In Praise of the Simple Beauties of Marcel the Shell with Shoes On

Olivia Rutigliano on the New Movie About the Internet's Favorite Anthropomorphic Mollusk

This week, I saw a dear old friend at the movies and I am pleased to say that he seems better than ever.

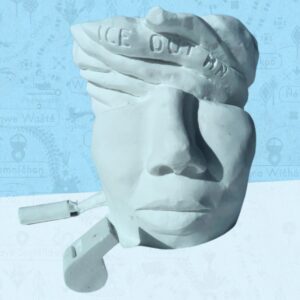

I first became acquainted with the character known as “Marcel the Shell” in my college dorm room nearly a decade ago. My sister had sent me a link to a popular YouTube video, a short stop-motion film in which a tiny seashell with a googly eye and a pair of pink plastic sneakers takes a cameraman around the house where he resides—a giant house, a human’s house—and explains how he lives his miniature life.

He exists inventively, resourcefully. He scrounges for things that he might turn into tools and gadgets and furniture. “Guess what I use as a beanbag chair?” he asks the filmmaker capturing him. “A raisin.” He uses stray hairs as string, pretends a ball of lint is his pet dog. Most of the film is like this: a little vérité-style preview into this charming lifestyle which is a dilated, cobbled-together version of our own.

Crucially, this short—entitled Marcel the Shell with Shoes On and made by Dean Fleisher-Camp and Jenny Slate—is not about a little world as much as it is about a little life. The immense charms of Marcel’s handmade (shellmade?) surroundings are surpassed by the palpable spunk of its resident. Marcel is curious, sentimental, indefatigable, and a little bit sassy. He informs the camera, “Some people say my head is too big for my body… and I say… ‘compared to what?'”

Marcel is able to produce beauty in his world by seeing everyday objects in a different way, and so too does the film.

The original Marcel the Shell short, posted to YouTube in 2010, became a phenomenon. The lore is that Slate and Fleisher-Camp had created him accidentally—she produced the funny voice, and he built a model to match. Indeed, Slate speaks about the character not as something she and Fleisher-Camp created, but as a whole identity who was inside both of them and managed to manifest from them, like Athena climbing out fully grown from Zeus’s head or Aphrodite emerging as her adult self from, well, a shell. Marcel is his own person, a fully coherent individual, even to his creators.

In real life, Marcel drew crowds and fans for his cuteness but held onto them because of his unique perspective. The popularity of the initial short video generated several sequels and two children’s books. And now, 12 years later, he has finally made his feature film debut.

Directed by Dean-Fleisher Camp, co-written by Jenny Slate and Nick Paley, and produced by A24, this feature version, also entitled Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, revisits the last few years of Marcel content while also reworking it. The story is about Dean, a filmmaker, who finds a tiny sentient shell living in the Los Angeles Airbnb he’s staying in, and gets the idea to film his daily routine. Marcel lives with his loving grandmother, Nana Connie (Isabella Rosselini), and they spend their days gardening, talking, watching 60 Minutes on Sundays, and rigging contraptions to get basic things done. “It’s pretty much common knowledge that it takes at least 20 shells to have a community,” Marcel informs Dean. But it’s just him and Nana Connie in the house—the rest of their giant group has vanished (probably accidentally packed in a suitcase and taken away by the last couple to stay there).

What results is a tender 89-minute film about the bonds that fortify our lives, from new friendships to intergenerational care.

In the film, the shorts that Dean has posted to YouTube make Marcel a kind of celebrity, and he decides to try to use his newfound notoriety to find his missing family. But his attentions are split between the longing to find his community and the desire to care for the one he already has: Nana Connie seems to be experiencing a kind of dementia, and Marcel, ever-loving, wants to use all his energy caring for her and keeping her safe. The life they live together is special and beautiful, and he doesn’t want to miss a minute of that.

What results is a tender 89-minute film about the bonds that fortify our lives, from new friendships to intergenerational care. Marcel wonders a lot about the different ways we connect to people; the discovery of the internet has him negotiating the difference between a community and an audience. Narratively, it is about what it means to build a life with someone, but it’s peppered with questions like these.

And thematically, of course, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On cannot help but be about our relationships to objects, too. So much of the film is about Marcel’s material life and his practical mindset: how he uses objects to make his life easier (for example, he climbs inside a tennis ball and uses it to traverse the house).

But it is also about how Marcel’s inch-tall perspective opens up the potential of objects and materials—not just pragmatically but aesthetically. Marcel is able to produce beauty in his world by seeing everyday objects in a different way, and so too does the film. Some of the most beautiful moments are simple, silent camera shots over the tiny treehouses built in the Airbnb’s planters, or a pattern (made with arugula leaves, flower buds, and green peas) Marcel arranges into the dirt in a window box outside. And then there is Marcel himself, this little anthropomorphic mollusk (I guess?) with his own special kind of wisdom, reminding us the ways in which even things around us are all creatures, great and small.

I find myself, after this particularly trying week in America, grateful to be seeing Marcel again.

One of the film’s many, many motifs is a reminder to pause and notice the beauty of the world around us—to live slowly and receptively, to stop and realize that we are all, in our ways, so small, and to remember the ways our lives can still make big impacts. But more than this, the film is clear that we are all (in a way) objects, all instruments. We are vehicles for beauty and love, if we only open ourselves up and let them flow through us.

This might seem trite, but if it does, that is my fault. I find myself, after this particularly trying week in America, grateful to be seeing Marcel again, shining in all his sincere glory from inside the most profound iteration of his chronicle yet. I am desperate to impart the splendidness and the earnestness of this achievement, committed to illuminating others to the wonders of this movie, candid about his ever-present perch in my heart but adamant that this film will appeal even to those who have never seen him before.

The film is genuine, never-cloying, always poignant. Nearly every shot is suffused with soft, golden sunshine and an ever so hazy, dreamlike grain. It is a warm, delicate, perfect project—a beautiful revisitation of and tribute to a character so surprisingly special and plucky that his relevance has outlasted a decade of changing popular cultural norms. Through everything, no matter what else there is, we are reminded that there is Marcel, there is Marcel, and there will always be Marcel.

Olivia Rutigliano

Olivia Rutigliano is an Editor at Lit Hub and CrimeReads. Her other work appears in Vanity Fair, Vulture, Lapham's Quarterly, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Public Books, The Baffler, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Politics/Letters, The Toast, Truly Adventurous, and elsewhere. She has a PhD from the departments of English/comparative literature and theatre at Columbia University, where she was the Marion E. Ponsford fellow. She hosts the podcasst "Culture Schlock" at Lit Hub Radio. She is on instagram at @oldebean, twitter at @oldrutigliano, and bluesky at @oliviarutigliano.bsky.social.