In Which Jonathan Lethem Possibly Overthinks Our Interview Questions

BONUS: On the Importance of Not Writing

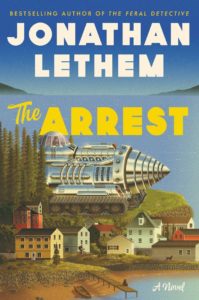

Jonathan Lethem’s The Arrest is out now from Ecco Press, so we asked him some questions about when he writes, tackling writer’s block, and what he never discusses in interviews.

*

Who do you most wish would read your book? (Your boss, your childhood bully, Michelle Obama?)

This is a good premise for a story, or maybe for a dream: what if your childhood bully turned out to be your boss, and they were also Michelle Obama? What sort of book would you write for such a person to read? Would you publish it or simply print out a single copy of the manuscript and tiptoe into their office—your bully and boss Michelle’s office that is—and leave it neatly stacked on their desk? Like Kafka’s Letter to His Father, or this; would such a communique really be meant for anyone else’s eyes?

Honestly, I write for that teenager who is just this instant making the move for the grownup’s shelves in the library, or their parents bookcase or bedside stand, trying to find out the secret. Which is not to say that I know it. But that is the secret: that we don’t know it.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I’ve been interviewed a lot. I’ve moved through phases of fascination with it—what can I do with this mode called “interview,” how can I shift it, how much can I make it mean? I think they even published a collection of interviews with me once, somewhere. I’ve probably said and everything I truly believe, and its opposite as well. Like Nimoy, I’ve lived long enough to declare both “I Am Not Spock!” and “I Am Spock!” Yet the feeling persists that I’m never precisely in the conversation I dream of. Why doesn’t anyone ever ask me about the dedications to my books? Too shy, or does no one read them? I wonder frequently about the dedications in other people’s books. In certain cases I feel that what I’ve tried (maybe failed?) to say about prisons and hospitals and schools and urban renewal and other Foucauldian devices has been glossed past, in favor of talking about comic books and pizza and the Top 40. Certainly that’s my own damn fault. Other times I grind into seriousness when I’d prefer to scream, “I meant it to be funny!” But that never works. The jokes that don’t land aren’t jokes, it turns out.

What time of day do you write?

I am writing this now at 11:54 am. Most of what happens, happens before lunch. There are a couple of books that were written before babies woke up, which is to say from 4 am to 6 am, in the dark, after making the silentest cup of coffee I could manage. Those are murky years, and I’m not sure I’ve ever recovered.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

There’s little in this business that really involves tackling, and not many things I’ve encountered in the practice were shaped like a block. Perhaps “tacking” happens, like a sailboat working against a tide or a wind. Mostly waiting, staring, training oneself to abide and endure with the uncertainty of an effort that is on the best days mostly stillness, after all. How many seconds are actually spent pressing one of these alphabetic keys downward? Is every instant where that isn’t happening a “block”? And how do you count the action of the delete key—in the positive, or the negative? It’s probably better not to think this way.

“So much guilt at this scene everywhere! Let’s absolve it. I haven’t read Proust.”

I put myself in a position to add to the given project on the most regular basis I can manage. I tell my students that’s every single day, and sometimes I’m not lying when I say that. Thanks to that habit the books have piled up, to an extent which has confronted me with the problematic word “prolific” in at least 47 percent of the interviews alluded to in the earlier question. Yet not-writing is the constant companion, the way I walk around, the essence of my being. If I allowed the not-writing to make me feel like I was a phony, or suffering a professional ailment, I’d be suffering too much.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Ordered from earliest encounters, a reckoning. (Never actually tried this before.) Albert Payson Terhune’s His Dog; Hector Malot’s Nobody’s Boy; John D. Fitzgerald’s The Great Brain at the Academy; Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles; Agatha Christie’s Curtain; Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In the Castle; George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides; Philip K. Dick’s Ubik, Valis & The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch; James Baldwin’s Another Country; Iris Murdoch’s The Black Prince, Stanislaw Lem’s Memoirs Found In a Bathtub; Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren; Anna Kavan’s Ice, Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics; Walter Tevis’s Queen’s Gambit; John Barth’s The End of the Road; Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children; Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled. Melville and Kafka too, but that gets muddled up with my teaching those texts.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, TV show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

My father’s paintings.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

The simplest, and I got it in person from Stanley Ellin. I was lucky enough to know him when I was a kid. “Keep writing.” Stan said it as though he saw I had the curse, and he’d merely ordained with a brief wave of his hand what we both regrettably understood.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass in one volume, my mother’s copy, an inexplicably beautiful 1941 Heritage Reprint Edition on wartime ration paper. I have it right here beside me as I write.

Name a classic you feel guilty about never having read?

O guilty pleasure when you connect! O guilty secrets when you haven’t yet! So much guilt at this scene everywhere! Let’s absolve it. I haven’t read Proust. (The clock is ticking.) I look forward to it.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

I find this particular counterfactual problem really stumping, because I begin to think about the implications. If I wrote it, then I wouldn’t have been able to read it, so how would I have become someone who wished they could write it? If I pick a book essential to my core identity then how, if I remove it from my formative experiences in order to later write it myself, how could I have become myself at all? I also feel sort of weird and bad taking away someone else’s experience of being themselves, and writing their own book.

Maybe I’ll just take the wonderfully crazy Mr. Dog away from Margaret Wise Brown, since I would be denying her neither the cash machine that likely paid all her descendants’ mortgages (Goodnight Moon) nor the authorship of the most beautiful book ever written (The Runaway Bunny). Thought actually I might want to be Garth Williams, the genius illustrator of Mr. Dog. Can I just be Garth Williams for the duration of his illustrating of that book? I think I have failed this question, sorry.

__________________________________

The Arrest by Jonathan Lethem is available via Ecco Press.