Except for what happened with little George Meeker, my first year in the classroom went rather smoothly. In fact, I think it’s fair to say I had more trouble outside the classroom than in it. I had students who didn’t care and who wanted to fail, so of course I failed them. I got through mostly though without having to do that too often. I’d call parents and talk to them, I’d arrange conferences with them, and generally take the time that the job required to keep everybody on track.

I wouldn’t vouch for how much anybody learned about writing. They learned one hell of a lot about the world, eventually, but you can’t really teach writing by talking about it, any more than you can teach somebody how to ride a bike that way. You’ve got to put a person on a bike and run alongside of him until he gets the idea, and if you want to teach writing you have to make your students write. So I had them writing every day. As I’d promised, they each had to keep a daily journal. I also had them writing book reports, business letters, and personal narratives about what happened to them over the summer, or about what they wanted to do over the holidays, or during spring break. I had them write about abortion, and gun control, and civil rights, and capital punishment. I had them describing what Rocky Road ice cream tastes like; or a raw potato; or pasta with meat sauce. Describe, analyze, compare and contrast, define. . . write, write, write. I also told them that I would not read any page that was folded over in their journals. It was not a promise, so I didn’t think I would feel too bad if I did what Mrs. Creighton demanded of me.

In any case, I soon realized it was impossible to read every page of the journals with so many students. So I learned to just briefly skim through, speed reading the pages without really concentrating on much of anything. Every now and then I’d write in the margin, “Thank you for sharing.” Or, “This is good,” or, “Well done,” or “It’s good to be honest.” Stuff I almost never had to explain, and could be applied next to almost any text. Sometimes I didn’t read the journals at all; I was so pressed for time I only paged through and wrote my equivocal marginal notes without reading a word. Even doing that took hours. (Remember, I had 120 to 130 journals to read each week.) There were very few folded pages and those I did read, I saw nothing in them that warranted either being folded over or my interest. At least in the beginning.

But I had them writing at least. The problem was, of course, you can’t really learn much about writing unless you have a pretty good editor—and I mean both line by line, and overall—and there was no way any human being, even Superman, could keep up with so much writing from so many people over so short a time. I don’t want to keep harping on it, but you must understand: to teach writing you have to respond to their writing. What do you do with them while you’re taking the time to respond to what they’ve written? You get them to write something else. But this does something pretty fatal to your energy and your willingness to plug away on the work they’ve already turned in, because you know as soon as you’re done with it, they will have something else to turn in, and while you’re working on that, what do you have them do? Write something else, and it goes on and on like that until, I suppose, a teacher finally burns out. I don’t know how long it would have taken me. After two years, I was okay, but who knows? I’ve heard that when a teacher burns out it really is like going down in flames. Talk about the rock up the hill. Compared to an ordinary high school English teacher, Sisyphus had it made.

Still, I got into it sometimes. The problem wasn’t always daunting if you got students who were smart and fun to work with. I had students I really treasured. It’s only natural, of course. You are drawn to talent because you see results fairly quickly and you feel good about that. You feel as though you’re accomplishing something. Also I had students I felt sorry for. George Meeker was one of those. He suffered at the hands of his classmates and of his parents, who gave every indication of a terrible lack of civility and grace. What happened with him is as good an indication as any of what I came to see as my duty, and it was this idea of what my duty was that got me in all the trouble.

Forgive me. I don’t want to be glib about this. When the thing that ultimately ruins you has begun, you don’t necessarily recognize it at the outset. In fact, you might not notice it at all. The truth is: Nothing on earth, ruinous or otherwise, announces itself the way we’d like it to. Until the last few weeks of my last year, I think you could say my work was at least satisfactory. For some students it was probably outstanding. Perhaps most of the others would easily forget my name and everything we did in our classes. I don’t think that’s true, but I don’t know.

One of the most important people I came to know in those two years was Francis Bible. I met him before I’d taught my first class. He was the oldest teacher at Glenn Acres School, white-haired, tall and craggy, and he insisted on being called “Professor Bible.” In a way— in a very good way—he turned out to be a sort of mentor to me. When I first saw him, at the faculty meeting that afternoon the day I was hired, I thought he was Mrs. Creighton’s father. He walked up to her and put his hands on both sides of her face and kissed her on the forehead. (She was embarrassed a little I think, because I witnessed it.) Then he turned to me and smiled. “Who is this young man?” He leaned toward me, his great mane of white hair so imposing that I took a step back. He wore a white suit, a thin black tie. His face was broad and round, with jaws that looked puffy and red. His glasses, wire- rimmed and thick, inflated his eyes, and his heavy white brows crowded around the lenses like ornamental weeds. He was tall and paunchy, with bulky shoulders and arms that bulged under his tight-fitting white suit jacket.

“This is our new English teacher,” Mrs. Creighton said. Then she nodded at Bible and told me who he was.

I shook his hand, told him I was happy to meet him. I said it was a very interesting last name.

“It just means book,” he said. “You’ve certainly met folks named Bookman, Booker, and so on. Yes?”

“I guess so,” I said.

“It’s Greek. Bible.” He still held onto my hand. “I’m not from Greece.”

I looked down at my hand and he let go of it. “I teach social studies and history here,” he said.

I nodded approval.

“And a little bit of life,” he whispered. “Yes sir.”

“Engaging,” he said loudly. His voice boomed in the hallway where we were standing. Mrs. Creighton frowned at him as he turned to her. “An engaging young man; I wonder if he smokes.”

Mrs. Creighton’s frown only deepened. She did not approve, but she was not really frustrated with him. It was clear that she revered him in a way; that she was only waiting for him to quiet and settle down so she could get started with the meeting.

Bible turned to me. “Do you smoke, lad?” “Sometimes.”

“If I ask you for a cigarette then certainly give me one.” “I will, if I have one.”

“Let’s hope you do. I’ll teach you things if you take care of me.” He turned back to Mrs. Creighton and said, “Let’s get on with our meeting, Julia.”

__________________________________

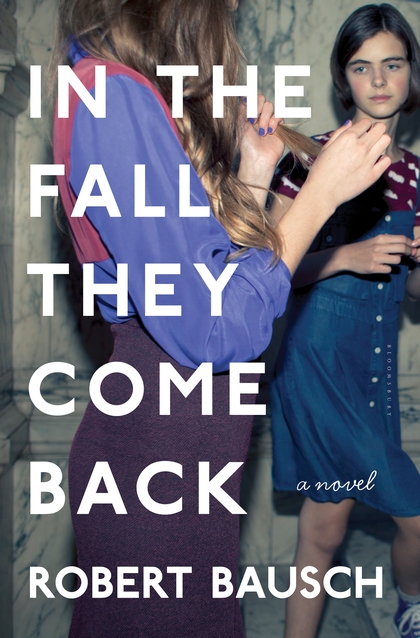

From In the Fall They Come Back. Used with permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2017 by Robert Bausch.