Whenever a TV or film director wants to suggest refinement or stuffiness, a piece of classical music will inevitably be playing in the background of whatever gilded room or formal garden their displaced protagonist has just walked into. Usually, it’s music from the Classical or Baroque period.

For a few decades in there (the 1980s and ’90s were particularly culpable), it was, in fact, nearly always from one of two pieces: Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik or Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (generally “Spring”). When Ace Ventura, pet detective, infiltrates billionaire Ronald Camp’s black-tie soiree—or when Vicki Vale enters the museum in Tim Burton’s Batman just minutes before the Joker arrives to defile it—or when a gloating Lucy Liu bests her young chess opponent in Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle—it’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik.

As it is, also—in similar contexts—in Daddy Day Care, There’s Something about Mary, The Bonfire of the Vanities, and Up Close and Personal. To name only a few. (Because it’s not like Mozart left us over six hundred multi-movement works to choose from, most of which are way better than Eine kleine Nachtmusik.)[1]

It’s “Spring” from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, on the other hand, when Julia Roberts accompanies Richard Gere to his dinner meeting at that fancy restaurant in Pretty Woman—and when James Bond meets the villain Maximillian Zorin at a black-tie garden party in A View to a Kill—and when King Julien, seated in the first-class cabin of the penguins’ makeshift plane in Madagascar 2, kicks Melman into coach with the words, “It’s nothing personal; it’s just that we’re better than you.” (It can also be heard in the snobbiest scenes of Spy Game, The Hangover, Pets, and—since we’re at it—Up Close and Personal. Again.)

“Spring” is heard in commercials, shows, elevators—always in the most horrible, priggish contexts—to convey a snooty milieu. Whenever I hear it, I immediately break out in hives. So either the movies have truly ruined it for me or Vivaldi was better at capturing the atmosphere of spring than I give him credit for.

Possibly thanks to Google and Spotify, film music directors have begun to realize that the classical repertoire includes more than three pieces and have expanded their snob-scene playlists accordingly.[2] Some examples that spring to mind are: Kingsman 2, which uses Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings in C Major, Op. 48 for the scene when Eggsy has dinner with the Swedish royal family, and Bad Moms, which makes use of Mozart’s Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 493 for Christina Applegate’s fancy Martha Stewart–catered party.

All of these scenes, among the billions of others I have not listed, underscore the association between classical music and the stuffy, moneyed elite.

Before I explain why this is bullshit—and also why it isn’t—I should distinguish between snobs and people with money. There are, of course, plenty of rich people who aren’t snobs. Take one of my early benefactors, Paul, an amateur pianist who frequently opens his homes and bank accounts to young, up-and-coming musicians. He has a wine cellar and a membership at the University Club and a place in the Hamptons, but he still drives an absolute-piece-of-crap Volvo that’s not quite as bad as my parents’ but that still bursts into flames in the middle of I-495 sometimes when the traffic’s especially bad. And he’s been living without a tennis court, which I didn’t even know you were allowed to do in the Hamptons.

But instead of having one installed—or replacing his car with one that doesn’t double as a pizza oven—he bought a Steinway for his favorite performing arts organization when their board members (all of whom probably do have tennis courts) didn’t want to cough up the cash.

For as long as there have been snobs in the classical music scene, classical musicians have been praying for salvation from them.Conversely, there are plenty of people without money who are snobs. My roommate while I was at Juilliard was one of the biggest snobs I’ve met—even though our kitchen counter was the kind that you could peel if you were bored and the only windows in our common area doubled as the wall of our neighbors’ living room. All you had to do to bring out his inner Lucille Bluth was to eat a plate of spaghetti Bolognese in front of him—and soon he’d be lecturing you about how spaghetti is not the right kind of pasta for a ragù and how salt, in his view, is a crutch that’s needed only in the absence of true culinary virtuosity. And before long, your presence in the kitchen would no longer stand in the way of his dream of being left alone to read and analyze Finnegans Wake.

For the purposes of this chapter, though, this distinction is moot. Anyone with money will be considered a snob (rich people who aren’t snobs will forgive me because they’re cool like that) and anyone without money who still, for whatever reason, wants to be considered a snob can keep that honorary title but should know that only some of what follows applies to them.

Snobs have, in fact, always been attracted to classical music. They’ve been making themselves indispensable to the industry’s economic tapestry since the days of Bach and Mozart, when wealthy members of the nobility—kings, princes, archbishops, and what have you—employed musical geniuses the same way they employed cobblers and cooks and couturiers (many of whom were also likely geniuses). The dynamic has evolved slightly since then, but there still isn’t a large enough audience base—or enough public funding—to get rid of the snobs altogether.

This is how, in a relatively recent incident called Mahlergate,[3] a whole concert hall of them went full torches-and-pitchforks on a man whose cell phone went off in the middle of a performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.

It’s also how, a few years back at the Berlin Philharmonic, I ended up getting stuck sitting next to a woman who lost her shit every time anyone clapped between movements.[4]

(It was gross. She kept trying to impress her date by screaming, “No! You’re not supposed to clap yet!” at a bunch of people who couldn’t hear her.)

Here’s what was funny about it:

1. The people who were clapping between movements were politely expressing their enthusiasm for the music. Their applause didn’t bother anyone in the hall apart from this woman. This woman’s impolite expressions of frustration and snobbery, on the other hand, bothered quite a few of the people sitting around her.

2. In going nuts about something that doesn’t even bother most performers, she revealed that she was probably far less expert than she was trying to make herself out to be.

3. Imagine having such a fragile equilibrium that this is the sort of thing that unhinges you.

By the way, in case any of this is making you nervous about attending a live performance, don’t worry. There’s a whole section on concert etiquette in chapter 12 of my book and much of it focuses on when to clap. It also covers when to be a dick about other people not knowing when to clap. (Never. You should never be a dick about it.)

*

The fact that there are snobs who listen to classical music does not mean, however, that classical music is for snobs. To say that it is is to say that gold and princesses are for ogres—or that all the chocolate that comes into my house is for me. Just because someone likes a thing—and happens to be holding that thing hostage—does not mean that that thing is for that someone.

In fact, for as long as there have been snobs in the classical music scene, classical musicians have been praying for salvation from them.

Mozart’s hatred of his employer the Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo was well documented in those letters to his father that did not center around descriptions of his gastrointestinal activity; he often complains, in them, of how poorly he’s treated by the archbishop—and of the archbishop’s stinginess—and in one he even writes that he “hate[s] the archbishop to insanity.” It’s likely that Bach felt similarly about his patron Duke Wilhelm Ernst of Saxe-Weimar, who once imprisoned him for a period of four weeks for the crime of trying to resign.

But musicians often have to swallow their pride and work for people they hate. They need food just like anybody else, and musical instruments require shelter from the elements. I’m lucky to be able to say that the vast majority of my professional contacts have been people I like. But I’ve still done my fair share of pride-swallowing and ass-kissing. Unfortunately, the story I’d really like to tell you—about this absolute nightmare of a woman—is off-limits.[5]

But I can tell you that I’ve dealt with plenty of rude and ignorant remarks made by influential patrons—and inappropriate comments and advances made by industry kingmakers and competition judges—and that in most of these instances I’ve had to be polite and charming—and seemingly grateful (even in my refusals)—so as to avoid losing work and making powerful enemies.

I can also tell you that I once had to eat an entirely raw, uncured jumbo shrimp—even though it was gray and so, so rubbery and I’m terrified of germs and bacteria—because it was served to me, after a concert, at the palace-like home of two well-known musical benefactors and I was scared of what would happen if I offended them (or their private chef). Not really the same as getting thrown in jail for trying to quit my job, but traumatizing nonetheless.

The good news is that some of the snobs have started dying off, so there are fewer of them now. This hasn’t been overly wonderful for musicians from a financial standpoint, but it has forced the industry to adapt in the hopes of attracting new audiences. (I’m oversimplifying. Survival is only part of the impetus behind the changing industry. Many musicians have grown tired of the stagnant air surrounding this music and have reached, accordingly, into their stores of creativity for their own artistic growth and sanity.)

As a result, the classical scene has blossomed into a world of innovation and experimentation and very trim waistlines. There are young, vibrant, beautiful performers like Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Elena Urioste, Karim Sulayman, J’Nai Bridges, and Yuja Wang—as well as ensembles like Quatuor Ébène and the hilarious Igudesman & Joo—who are sweeping through the industry like Marie Kondo through a walk-in closet, rolling socks and sparking joy with such dedication that many of the surviving snobs have been converted.[6]

(If you’re a snob looking to be converted, just google “J’Nai Bridges, basketball”—or take a look at Karim Sulayman’s I Trust You—or listen to Quatuor Ébène’s “Someday My Prince Will Come.” If those don’t work, then the unapologetic silliness of Igudesman & Joo’s A Little Nightmare Music—or the disarming artlessness and extraordinary musicianship of Elena Urioste and Tom Poster’s #UrePosteJukebox Instagram videos—certainly will. Snobs can, actually, change. I was a snob back in the day. Or I thought I was, at least. As it turns out, I was just unhappy.)

Here’s a story. When I was at Juilliard, I took part in the Gluck Community Service Fellowship Program, which sent students around New York City to play in various facilities—like prisons, schools, and nursing homes.[7] Once, my duo partner, Izia, and I were sent to perform in the psychiatric ward of a hospital.

Don’t let the snobs push you out. While the classical industry may have been designed with snobs in mind, classical music was not.Going into the experience, I tried my best to embody the kind of calm, enlightened, politically correct attitude that my mother would expect from someone she had raised. But secretly I was terrified. My only associations with psychiatric institutions were the horror movies I’d seen, and at one point, when I turned around to see a wide-eyed face staring at me through the round window in our green room, I almost screamed.

Moments later, though, I was greeted by one of the most receptive audiences I’d ever encountered—an audience full of attentiveness and devoid of any pretense or formality. There was a man who requested the “theme song from Platoon,” which Izia knew as Barber’s Adagio for Strings, and as we did our best to reproduce the piece from memory, he sobbed openly in gratitude. There was a woman who was fascinated by our synchronization, challenging us to repeat the beginning of our Mozart duet with our eyes closed and cheering us on throughout the experiment. And there was another woman, with a short pixie cut, who got up and waltzed whenever we played a piece in 3/4 time.

These people were not snobs. Some of them weren’t even wearing pants. And yet they connected with the music in a way that I have seen few snobs do—and none while sober.

The point is, don’t let the snobs push you out. While the classical industry may have been designed with snobs in mind, classical music was not. Many former snobs are, like me, converted and ready to welcome you with open arms. And the ones who aren’t—the ones who just want things to go back to the way they were when people enjoyed getting cell-phone-ring-shamed in front of thousands—don’t deserve the beauty these composers gave us—or the thrilling creativity and innovation that my favorite artists are serving up now. It was meant for you.

Yes, YOU.

I’ll leave you with one final thought:

Mozart once wrote a piece entitled “Leck mich im Arsch.” Which translates, roughly, as “Lick Me in the Ass.” Not exactly country club music.

***

[1] He did.

[2] Movies made before the year 1980 also used a wide range of classical pieces (often, even, without mention/implication of snobbery). I can’t speak to why this variety went missing for two whole decades, but it’s probably linked to whatever aesthetic plague beset the areas of fashion, grooming, car design, and architecture during that same time period.

[3] By the two people who called it that.

[4] In this case, movements, as we will cover later, are segments of a piece.

[5] The short of it is that the nightmare-witch hated me—and I hated her, but I had to pretend that I didn’t—and now she’s dead. (I didn’t kill her, though. She was just really, really old.)

[6] I should mention that Yo-Yo Ma has been a proponent of innovation for decades, collaborating with artists like Bobby McFerrin, Rosa Passos, and Lil Buck; while Sir James Galway, another classical legend, has built his popularity around approachable programming, humor, and his wonderful Irishness. But as Sir James Galway and Yo-Yo Ma, they are practically industries unto themselves, which separates them, at least insofar as audiences are concerned, from the rest of us.

[7] This makes me sound very noble and generous, but I actually got paid to be charitable, and I spent all the money on shoes. So nobody should feel compelled to nominate me for sainthood.

__________________________________

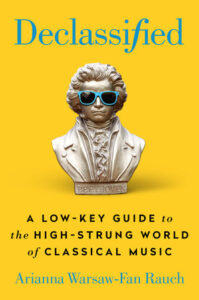

Excerpted from Declassified: A Low-Key Guide to the High-String World of Classical Music by Arianna Warsaw-Fan Rauch. Excerpted with the permission of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Copyright © 2022 by Arianna Warsaw-Fan Rauch.