In Praise of Famous Losers: On Kurt Cobain, Beck, and the Idols Who Mythologized a Subculture

Benjamin Villegas Remembers the Antiestablishment Allure of the 90s

Being a loser was never a choice in the neighborhood I grew up in, a dreary city suburb almost entirely devoid of opportunity. The main drag had once been an old vineyard dotted with houses that orbited around a foul-smelling municipal slaughterhouse. In the 70s, the earth and the vineyards were replaced by concrete and apartment blocks, and thousands of families from humble backgrounds crowded into the neighborhood.

In the early 80s, my parents started a family while the country saw the start of a new political regime. The fascist tyranny that had held Spain in its iron grip for 40 years gave way to a shaky, inexperienced democracy in desperate need of renewed cultural models. Without the dictatorship’s censoring firewall, American pop culture spread like a virus across all strata of Spanish society.

The few television channels that illustrated my life at that time packed their meager schedules with series like Dallas, Miami Vice, or Hill Street Blues. These shows introduced me to the landscapes and conventions of Texas, Florida, and Illinois. The palm trees and sunshine of Inglewood and Beverly Hills were regular destinations in my childhood, thanks to Magic Johnson and Axel Foley. Once I turned nine, my favorite movies had me fantasizing about bowling alleys, drive-throughs, and diners. Despite having almost never left my little town, these were the places I envisaged for my future teenage years, brimming with success, fun, and vanilla Coca-Cola.

And then came the 90s.

The new decade smashed into my life like a speeding monster truck, its king-size wheels making light work of the lacquer and glamor that had seasoned my early years in the 80s. My obsession with the West Coast headed a thousand miles north, settling in the obscurity and cold climates of Washington State. Shaken to the core by my weekly fix of Twin Peaks, I was captivated by the dissonant guitar playing of Soundgarden, Mudhoney, and Nirvana, which were to pave my yellow brick road. I slipped on a pair of Chuck Taylor All-Stars and set foot on my own path, bound for Oz.

At that time, my neighborhood was a hive of junkies. As kids, we had to dodge syringes while we played. AIDS was all over the news and no one in our community was left out of the fray. Parents were terrified that a careless footstep could leave one of their children with a fatal illness. The park was no longer a fun place to be. We gradually left it behind us and began meeting up by the old slaughterhouse, right in the center of town.

As a business, it was now a pathetic shadow of its former self, yet it was still a terrifying place to behold. Its towering walls seemed to rise up into the smog. My mother and I walked past it every day on the way to school. I remember the sounds and the sense of foreboding it exuded. I remember the blood flowing out from under the main door. In winter, any snow that settled was stained red like a Slush Puppie. I remember the day they demolished it and began construction of a cultural center on its foundations. It was April 1994, and Kurt Cobain had been dead for two weeks.

Much has been written about how Nirvana’s songs gave voice to the weariness and resentment of an entire generation. In my case, the humble beginnings of Cobain and his companions resonated uncannily with my reality. I had also suffered the weight of growing up in a working-class, testosterone-soaked environment. Sensitivity and creativity were not widely touted values, and the idea of these being cultivated and respected was the stuff of utopian wonderlands. Finding out that a group of losers had managed to get out of their dead-end town and conquer the world thanks to their art was simply awe-inspiring. Suddenly I had a dream. Something to aim for. Without giving it much thought, I set up my first band.

It was more like a balloon left to shrivel up after a party, rather than popping in a blaze of glory.

From that moment, everything we did was pure anomaly. We were three 14-year-old kids with no musical instruments or training. No one in our families had any musical connections. There were no garages in our neighborhood and nowhere you could play live. We didn’t care. We began writing lyrics and thinking up names for the band. We all worked crappy jobs until we could scrape together enough money to buy a third-hand bass and drum kit. Rehearsals took place in the changing rooms of a small carpenter’s workshop. The employees would strip off, shower and dress while we practiced.

For each session, our frontman had to pick up a borrowed guitar and return it when we’d finished. We shut ourselves off from our environment and communed with something that was happening 5,500 miles away. We put on jeans and flannel shirts in the middle of a Mediterranean summer. We spoke of our idols as if they went to school with us. As if we knew them. We created a bubble. Our bubble. But as we all know, every bubble has to burst eventually.

In my case, I have to say, I never actually felt it burst. It was more like a balloon left to shrivel up after a party, rather than popping in a blaze of glory. That is the best analogy I can think of to define my musical career: a shriveled balloon surrounded by other shriveled balloons strewn across the floor after a party.

Throughout my life I have devoured movies, music, and books that mythologize the figure of the loser, turning them into winners. The Revenge of the Nerds was one of my favorite of all loser flicks. Marty McFly, Daniel-San, or sports people and teams like Eddie “The Eagle” Edwards and the Cubs all contribute to the theory.

In pop, songs like “I’m a Loser” by the Beatles or “Even the Losers” by Tom Petty and artists like Sixto Rodríguez—aka “The Sugarman”—simply serve to reiterate that mythification. But it was the explosion of alternative rock in the 90s that took this metamorphosis to a higher plain. Kurt Cobain, Rivers Cuomo, and Beck (author of the “ Loser” anthem) helped to transform “loserism” into a profitable global trend.

That’s why I like to talk about “real” losers. I mean the 99 percent of bands that consume, create, play, record, and sustain the 1 percent that reaps all the success and profits in the music industry. It was while I was laying claim to my place as a “real” loser that I decided to write the biography of a band that exemplified the concept, a group that could tell the story of the 99 percent of bands that don’t amount to anything. My guiding inspiration was my own life experience as a loser, and I found that my role models were 4,000 miles away in a country I had never set foot in.

I flew to El Paso (TX) and interviewed nearly all the musicians that contributed to the city’s punk scene between 1979 and 1994. Talking with them, I realized my story in Barcelona in the late 90s could have been theirs. We were all “real” losers. We were all the same kind of shriveled balloon left behind on the floor of music history.

During the two years I spent traveling around Texas gathering information, I noticed a shift in my lineup of music heroes. Groups like Nirvana or Mudhoney made way for Teenage Popeye, the Rhythm Pigs, and Foss. Mike Nosenzo, Greg Adams, and Arlo Klahr are my idols now. Bands and musicians that enjoyed less success, had less impact but had the power to get this thirty-something loser raving about punk again.

No one would have given a dime for my chances in 2015, when I touched down in Dallas with the impossible challenge of locating a non-existent band. It was Mike, Greg, Arlo, and the other figures from El Paso’s punk scene that helped me to track them down.

“The band might not be real, but its story certainly is,” they said.

Maybe being a shriveled-up balloon isn’t so bad after all.

__________________________________

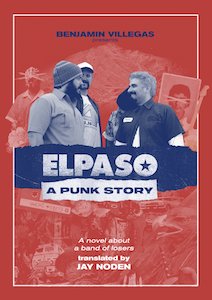

ELPASO: A Punk Story is available from Deep Vellum Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Benjamin Villegas. Translated from the Spanish by Jay Noden.

Benjamin Villegas

Benjamin Villegas was born in Spain. He was named after Fantastic Four's The Thing, and grew up in a household full of comics, music, and movies that shaped his taste for American pop culture. He is a musician, illustrator, audiovisual producer, and graphic designer. He is also the author of Huele como a espíritu posadolescente (Smells Like Postadolescent Spirit).