Translated by Jennie Erikson.

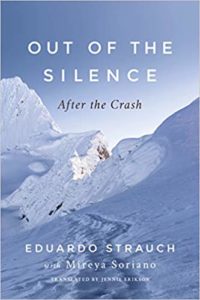

Each moment was different from the one before, but each had its own unique threat, its own unmistakable sign that something serious was happening. The plane was still moving, so I knew it hadn’t yet crashed against one of those peaks that had come into view much too close to the little window I had been resting my head against only seconds earlier. The dark mountain faces, partially covered in snow, which rose up and vanished rapidly behind the clouds, had in a single heartbeat eradicated my sleepiness as the furious turbulence threw us about in air pockets, each one deeper than the last.

The first silence arrived together with stillness after the shaking that had been tossing us about violently during that brief yet eternal time when I awaited death, eyes closed, huddled in my seat, listening to the deep roar of the engines and their final, desperate screeching. There was a strong impact, followed by other terrifying and incomprehensible noises, and suddenly I smelled gasoline and felt frigid air whipping against my face.

But the first silence was not the silence of death, although at first I thought it was and felt amazement that consciousness still existed, even without life. I opened my eyes. I had been saved. I wouldn’t be causing my parents that grief that I had feared so much in those moments that I believed were my last. It was not the silence of death, but death had come much too close and was still hovering right there; and I, caught awkwardly in my seat, facing backward, could see the face of a woman fatally wounded, lying on the floor a short distance away.

“Adolfo, what happened?” I cried out, even though I couldn’t see him.

“We fucking crashed in the cordillera,” answered the voice of my cousin from far away.

It wasn’t hard to realize the truth of this just by looking around, but it seemed necessary for someone to

say it out loud, as if the words themselves would clarify the shocking reality nearly impossible to believe: we had crashed into the cordillera of the Andes, the same cordillera that most of us had been admiring a short time before from the air as a stunning and majestic landscape. But that view, as distant and unreachable as any scenic panorama, had suddenly become the surface on which we now rested: the surface of those stiff and desolate peaks, where nothing existed but snow and rock.

I called out at once to my other cousins and to my friend Marcelo. Everyone answered me except my cousin Daniel Shaw, and that small silence in itself gave me a response that I wasn’t ready to process.

I moved with great difficulty but finally managed to free myself. I took a few steps through the fuselage, now transformed into a cave of twisted metal filled mostly with a dense jumble of seats and scattered with bloody limbs and crumpled bodies.

The first silence, ghostly and profound, was nevertheless brief because little by little, faint moans were beginning to arise like the opening notes of a terrible symphony, one made up of screams and cries of pain.

He was, like me, almost completely unharmed, and from the first moment, he took it upon himself to organize the work of freeing those who were still trapped and dragging the dead bodies out of the plane.

I headed toward the back of the plane, avoiding all kinds of objects strewn about as if there had been an explosion. The floor was bent, and the battered fuselage ended abruptly in a jagged opening leading to the inhospitable exterior. I reached the edge, and my aimless steps took me outside, where I sank into the snow. Someone grabbed me by the arm. “Eduardo, where are you going?” I turned around and went back into the fuselage. Some people were finding extra clothes to protect themselves from the cold. I found a pair of jeans and put them on over the ones I was wearing.

Out in the distance, on the white expanse that surrounded us, we saw a boy struggling on the slopes above us. We recognized Carlos Valeta, and we called out to him like he was a friend lagging behind on a simple outing and not somebody who had literally fallen out of an airplane in midflight, which is exactly what had happened to all those sitting in the seats at the back. All of a sudden he disappeared from sight. His friend Carlos Páez, whom we called Carlitos, tried to go and help him, but he couldn’t move through the snow. It was so soft that he sank into it nearly up to his waist.

The air was thin. It was hard to breathe and I couldn’t think clearly. I gradually started to notice that something was wrong with my right leg, as it was burning with pain, but I didn’t bother to examine it. I struggled to walk and my steps were erratic.

I wandered around a bit dazed, while some of the others already seemed somewhat organized with tasks intended to slightly diminish the chaos.

Most of the forty-five people on the plane were my friends or acquaintances, because the flight had been chartered in Montevideo to bring a Uruguayan school rugby team to Chile, a team of which most of us were either members or followers.

The captain of the rugby team, Marcelo Pérez del Castillo, had been my friend since childhood, from the age of seven. We had shared many experiences and wonderful times together, including studying architecture together in school and even working in an architecture studio together before the crash. We had never suspected that at the age of 25, we would go through such a traumatic event as the one we were now living. He was, like me, almost completely unharmed, and from the first moment, he took it upon himself to organize the work of freeing those who were still trapped and dragging the dead bodies out of the plane.

Two of our friends who were studying medicine in school immediately set about attending to the wounded. I approached those busy groups and tried to help them, dazed as I was.

I was able to join in the tasks that were set up by the others, but I couldn’t quite manage to take the initiative on anything. I could lend my arms and what little strength I possessed, but it was difficult for me to think clearly.

Every endeavor was absolutely exhausting. The pieces of the wreckage were tangled up in an impenetrable heap, and it took great effort to separate them. As we were freeing the bodies from this mess, we were silently sorting them based on their condition or on the gravity of their injuries. Those who had fractures or severe contusions were carried out to the snow, and we dragged the dead outside using some plastic straps that we found in the baggage compartment.

It became clear that the plane had lost its wings and that the fuselage had been severed into two pieces, losing the rear part somewhere along the mountain. What remained of the damaged plane must have slid hundreds of yards downhill on the slope, and the tremendous friction against the ground, along with the brutal impact of the plane’s abrupt stop against a small mountain of snow, had made all the seats break loose, propelling them forward violently against the front partition wall of the cabin.

I accidentally stepped on a very badly injured woman, who screamed in her delirium that I was trying to kill her.

I was so terribly thirsty that I tried to alleviate it by bringing a handful of filthy snow that was saturated in gasoline up to my mouth, as it was impossible to find an area of clean snow nearby.

The wild thirst exacerbated my deep sense of unease, and this was more torturous than the cold, which I wouldn’t have even noticed if it weren’t for the constant shivering of my body.

In a moment of rest, I looked around me at all that distant and clear space, and, strangely, I couldn’t help but admire its beauty, despite the situation.

The remains of the fuselage had ended up on the eastern slope of an enormous snow-covered mountain, and two other peaks surrounded us to the north and the south. Only toward the east could we see in the distance a long and narrow valley that wound through the mountains.

We thought that rescue would come in a matter of hours, but at the same time we figured that because of how late in the afternoon it was, we might have to spend the night in the cordillera. At 6:00 p.m. Marcelo told us to stop all our tasks and carry the wounded back inside what was left of the airplane.

Despite all the work we had done, the area we had managed to clear inside the fuselage was not enough. We predicted that the temperature would drop in the night to 20 degrees below zero, so Marcelo, with the help of others, started to build a precarious wall using the suitcases, metal fragments, and broken seats to at least partially close up the back part of the fuselage, the gaping hole that had been left when the tail broke off.

We settled in as best we could in that makeshift shelter. We barely fit inside and were piled on top of each other in a tiny, cramped space that we shared with several corpses, which we hadn’t had time to remove.

When I stopped the activity that had kept me distracted, the pain in my leg seemed to get worse. But in the midst of so many seriously wounded people fighting for their lives, my injury seemed insignificant, so I just ignored it.

The moaning was not letting up, and the cold was reaching a level of intensity previously unimaginable, even to me, who had some experience in mountains, first during a student retreat in Bariloche, though in

summertime, and then on a trip to the Alps, where we stayed in hostels. Because of the position I was forced into among that heap of tangled bodies, I accidentally stepped on a very badly injured woman, who screamed in her delirium that I was trying to kill her.

The little windows of the fuselage let in a faint glow of light, but inside it was pure darkness. I closed my eyes. The sounds of fear and of pain and the cries and moans of the dying were magnified in the shadows, and after a while in that choir, at first disorganized and confused, I could discern a certain pattern. Within that strong and continuous clamor, there was a rhythm in which groans and cries were repeated at somewhat predictable intervals. As time passed I could recognize each voice, although I couldn’t tell who it belonged to.

Then in my drowsiness and weariness, I started assigning a different face to each moan, perhaps one entirely imagined that I had never seen in the airplane or anywhere else. It was the voice of pain, of human suffering, that in some moments I imagined in the form of some ghostly creature, or without any form at all, just a deep or acute sound, a death rattle trembling in the blackness. Each groan had its pattern, its own way of repeating itself, and I, with a morbid expectation, waited for it to sound again in that sinister concert, as if it was a necessary piece of the harmonic whole.

So when a groan or cry that had been recurrent abandoned the choir of suffering, I felt an inexplicable need to hear it again, wanting that pattern, which had been broken, to be restored.

Sometimes a new voice would call out, a voice asking for someone to rub his ice-cold feet, or a voice calling out for his mother, or one begging for someone to help him because he felt like he was freezing to death. But many of the most insistent voices were gradually losing their strength, or simply stopping altogether. So when a groan or cry that had been recurrent abandoned the choir of suffering, I felt an inexplicable need to hear it again, wanting that pattern, which had been broken, to be restored. I waited with bated breath for its return, secretly needing it as a small piece of stability and order in the Dantean scene in which we were living. And when it became clear that one of those moaning voices had been finally extinguished through the hand of sleep or death, I was able to detect that silence, like a small change in the endless chorus, and I grieved the loss of it. I don’t know if it was because I was in an altered state of consciousness from the shock or because I sensed that that voice had been silenced forever.

Despite the pain that surrounded me, I felt fortunate in the midst of so much suffering. I was almost completely unhurt and so were two of my cousins and my friend Marcelo. I thought we would all be sleeping in our own beds by the next night. That first night that we spent on the mountain with no water, with only the smallest amount of food, taking refuge among dead bodies in the remains of a shattered airplane—I imagined I would remember it for years to come as the worst night of my life, a horrifying experience that we had nevertheless been able to overcome.

But then the next day rescue did not come, and there was a second night, then a third and a fourth. Things weren’t going as we had expected, and I began to fear that they were only going to get worse. Then I remembered God. I hadn’t prayed, not even during the crash.

My God, let them find us. Let rescue come. Let us be saved.

But rescue still didn’t come; not the next day, the day after, or the day after that.

God was not answering me. What did it mean?

A decade earlier, when I was 15 years old, I had gone with a group from school on a spiritual retreat in the mountains. Things were so naively clear to me then. This is what I would have believed then: that He was delaying His response; that if He was keeping quiet, it was because He was holding something better aside for me; that my human limitation was preventing me from seeing what was right; that the pain, the suffering, and even death itself were just illusions.

But in the intervening years my beliefs had been changing and, up there in the cordillera, growing weaker with each day that passed, seeing my friends dying, sinking into greater uncertainty as the days went by, I was not certain that God even existed.

My God. Let them find us. Let rescue come. Let us be saved.

At 15, not having any answer, I would have repeated the words that Jesus said, moments before dying on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” But I couldn’t even say those words anymore, because perhaps I hadn’t even been forsaken. Perhaps God wasn’t answering me simply because He did not exist.

In the evenings we prayed the rosary, and that brought me closer to my friends. The repetition of that mantra helped me feel that we were one cohesive group, but I had no other feeling of transcendence beyond that. I suppose each one of us repeated the prayers with someone on our minds. But there was no Virgin Mary present in my mind, no Jesus, and no holy saint, not even my guardian angel. I had my friends, but my spirit was very alone in the cordillera, and it was soaring over the peaks, exploring the infinite blue sky.

The silence outside, with its overpowering majesty, had changed the way we spoke among ourselves. Already we were speaking with softer voices, and with less frequency. Communication between us had been stripped of every triviality, becoming at once simpler and more powerful. The environment was forcing us to be economical in everything, to conserve every strength and eliminate every word that wasn’t absolutely necessary.

Within this quiet, important decisions, which would later contribute to saving us, were incubating. In the cordillera I saw clearly things that are so difficult to perceive in civilization and in our daily lives. The silence of the mountain instilled in me the possibility of inner silence, and it was in that silencing of my thoughts that I found a lasting peace capable of expanding all the abilities and gifts that humans possess.

_____________________________________________________

Excerpted from Out of the Silence: After the Crash by Eduardo Strauch with Mireaya Soriano, translated by Jennie Erikson. © 2019 Published by Amazon Crossing, June 11, 2019. All Rights Reserved.

Eduardo Strauch and Mireya Soriano

Eduardo Strauch Urioste was born in 1947 in Montevideo, Uruguay. In 1968 he opened an architectural studio with his best friend from childhood, Marcelo Pérez. He has worked as an architect and painter, and for many years he has lectured about his experience surviving seventy-two days in the Andes after the legendary 1972 plane crash on the Chilean-Argentine border. He is married to Laura Braga; they have five children and live in Montevideo.

Mireya Soriano is an award-winning Argentinean-Uruguayan writer. She is the author of The Rose of Tales, There Is No Time for More, Let the Sea Cry, and The Sky of the Owl.