When I first met her, I did not recognize her. The truth is, I did not even care for her. It was in Elaine and Willem (Bill) De Kooning’s loft—in 1943 or 1944—on an icy New York winter’s day. I was going to the Art Students League. Bill was about forty, she and I were in our twenties, and I had just come from the first loft I had ever laid eyes on, which I then had no idea I would ever call my own.

Coming from Europe, I believed in abstraction. The Art Students League and the few galleries up and down Fifty-Seventh Street showed figuration—pensive and sad or acid and lurid, of men and women in sweatshops, in subways, and on farms, the exploited exhausted by the Depression—or modern French masters. But the first art show I ever saw in my life had been a Paul Klee exhibition in the Buchholz Gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street, where they also showed the severe, neat Cubism of Juan Gris. I was hungry for more abstraction.

Then, at a party of political refugees in a farmhouse in New Jersey near Flemington Junction that had been renovated by the German sociologist Fritz Henssler, I saw a small painting. It was green and gray and black. In it leaned a curvilinear shape like a number eight, or two sliced 0s, egg-like shapes snugly fitting. There was something still and clear about the little thing. The small abstraction was beautiful. I’d never seen anything like it. Fairfield Porter found me staring at it. “Would you like me to take you to the man who did that?” he asked. I was thrilled. To get to know the man who had painted such a picture, to go to an artist’s studio, to see more of his pictures, was wonderful.

Fairfield said we should meet the next Sunday on Twenty-First Street, where he had once shared a loft with the photographer Ellen (Pit) Auerbach. It was a grim winter morning, and harsh, cold sunlight flooded the street, pitilessly outlining the rows of factory windows as well as each pebble on the pavement. There were no pedestrians. Sundays were melancholy in Chelsea, I was to learn later. In the bright emptiness a gust of sharp wind lifted a rag, a shred of newspaper. “Just like Odessa,” said Fairfield as he walked me across the gritty sidewalk to the next block, to a loft building on Twenty-Second Street. I was impressed. He said it so lightly. He had been to legendary Russia.

When Bill de Kooning worked, he worked. He would paint without ceasing for hours and hours.We climbed up the wooden staircase, steeper than usual, to the second and top floor. Here we found a small door. We knocked. We knocked and knocked. We knocked for a long time.

When the door was finally opened, the man who stood there looked aghast at Fairfield and me. He was obviously quite disappointed. But then he caught himself and with quick, cheerful politeness asked us inside.

The strange disappointment was explained later. When Bill de Kooning worked, he worked. He would paint without ceasing for hours and hours. He would bear no interruption of any kind, would open the door to no one. Fairfield, a figurative painter but a good friend and patron, had planned to help the then poor and unrecognized Bill by bringing the critic Paul Rosenfeld to appraise his work.

Some Sundays before, Fairfield had taken the critic by the scruff of the neck and brought him downtown. Bill was in a fury of work. Fairfield and Rosenfeld knocked and knocked. Neither Bill nor Elaine would open. Nor did they suspect that a respected critic, who could do any number of things for them, was on the other side of their door. When Fairfield explained to them later what had happened, they were crushed. They promised they would be good and open the door the next time. But the next time, when Bill finally stopped work and opened the door, there was Fairfield all right, but with him there was no critic, only an art student in a red hat, me. Still, mild and good-humored, the painter quickly got over his shock and made us welcome in his studio.

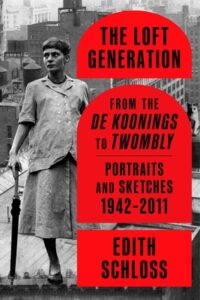

Elaine and Willem de Kooning, 1953. Photo courtesy Bridgeman Images.

Elaine and Willem de Kooning, 1953. Photo courtesy Bridgeman Images.

It was like nothing I had ever seen before. Everywhere were surfaces lashed with paint—flows and drips and spatters of paint, linear demarcations and gashes, like frontiers and ghostlike empty spaces, where a canvas had been attacked. On canvases there were waterfalls of paint and wide swaths of cancellations. On the floor, bits of drawings on cut-out tracing paper and newsprint used to mask spaces lay on gritty boards spattered with paint.

There was a large, long table loaded down with oil paint tubes, jars of enamel paint, plate glass covered with mounds of paint, coffee cans full of paint, knives, scrapers, sandpaper, rolls of masking tape, and brushes of every size and shape laid out in rows—a veritable landscape of paint and materials.

To the right, toward Twenty-Second Street, a large factory window of frosted glass muted the northern light. Bits of tape, tracing paper, and newsprint, comics and magazine cutouts were stuck to it. There were canvas racks and shelves on which stacked canvases looked in and out. Opposite this drama was an old armchair, bulging, its springs half broken, covered with yellowish-brown velours. This was where the painter sat down to stare at what he had just created.

While I am writing this, I realize that today such a setup, the large painting walls, the homemade easel, the large table flooded with materials, is perfectly ordinary in a painter’s loft. But what is a common style now was invented then by Bill and his friends to fill their new needs. At the time, it astounded me.

There was the smell of fire and brimstone in the air: here epic struggles had taken place. A man had been measuring himself against the gods with nothing but a stick covered with paint in his hand. A small man standing in front of a big, messy flatness offering itself to his truth.

When I was little, I saw a Hollywood movie about a storm at sea. The ship plunged into giant troughs, then wobbled and climbed up, only to have three-story-high waves hurl it down again. In all this foaming stood the skipper: sou’wester and slicker dripping wet, legs wide, straddling the deck, his hands on the helm mastering the bucking wheel. With every part of his body at play, the skipper was giving all he got. He was all there. He was measuring his power against another power.

So Bill would stand in front of his painting. The emptiness there was a force of nature to be overcome. The painter took it on, took on his own painting. Wide-legged, he stared at his past, his present, his enemy, his friend. There was abandon here, and joy and pain; it was daunting and it was exhilarating. How could you ever achieve anything like that?

Years later, my daughter-in-law, Yoshiko Chuma, went to visit Bill in East Hampton. She is a dancer, and I don’t know how much she understands about art. But she too was caught by that sense of Bill’s power, the same feeling that had overwhelmed me decades earlier.

“Wow,” she said. “That man, just standing there in his studio, wow!”

We were all strongly attracted to him, so small and solid, with his handsome smile and that squeaky voice that went to the heart of things.The man standing there so exposed was compact and not very tall. A shock of straight blondish hair sometimes fell over one eye and then was flicked back. He had a way of narrowing his eyes and squinching his wide, sensual lips sideways when looking hard at things, when thinking hard, and when he was embarrassed. He was courteous but would say the truth, brutal or not. Most of all, there was his voice. I can hear it right now: high, chirpy, with a Dutch accent that made it even more endearing. His “how are ye?” and his “still painting?”—which from anyone else would be taken as a put-down but from him was an encouragement—still ring in my ears.

Funny and disarming, there was a sober, working-class consideration in all he said, and he was quick and alert. He looked away, seeing things, seeing new pictures, while his singsong voice followed you. We were all strongly attracted to him, so small and solid, with his handsome smile and that squeaky voice that went to the heart of things.

There was an inner room, soothing after the thin air of the big paint-inhabited studio. It was a dark, square cubicle, like a Pompeiian dining room, and was painted in satiny purplish grays. There were touches of yellow. There were solid chairs, their backs made of two curved iron rods. The chairs, a big square table, a double bed like a big box, all stood on iron rods. They looked like the basic symbols of chairs, of a table, of a bed, they were so starkly themselves. It was a shipshape, scrubbed interior, made by Bill. It was basic and simple but glowed like a jewel box.

We all sat down around the table. Beyond this room there must have been more space, a kitchen and the usual loft factory windows and fire escape over the empty lot on Twenty-Second Street. From there, suddenly someone appeared. Had she been there all along, or had she just come in? She had bangs and wore elegant scotch plaid slacks. Without a word, she handed coffee mugs to each of us with an air so aloof I thought she was a patron of Bill’s who had just come downtown from her Park Avenue apartment to give a hand to the poor artist.

A man in an army greatcoat joined us, Milton Resnick, a follower of Bill’s, a soldier who had until recently been stationed in Iceland. He and Bill and Fairfield were all looking up at the pretty woman. She moved among them with graceful assurance. The atmosphere had changed. Who was this, speaking so brightly, who was this, so admired by all these men for the way she spoke and moved? And then it dawned on me—it was Bill’s wife, Elaine.

We must have drifted back into the studio. There were shelves with paintings stacked on them. A small one looked out; it was a Picassoid woman wrapped up and hooded with a kerchief, holding her bundled-up son. Both had big black eyes and funny snowball-like hands—unfinished areas of painting. I saw it again decades later in the Whitney Museum. It was by Arshile Gorky, a friend of Bill’s. A similar painting by Milton was near it. Gorky was much in the conversation, a loved presence. I thought his paintings were too much like Masson and Picasso, and I dared to voice this and began talking about my other preferences. But then, when I said I liked Calder, I was finally put in my place.

“All that stuff moving!” Bill exclaimed impatiently. “He makes me nerfous.”

I have never liked Calder since.

I was assistant to the assistant at Meyer Schapiro’s slide lectures at the New School, and I told Bill how Schapiro could often be inspiring. “Yes.” He nodded. “He knows everything. If after an atomic war there’ll be just Meyer Schapiro left in a cave, all will be saved. He will tell the Martians everything, he knows all they ever wanted to know about our culture.”

Later he said something no one had yet said in those early 1940s—that Marx and Freud and Einstein had led us astray.

“They want to change everything, those three wise Jews. It’s the sinuses who are destroying the world.” The sinuses? He meant the scientists.

“And there’ll be nothing left but insects,” and he described a vast landscape of burnt stone over which crept horny brown things in the lurid shine of a purple sun.

When I said something about the Mexican mural painters Harry Sternberg at the Art Students League had told us to study, he put them down.

“They think they know all about the people.” He said he knew a man, the husband of the dancer Marie Marchowsky, who had fought in the Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War and was now a successful radio executive, who thought he knew about the people. “Those guys, they think they know all about the people. When they wake up in the morning and want coffee, they holler coffee for the people, let the people have coffee!”

But painting was about the painting of paintings, not about the needs of the people. I found out later that this disillusionment with left political ideas was a strain that ran through all the conversations of the early Abstract Expressionists, who, to a man, had been starry-eyed fellow travelers until yesterday.

Even harder for me to swallow was the constant talk about the Renaissance, Rubens, the Venetians, and their brushstrokes, their brushstrokes, no one could do better brushstrokes. I was dismayed. I too had seen the Renaissance in Florence as a teenager and had been so awed by it I believed nothing could come after. But Bill’s own clear little painting I had seen in New Jersey had been a revelation to me. It was abstraction—severe, clean, shining abstraction, its own story. And now Rubens, Titian, Tintoretto. I could not understand Bill’s treachery. Those rains of bodies, those cascades of thick and bulging pink flesh, those masses of heaped-up drapery, those complicated compositions so hard to disentangle. But Bill said they were about nothing but painting, traces and traces made up by hand, which built up unending movement. And he added, “It was the burchers behind it,” and nodded his head with grim nostalgia, “nothing but the burchers.” He meant the commissioning burghers of Holland and Venice.

Of all modern artists, only Soutine came up. And though there were many canvases of Bill’s and his friends, I saw no art reproductions except one—Masaccio’s Adam and Eve.

Two figures, naked, woman and man, mouths open, were running, running from Paradise.

I sat there in shock. Bill’s untoward opinions had taken my breath away. But his paintings and stance as a painter were even more shocking. Later that week I went back to the Art Students League full of the extraordinary man downtown. I wanted to write about him in the Art Students League Bulletin, to clear it all in my head and for others as well. I had found a great painter like no one else. But Helen DeMott and Cicely Aikman, who ran the little paper, did not take my word for it, did not believe. It is a silly fact of history that they published instead an article on the Swiss surrealist Sonja Sekula, a nice person, but not such a good artist. If I had been allowed to write my tale of de Kooning, I would have been the first ever to write about him.

After that first long session in Bill and Elaine’s loft, we all went to eat at the Automat, a cafeteria on Twenty-Third Street. Elaine talked to Fairfield, Milton, and Bill, but not to me. Neither in the loft nor in the cafeteria did she acknowledge me. Who was this art student who had come instead of the all-important critic? As we all sat there munching our meat and potatoes, she suddenly looked out the plate glass window. Across the street was one of those turreted little office buildings still left over from the 1890s. High on its brick sidewall over an empty lot was a lighted window. Elaine pointed to it.

“Look! Rudy is in!” she told everyone brightly.

When I timidly asked, “And who is Rudy?” she noticed me at last. She gave me one devastating look. Not to know who Rudy was? How could I have guessed she counted him, along with Milton, Fairfield, Edwin Denby, Tom Hess, and Charlie Egan, as one of the most trusted admirers at her court. After the long, haughty stare, I was dismissed once more.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Loft Generation: From the de Koonings to Twombly: Portraits and Sketches, 1942-2011 by Edith Schloss, available via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.