In Praise of the Dream-Logic of Speculative Fiction

Sophie Mackintosh on the Art That Takes Us Into Uncharted Territory

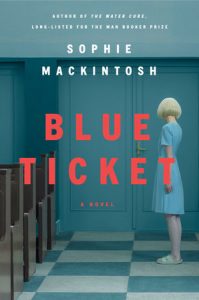

When I was writing Blue Ticket, at various points I thought about the works that had shown me what speculative fiction was really capable of, beyond idea and into language, into feeling and beyond.

I thought too about all the alternate possible novels I could have written with its idea; some more important, some better, some worse. They are not the book I ended up writing. They are not the book I wanted to write. In the end the hypothesis of the central premise (a lottery that decides whether you will have children or not) was a tool that allowed me to get where I wanted—a woman reckoning with her body and with her mind—and distanced it from me, so that I could see it more clearly.

Concepts in fiction can be more valuable as a springboard, rather than as the whole picture. A way to see differently. We tend to think of dystopia in terms of a warning system, something which delineates a clear line from here to there. But what if no line is revealed? What if we’re just—bafflingly, thrillingly—there?

In reading as much as writing, logistics seem less interesting than setting. The stages of my speculative worlds have more in common with my own dreams and inner life than with the predictions of futurologists. It gives me comfort to think of these other worlds. Something to step into. Something reformed from the images and impressions we have all been collecting every day of our lives without realizing.

In the philosophical and tender novel The Flame Alphabet, by Ben Marcus, the speech of children has become fatal to adults, and so the father of a teenage girl must seek out to find a cure for his dying wife. A little close to home now, but until recently, such a plot was dystopian. We think we know what to expect, but then the uncanny rhythm of the language, and a narrative which refuses to operate under the rules, confounds our expectations.

I will concede that this is not necessarily what you always want from a reading experience. But these strict ideas of what a dystopia is, what a dystopia should do, aren’t the fault of readers—a successful genre can box itself in with replicas until everyone wearily believes they’ve seen it all. Instead of being suspicious when books go off-course, though, perhaps we should embrace it.

In “Waxy,” a short story by Camilla Grudova, the narrator tells us, “It was frowned upon to be Manless.” It’s almost our world—almost!—but everything is grease and tinned food and chemicals, both anachronistic and post-apocalyptic, and all this is never explained. There’s something terrible in the background never talked about. It throws us uneasily off-centre, but we accept it. Somehow we forgive strangeness more in short stories, where maybe we are not so anchored to the concept of the real, where we have made less investment of our time and emotion.

*

Cygnet by Season Butler is a dystopia-not-quite-dystopia. The Kid is a teenager living amid the old inhabitants—the Swans—on an island separated from the rest of the world. The sea is washing their home away from them, and the world the Swans have willfully turned their back on is one of uncertainties and difficulties that we recognize.

We expect dystopian fiction to build a world, but sometimes introspection shows more. We see our own anxieties unfold—grief, and climate change, loneliness, and age. There’s none of the blockbuster violence we expect from dystopia here, no unnecessary exposition. Instead we’re reminded of how speculative fiction has the potential to move us, deeply, when it takes us in unexpected directions. How much, we realize, we need to be moved.

*

What I do believe in:

I believe in simplicity, in elegance, in absurdity, in conundrums. I believe it’s sometimes nice to be confounded. I believe in letting go of certainty. I believe a novel is only one side of a story that can refract in infinite ways.

*

In Census by Jesse Ball, a man learns he is suffering from a terminal illness, and so takes a job as a census-taker in order to take his son on one last journey. The towns are not named, the purpose of the census is unclear. It’s abstract, written like a fable, the focus on human nature rather than world-building.

In the film The Lobster by Yorgios Lanthimos, when a person becomes single they are sent to a mysterious hotel and required to find another partner, or they’ll be turned into an animal. The rebel singles run away to the forest and dance grimly, hilariously, to techno in the rain.

I didn’t find myself bogged down in the logistics of the animal-transforming process, or demand to know more about the larger world, in which such a system developed. Similarly, I didn’t find myself questioning unexplained details such as the tattoo that the census-taker puts on the ribs of participants. Sometimes beauty can be reason enough.

In such an uncertain world it’s understandable that we can want books to say—look, this happened and then this happened, and this will happen now. You know the pattern of this, you know how this goes, and how it ends. I guess in the end it’s just that I want everyone else to delight in the unexplained, the unexpected, and the unapologetically strange—how they can be so much more than the same story told again. I don’t want to see the rabbit come out of the hat.

I’m working on a historical fiction novel at the moment, which nobody can call dystopian. But I was drawn to a change in genre for the same reason—the options here to imagine and reimagine are endless, but with the caveat that I’m not positing a future, just taking gleeful license with the past. Historical fiction is also totally speculative after all, ripe with possibility as anything involving robots and skyscrapers. In the end, that possibility is what will always draw me back.

__________________________________

Blue Ticket by Sophie Mackintosh is available via Doubleday.