with the most basic problems of societal iniquity. Nonetheless, we must celebrate these prodigies of good work when we encounter them. So has Tracy Kidder done with Dr. Jim O’Connell in Rough Sleepers, the story of one man’s efforts to bring healthcare to Boston’s unhoused population, along with compassion, kindness, and humanity. I wish we didn’t need the Jim O’Connell’s of the world, but I’m glad we have them. –JD

Henry Marsh, And Finally

St. Martin’s Press, January 17

One of Lit Hub’s first viral posts was an excerpt about brain aneurysms from Dr. Henry Marsh’s Do No Harm. Marsh, one of Britain’s foremost neurosurgeons, writes about the brain in practical prose, a clarity which makes, well, brain surgery seem not too difficult to understand. In his new novel, And Finally, Marsh delivers a more personal exploration of death, life and neuroscience. Now retired, Marsh is diagnosed with advanced cancer. As someone who has spent his entire life facing the potential death of his patients, he now must contemplate what death means to him. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Dan Kois, Vintage Contemporaries

Harper, January 17

The HarperCollins Union has been on strike since November 10, 2022. Literary Hub stands in solidarity with the union. Please consider donating to the strike fund.

I find Dan Kois’ nonfiction writing reliably delightful, so I’m excited to crack open his debut novel. Set in New York City beginning in the 1990s, Vintage Contemporaries follows Em, a young Midwesterner who moved to the city to pursue a career in publishing (yes, thank you) and her new close friends—Emily and Lucy—two very different women, both equally committed to art. Em loses touch with both women as her career advances and her personal life becomes consumed by marriage and parenthood, but after Lucy’s death, she and Emily rekindle their friendship, forcing Em to examine her life through a new lens. –JG

Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein, Forbidden Notebook

Astra House, January 17

Alba de Céspedes’s classic domestic novel was first published in Italy in 1952; now, it’s being reissued with a translation by Elena Ferrante’s translator, Ann Goldstein, and a foreword from Jhumpa Lahiri, who calls Céspedes one of Italy’s most “incendiary, insightful, and overlooked writers.” The story centers around a middle-class housewife and mother in postwar Rome, who’s unable to articulate her dissatisfactions until she begins writing in a—you guessed it—forbidden notebook. Sounds like the perfect winter read to me. –Eliza Smith, Special Projects Editor

Daniel Torday, The 12th Commandment

St. Martin’s Press, January 17

Full disclosure, Daniel Torday has contributed several great essays to Lit Hub: as a writer he is erudite, provocative, and deeply humane. So I am very much looking forward to The 12th Commandment, which follows a heavily religious Judeo-Islamic sect that has journeyed from Brooklyn deep into the rural Midwest at the behest of their “prophet” Natan. Things take a dark and murderous turn, which lures visiting New York journalist Zeke Leger into an ever-thickening mystery. –JD

Italo Calvino, tr. Ann Goldstein, The Written World and the Unwritten World: Essays

Mariner Books Classics, January 17

A new collection of the brilliant Italian writer’s essays, forewords, articles and interviews—all previously untranslated and many previously uncollected—to add to the personal library of any completist. –ET

Bret Easton Ellis, The Shards

Knopf, January 17

Bret Easton Ellis is back, this time with a new serial killer novel that brings together all the best aspects of Less Than Zero and American Psycho. It’s 1981, Missing Persons is playing on the stereo, and future writer Bret is doing bumps with his prep-school friends by the poolside, dressed sharply in Ralph Lauren, as a killer makes his way closer and closer to their wealthy enclave. Ellis’ teenage emotional truths collide with violent fictional set-pieces for an epic tale of Southern Californian sins. –MO

Colm Tóibín, A Guest at the Feast

Scribner, January 17

Colm Tóibín has written more superb novels than you’ve had hot dinners (Brooklyn, The Master, The Blackwater Lightship, and Nora Webster, etc) but if you’ve only read his fiction, you’ve been missing out on a wealth of wonderful essays and criticism. In his new collection, Tóibín recalls his recent cancer diagnosis, profiles three popes, writes about a trio of authors who deal with religion in their fiction, and considers the long, tragic journey toward legal and social acceptance of homosexuality in Ireland. Not to be missed. –DS

Mario Vargas Llosa, tr. John King, The Call of the Tribe

FSG, January 17

There’s a special pleasure in a book that guides you through how a brilliant mind works, which is exactly the promise of Vargas Llosa’s “intellectual autobiography.” Here, the Nobel Prize winner surveys the readings that have shaped his political and social ideologies. Though I disagree with Vargas Llosa on many political points, I’m a great admirer of his writing, and I look forward to a thought-provoking read. –JG

Tsitsi Dangarembga, Black and Female: Essays

Graywolf, January 17

In both Nervous Conditions and This Mournable Body, Tsitsi Dangarembga used an unforgettable protagonist to explore the cost of colonialism and its intimate effects and the conflation of the personal and political. Now, the writer is exploring similar territory from a more personal angle. In Black and Female, Tsitsi Dangarembga covers her childhood cleaved from her family; the political landscape of Zimbabwe; and her road to writing. If her novels are any indication of her power as a writer, I’m eager to see what she can do with the essay form. –KY

Monica Heisey, Really Good, Actually

William Morrow, January 17

The HarperCollins Union has been on strike since November 10, 2022. Literary Hub stands in solidarity with the union. Please consider donating to the strike fund.

Monica Heisey’s comedic chops are unassailable—she’s written for Schitt’s Creek, Workin’ Moms, and Baroness von Sketch Show, among others—so I’m eager to dig into her debut novel, which tells the story of Maggie, a broke, newly divorced, languishing grad student (who is doing great!). The only thing more satisfying than a scrappy starting-over story is a scrappy starting-over story that’s really funny (actually). –JG

James Alan McPherson, On Becoming an American Writer

Nonpareil Books, January 17

For obvious reasons, James Alan McPherson is best known as a short story writer—his collection Elbow Room won a Pulitzer Prize in 1978—but this posthumous collection of his nonfiction work, edited by Anthony Walton, reveals a writer at home in any genre. From a profile of comedian Richard Pryor to accounts of his own illness, McPherson approached his subjects with equal parts wisdom and humor, and should be recognized as a great American essayist. –JD

De’Shawn Charles Winslow, Decent People

Bloomsbury, January 17

Winslow, author of the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize winning novel In West Mills, brings us back to West Mills, North Carolina in Decent People. This time, the action takes place in 1976, when three siblings are found shot to death in the still-segregated small town. The white cops are no help, but luckily Josephine Wright has just moved back home, and she’s determined to find out the truth—and a lot of other things besides. –ET

Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, Rikers: An Oral History

Random House, January 17

Rikers Island is the largest detention center in the United States… and probably its most dysfunctional. In this gripping oral history, covering the 1970s through to the present, journalists Rayman and Blau talk to all the stakeholders in Rikers’ roiling parallel society, from incarcerated people to prison officers to their intermediaries in the legal system. The picture formed from these multivocal testimonies is not a pretty one, and provides further evidence of the dire need for carceral reform in America. –JD

Iliana Regan, Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir

Agate, January 24

When lliana Regan left Chicago—where she’d earned a Michelin star as a chef—to start a restaurant and inn in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, she couldn’t have known she was embarking on a journey back to her childhood on an Indiana farm, and back further still to the stories of her great-grandmother foraging in the wilds of northern Poland. But this is what happens when you head to the woods. Equal parts naturalist, chef, and memoirist, Regan offers readers a candid account of how she found herself in the deepest parts of the northern forest, revelations of self appearing like morels after rain. –JD

Patricia Engel, The Faraway World

Avid Reader Press, January 24

Patricia Engel (Infinite Country, The Veins of the Ocean) is back this year with a powerful new story collection that captures the diasporic experience of the modern Americas in all its complexity, nuance, and humanity. Her characters move across borders and between identities, carrying with them the joys and pains of past lives, and always doing their level best to make a new go of it, whatever that may mean. Her stories also move between registers – at times sweeping and tinged with history, other times intensely personal. Always, her characters are real people, dealing with real struggles, rendered beautifully, with insight and understanding. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Editor-in-Chief

David Graeber, Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia

FSG, January 24

I still can’t get over the 2020 death of David Graeber, who is exactly the kind of aggressively elastic thinker we need to confront these omnivorously bleak times. Best described as an anarchist anthropologist, if one was forced to simplify Graeber’s worldview it’s that people make the world they live in: we make choices about justice and injustice, fairness and iniquity, and we make them together. Like… Pirates! Yes, pirates. Pirate Enlightenment is based on Graeber’s graduate study of life in Madagascar, and Malagasy history, which includes a serious strain of pirate culture, particularly among the Zana-Malata of the 18th century, who practiced a version of libertarian direct democracy. Doesn’t sound too bad, these days… –JD

Selby Wynn Schwartz, After Sappho

Liveright, January 24

I can’t wait to get my hands on this debut novel, full of what author Selby Wynn Schwartz calls “speculative biographies” of real-life women from the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Sarah Bernhardt, Virginia Woolf, Lina Poletti, Josephine Baker, Colette—the list goes on), all fighting for control over their lives. Longlisted for the Booker Prize, After Sappho is composed of vignettes and occasionally breaks into a collective chorus that feels painfully relevant for 2023: “What did we want? To begin with, we wanted what half the population had got by just being born.” –ES

Aleksandar Hemon, The World and All That It Holds

MCD, January 24

I’ve loved Aleksandar Hemon’s writing for about fifteen years now, ever since I picked up his dazzling 2008 sophomore novel The Lazarus Project. I consider his 2013 essay collection, The Book of My Lives, to be one of the most brilliant and devastating works of its kind. All that to say, the publication of a new Hemon novel is, for me, a capital E event. The World and All That It Holds (which I will finally be able to read in T-minus one month) is the story of a young Bosnian Jew who, in the wake of Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, is drafted into the army and falls in love with a fellow soldier. Together, the two men embark upon an epic, decades- and continents-spanning adventure. –DS

Sheila Liming, Hanging Out: The Radical Power of Killing Time

Melville House, January 24

More books about hanging out, less about productivity please. Sheila Liming sees the gap in our thinking about time, and the true worth in spending it in an unstructured fashion with members of our community; she believes that play is to children what “hanging out” is to adults. It’s true that the most intimate friendships I’ve built have been in settings where passing downtime together is a given, such as college dorms, summer cabins, settings where often there simply isn’t another place to be. Spending that time together, rather than alone, or on our phones, is invaluable to the true bonds of intimacy, and it’s high time we recognize it as such instead of believing there is something “more productive” we are supposed to be achieving with our one wild and precious life. –JH

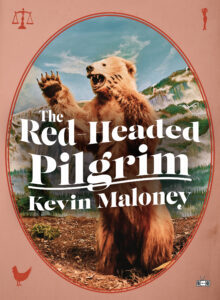

Kevin Maloney, The Red-Headed Pilgrim

Two Dollar Radio, January 24

Kevin Maloney is always good for a laugh, a wrench, and a rollercoaster ride—in his latest novel, which Chelsea Martin calls “a beautiful ode to being a fucked up pathetic virgin” (amazing) a web developer named Kevin Maloney recalls the teenage suburban psychological break/awakening that led him on a long journey to a complicated adulthood. I expect a very good trip. –ET

Martin Riker, The Guest Lecture

Grove Press/Black Cat, January 24

Martin Riker’s The Guest Lecture is like Ducks, Newburyport meets The Good Place meets The Chair, which is to say it’s an incredible book that you need to read right now. Quietly, in a hotel room with her husband and daughter sound asleep next to her, Abby is preparing for a talk she’s supposed to give the next day about John Maynard Keynes, economics, and optimism. She’s woefully unprepared. (Ah, a relatable character!) If she’s being honest, she’s also struggling to find that silver lining, that glass half-full: she was denied tenure, and America isn’t quite shaping up to be the place she wants to raise her daughter in. To rehearse for her lecture, she is using a kind of mind palace: the old trick of going through the rooms of your house and putting parts of your speech in each one. She’s also talking to the John Maynard Keynes of her imagination; he’s trying to keep her on track.

Of course, what follows is a bunch of gleeful tangents, diversions, deep dives into Abby’s past, and one Alice-in-Wonderland-inspired fever dream of a courtroom scene. There’s something so delightfully playful about this novel, about its willingness to explore the corners of the mind and to follow the firing synapses of imagination. While we fall down the rabbit hole, we are also to remember that this entire novel takes place in a single night, as Abby tries to lay still and not wake anyone. There is an intentional claustrophobia to this conceit, one that brilliantly highlights the stagnant state a lot of us find ourselves in, and there is an inherent and propulsive panic to the narrative, too, as we march towards morning. The Guest Lecture boldly asks: how can we hold hope for our tomorrow? –KY

Lydia Sandgren, tr. Agnes Broomé, Collected Works

Astra House, January 31

This is the 600-page Swedish debut novel I will be pressing into everyone’s hands this spring. Don’t be alarmed! The pages frankly fly by—in fact, I wish there were more. It’s the story of all the people left behind after one beautiful, brilliant, and enigmatic woman disappears—her husband Martin, a publisher in Gothenberg, their friend Gustav, a famous painter whose works so often feature her face, and her daughter Rakel, who may or may not have discovered a clue that might lead to her mother’s whereabouts. This is a big, compelling family drama that’s also a mystery, and also a treatise on art and artmaking and friendship and getting older, and it will suck you in and refuse to let go. –ET

Delia Cai, Central Places

Ballantine, January 31

Can you ever really go home again? Delia Cai (of Vanity Fair, also of Twitter) poses this question of her high-flier protagonist, Audrey, who fled her small hometown in Illinois long ago for the dream and promise of New York City. Now Audrey is engaged, and her fiance Ben has requested to visit the hometown she said goodbye to years ago and all that it holds: her domineering mother, quiet father, friends that have rooted and remained in Illinois, and an old crush that knew and understood her way back when. Audrey must come to terms with who and what she left behind, reacquainting herself with her family and her ideas of them, and most of all, she must re-meet a version of herself she thought she’d seen the last of, a version of herself that may be truer than who she is now. –JH