“In This Country, We Murder; Then We Honor.” Peter Orner on a Death in the Town His Family Loved

The Small Details Before and After a Tragedy

A decade ago, in Fall River, Massachusetts, my mother’s hometown, the water in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Pool was so murky that a woman drowned without anybody noticing. She’d gone down the water slide and hit her head. She sank and remained unseen until, two days later, her body rose to the surface. Some boys who’d climbed the fence to swim after hours, at night, discovered her floating.

I don’t tell this to humiliate Fall River. Plenty of people have already done that. The story of the woman who drowned unobserved in a crowded public pool ricocheted in the media around the world—for a day.

My grandfather Fred loved Fall River so much he didn’t tolerate anybody making fun of it. He collected books about King Philip’s War, which was fought in and around what’s now Fall River. After some pilgrims with firearms ambushed King Philip at his hiding place in Misery Swamp, they put his head on a spike and made a parade out of it. I read this in one of my grandfather’s books when I was a kid. They did the same thing to King Philip’s staunch ally, the chief of the Pocasetts, Queen Weetamoe. They chased her into the Taunton River. It’s said that Weetamoe couldn’t swim, but even if she could have, the currents in the Taunton would have been so strong she’d never have made it across. When they dredged her body up, they put her head on a spike, too.

Many things in Fall River are christened after these two. A mill, a cigar company, and a national bank, all were named for King Philip. Weetamoe got a street. My mother grew up on it. In this country, we murder; then we honor.

*

The drowning at a public pool in 2011 was the result of a grotesque confluence of facts. The lifeguards weren’t well trained. The pool was perennially underfunded. That summer, the rec director made the decision to fill the pool without first cleaning out the dirt and dead leaves and debris that had accumulated during the off-season. He was under the gun to open.

Failure after failure. The dirt, the dead leaves. Open the pool on time. It was hot, so hot. Fall River is a cauldron in summer.

Marie Joseph. The woman’s name was Marie Joseph. She was a mother of five and worked as a housekeeper.

*

In As I Lay Dying, Darl doesn’t witness his mother’s death. Pa has sent him and Jewel to town with a load of lumber. The load is worth three dollars. Three dollars is three dollars. And yet it’s Darl who gives us the minute details of her last hours. Faulkner knew that you don’t need to be present to see, that vision is as much about imagination as it is proximity. It’s Darl, who’s not there, who tells us that Addie Bundren watches out the window as Cash saws the planks for her coffin in the failing light.

The sound of the saw is steady, competent, and unhurried, stirring the dying light so that at each stroke her face seems to wake a little into an expression of listening and of waiting, as though she were counting the strokes.

The boys climbed the fence and stripped off their shirts and jeans. It must have been dark but the streetlights along Eastern Avenue would likely have enabled them to see the shape floating on the surface of the water. It wasn’t a scene out of a horror movie. It suddenly got very quiet. The boys whispered to one another. They knew the woman bobbing in the water was dead and that there was nothing they could do for her, not in this life anyway. A few moments of stillness as they stood there in their underwear at the edge of the pool. Then they got dressed and climbed back over the fence and called who needed to be called.

________________________________________

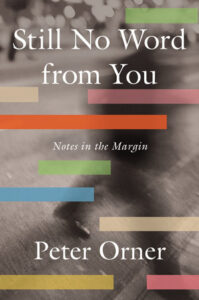

Excerpted from STILL NO WORD FROM YOU: Notes in the Margin by Peter Orner. Published with permission of Catapult. Copyright © 2022.

Peter Orner

Peter Orner is the author of the novels The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo and Love and Shame and Love and the story collections Esther Stories, Last Car Over the Sagamore Bridge, and Maggie Brown & Others. His previous collection of essays, Am I Alone Here?: Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. A three-time recipient of the Pushcart Prize, Orner’s work has appeared in The Best American Short Stories, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Granta, McSweeney’s, and has been translated into eight languages. He has been awarded the Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a two-year Lannan Foundation Literary Fellowship, the California Book Award for fiction, the Edward Lewis Wallant Award for Jewish fiction, as well as a Fulbright in Namibia. He is the director of creative writing at Dartmouth College and lives with his family in Norwich, Vermont.