Rumi Hara (The Peanutbutter Sisters and Other American Stories, Nori) and Rina Ayuyang (Blame This on the Boogie) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a spring event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The two spoke about Hara’s new graphic novel, The Peanutbutter Sisters, a collection of surreal Americana stories touching on Noh theatre, intergalactic car races, and pollution.

The conversation touched on topics of culture and the individual, the art of scintillating dialogue, giving oneself permission to carry out fantastical ideas, and more.

*

Rina Ayuyang: I wanted to learn more about the Peanutbutter sisters. They feel like these superhero characters—there’s just something about them that’s dynamic, inspiring, and empowering. What was the origin of those three sisters?

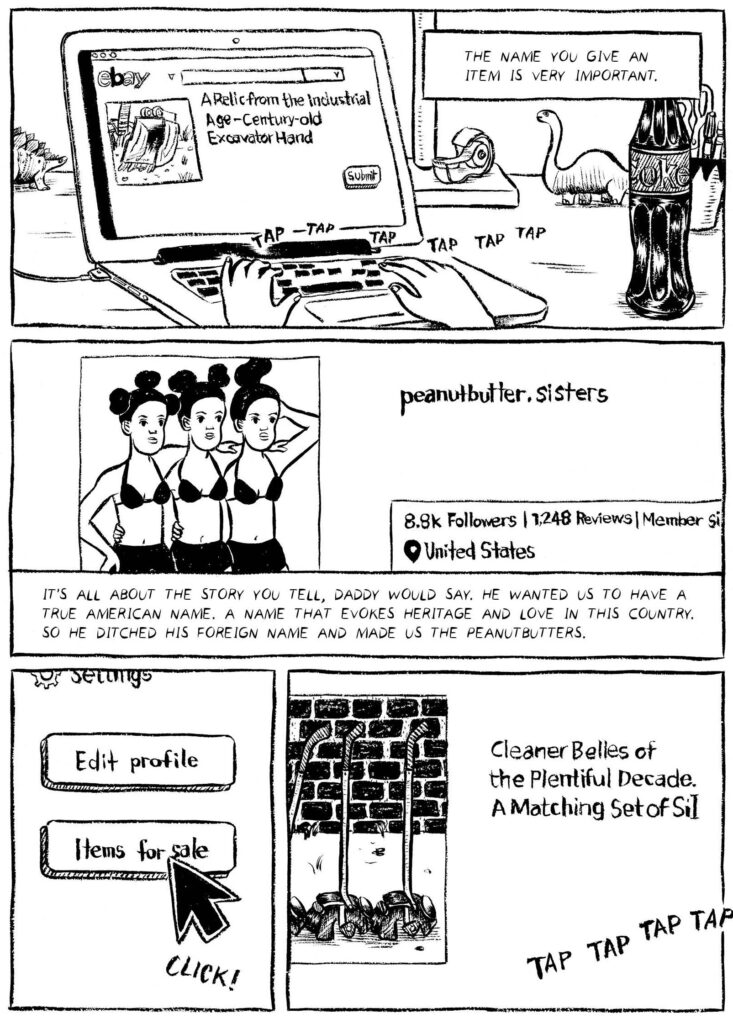

Rumi Hara: The idea of them is kind of old. Back in 2009 or 2010, I was still living in Tokyo, working as a translator. Someone invited me to this printmaking workshop and the instructor asked us to bring a sketch to make prints with. I came up with these nude triplet figures, and I was like, “This is so much fun to draw. I want to draw more of them.” So I made more prints. I did etching. I made a one-page comic. Then in 2019, I had a chance to go to Short Run Seattle, the comics festival, which was kind of the first deadline. I was like, “Oh, my God, I have to actually make this into a comic,” because I told them that I was going to debut the short story there. I finally pieced all the fragments together and figured out who they were.

RA: Do you feel like you know them, what they personify and who each sister is on their own? Did you have some sort of back story already? With Jaime Hernandez and his characters, I feel like he knows every single thing about them and where they’re going.

RH: They keep evolving, even after making that story. Sometimes they’re three-in-one, and other times they’re totally distinct and they compliment each other. Georgia is the organized, responsible one. When they travel by hurricane, she’s the one who says, “Ah, did we pack this? Did we pack that?” The second one, Alabama, she doesn’t say much, but she’s the secret leader because she’s the one flying the sisters and leading them to safety. And Mississippi, the oldest one, she’s an energetic person.

RA: A lot of your stories, especially in this book, talk about place, and that is like its own character. What’s your approach to talking about a place and documenting it? Is it organic or does where you live inspire you?

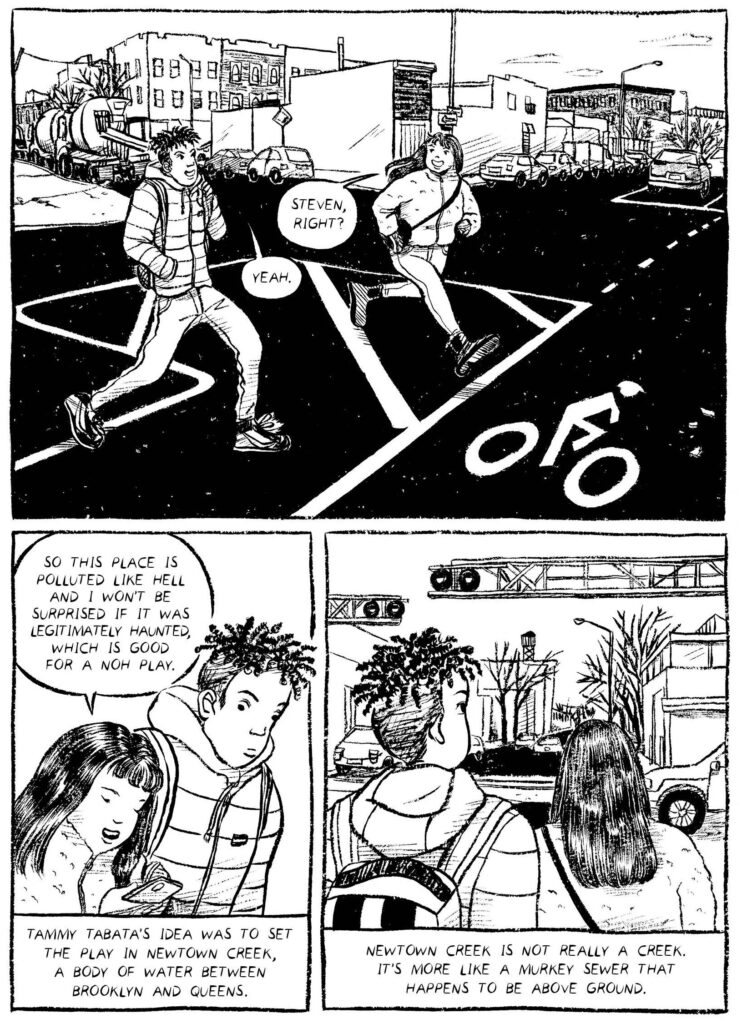

RH: Because I’m not from where I live, I notice a lot of things and I think about how I fit in. Even when I’m in Japan, I don’t feel totally at home because I’ve moved around so much. New York City is so big, it took me a while to find my perspective on it. I lived in Queens, and I had a studio in Brooklyn, so I would walk three and a half miles to my studio every day. Over the years, I started imagining what could happen in this landscape that I know so intimately. It’s gross, but it’s kind of amazing too. By the time I get to my studio, I have dust stuck to me and I have sand in my mouth and it’s terrible. But at the same time, we all loved it. So I wrote a story about that place, too.

RA: I like how you’re talking about being Japanese and not fully feeling what that is. How you think, “Am I Japanese enough? I’ve been living in America for such a long time. Am I American enough?” Tammy Tabata’s story brings that up, as well. What inspired you to make that story?

RH: The inspiration for the Tammy Tabata story comes from living in New York City, where people come and go. I had a friend who I used to walk around with a lot, but he moved away. So I was thinking, “I want to do a story about two friends walking around,” and it started that way. But I wanted to give Tammy a little bit of my memory too, how I used to live in Atlanta as a kid. You live in a place and observe that culture and you become that person. Just because you’re not from there doesn’t mean that it doesn’t change you.

RA: I’m curious about your illustration style. I know that you come from the illustration world, and the Peanutbutter stories just feel so magical and adventurous. I want to know more about how you go about making a page because as cartoonists, we learn certain rules, like tangents and panels. How do you approach a page? Is it more of a feeling or is there an organized way of doing things?

RH: I do a lot of sketches and then tighten them, mostly in Photoshop on my computer these days. I tighten the sketches of a page until it looks perfect—with all the details in it and everything. And then I print it out, put it on the lightbox, put my good paper on top of it, and then start inking. By the time I’m inking, I’ve drawn it so many times, I know exactly what I’m doing. That part’s the most fun, because I don’t really have to think about it.

RA: How big a sheet are you inking on?

RH: Most of the time it’s letter size or A4. I use this paper that comes from England. I think they make it in India—khadi paper.

RA: Is it toothy or is it smooth?

RH: It’s pretty textured, so I like it a lot. It takes ink really well.

RA: And do you do the text with a brush too? On 8 x 11, it’s hard to do text with a brush.

RH: The text is digital. I made a font based on my brush lettering, and all the text is added afterwards.

RA: I was also thinking about your approach to dialogue, because I love the interactions between the three sisters, and those unique personalities shine through. Where does your approach to dialogue come from?

RH: Dialogue is hard. Sometimes I use real dialogue from a conversation that I had with someone. But most of the time, I’m just playing out the scene in my head, letting the characters do their thing, and I’m watching.

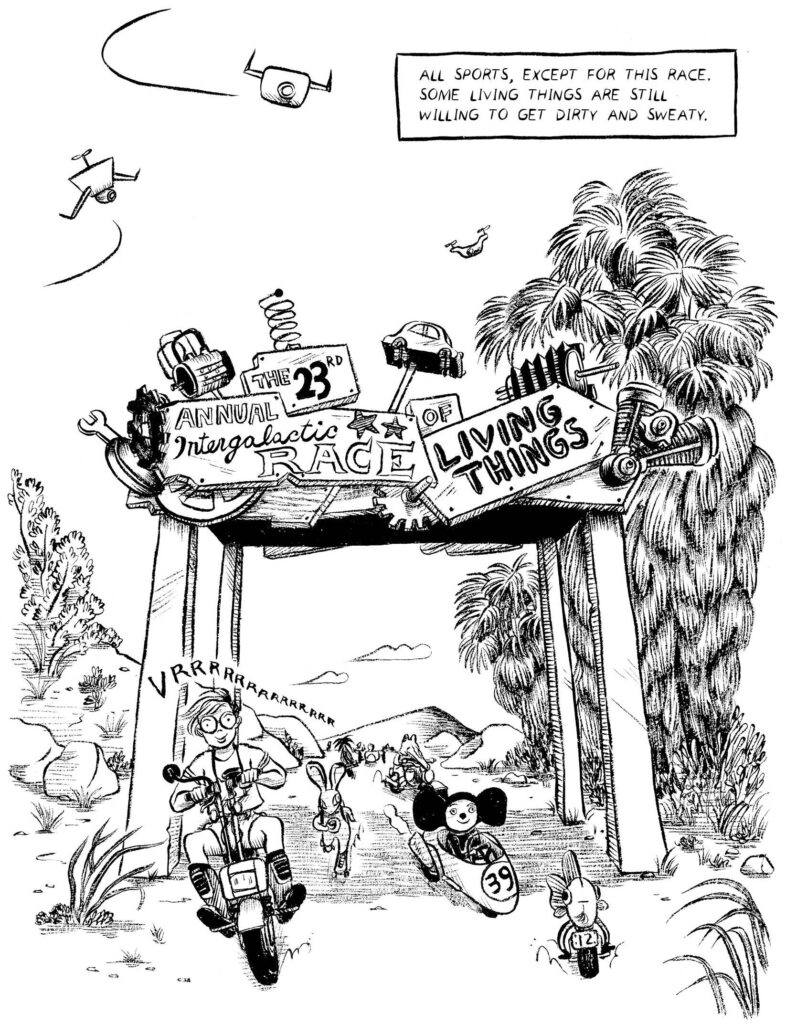

RA: One of my favorite things is how you invent aspects of worlds, like the hurricane, the whale riding. I wonder where these ideas come from, and how you give yourself permission to run with them?

RH: I think I just do. I don’t really have to show my comics to anybody, so I just let myself do whatever I feel like. Sometimes when I get an illustration commission, I’m like, “Oh, my God, I have to be proper and decent.”

RA: In comics, nobody is proper and decent.

RH: Yeah. I don’t have to show it to anybody if I don’t feel like it. It’s a great playground.

RA: I like how you said, “In comics, no one’s going to see it.” That’s what a lot of cartoonists think, and that brings up so many wild experiences in storytelling. That’s another cool thing about your book, is that it brings out stories that nobody else is telling.

How does the art world in Japan differ from the US and how does that affect your art?

RH: I think art education is especially different. In the US, you learn a lot of methods and theories, which is really helpful. I didn’t really go to art school in Japan, but I took some art classes, and the instructors taught in a more intuitive way. The advice you get is like, “This line should be flowing better,” or, “your composition is a little off.” It’s more spontaneous, which is not necessarily helpful when you’re starting out. But I felt like it was helpful to learn all the basics first.

RA: When a story is rooted in personal elements of life, how do you infuse the fiction into it?

RH: It’s mostly all fiction. I like making fiction because I can do anything I want with it, and it’s more fun for me. But the one thing I did in Nori was think about Noh, traditional Japanese theater, dramas with the mask and everything. A lot of Noh plays have this structure that involves a dream, and I wanted it to be kind of like that.

Nori walks around and goes on an adventure. She runs away from Grandma when she wants to, and always encounters some kind of fantastical stuff in a dreamlike sequence. Sometimes I try to learn from existing narrative structures and see if I can incorporate that and play around with it in comics. I also try to think about the emotions. Even though something fantastical is happening, I always want the feeling to be there, because I guess that’s the non-fiction part, all the feelings.

_______________________________

Rumi Hara’s The Peanutbutter Sisters and Other American Stories is out now from Drawn & Quarterly.