Herbert Matthews, the correspondent of the New York Times, was one of the most familiar figures in our office. Tall, lean, and lanky, Matthews was one of the shyest, most diffident men in Spain. He used to come in every evening, always dressed in his grey flannels, after arduous and dangerous trips to the front, to telephone his story to Paris, whence it was cabled to New York. Like his colleague of the New York Times, Lawrence Fernsworth, who had lived in Barcelona for a decade and knew Catalonia as few foreigners alive, Matthews was exceedingly suspicious of me and the Foreign Press Bureau. For months, he would not come near us except to telephone his stories, for fear, I suppose, that we might influence him somehow. He was so careful; he used to spend days tracking down some simple fact: how many churches in such a such small town; what the government’s agricultural programme was achieving in this or that region. Finally, when he discovered that we never tried to volunteer any information, even to the point of not offering him the latest press release unless he specifically requested it, he relaxed a little.

Matthews had his own car and he used to drive to the front more often than almost any other reporter. We had to sell him the petrol from our own restricted stores, and he was always running out of his monthly quota. Then he used to come to my desk, very shy, to beg for more. And we always tried to find it for him: both because we liked and respected him and because we did not want the New York Times correspondent to lack petrol to check the truth of our latest news bulletin.

I came to admire terribly this passion for fact. I was irritated at first, I suppose, not to find myself believed. But I came to see that this, after all, was the way to get the facts into print, to have the men who sent them convinced of their accuracy because they themselves had got them. I have to smile when I hear stories of how we “influenced” the foreign correspondents. And now, of course, as one looks back on their coverage, one sees that if they erred, it was on the side of understatement. Just as our Republican “propaganda” was pitched far too low, as we now see since the dictators have seen fit to reveal how they tricked the democracies.

A great favourite in the Foreign Press Bureau was Ernest Hemingway. He knew Spain very well, knew it and felt it perhaps more than any other correspondent. Sometimes I used to think that he loved it for the wrong reasons, or at least for reasons which seemed very strange to me, but at any rate he loved it and under-stood it when the war came.

As time went on, we began to suffer more and more from this curse of sensation seekers.He too had his own car, and I think he got petrol more quickly than any other correspondent, for all the girl secretaries in my office adored him and as soon as he walked up the stairs and opened the door, they would scurry around to find him permits and petrol slips.

Of course, as Hemingway became a friend of ours, we used to have great arguments, especially about bull-fighting. I, like many Spaniards, have always loathed bull-fights. The people of Spain were brought up, in a world dominated by the landlords and feudal aristocrats, to find release from their hard and tragic lives in the drama of death and futility set forth so clearly in the bull-ring.

With the beginning of the war, bull-fights vanished by common consent. True, we needed the animals we had for food and the bull-fighters all went to war; there was a battalion of them at the outset. But it was more than that. The Spanish people now faced the future with hope. They were in love with life, not death. The bull-fight went out of the pattern of our existence. We no longer needed to forget our hopeless existence watching the matador—for we believed in the future.

We all liked Hemingway enormously, and everyone in the Foreign Press Bureau disliked and distrusted a certain London journalist who, during part of his stay in Spain, pretended to be sympathetic to the government, a piece of fiction he dropped when he went home to London. He would always appear in my office in ancient ragged clothes, dirty shirts, mud-caked shoes, trousers stiff with grease. We considered his strange clothing an insult for we knew that in London he was something of a dandy. Madrid, Valencia, and Barcelona were perfectly civilized cities—even if they were Spanish. This man always talked and behaved as though the Spanish people were some strange, benighted tribe of savages engaged in a rather silly, primitive type of bow-and-arrow contest. He was one of those Englishmen who consider any other race inferior and he had not even the grace to blush for what his government was doing to Spain.

At about this same time, I began to see many of the visitors who came to Spain for reasons other than that of news gathering. I decided it cost me nothing to be amiable and helpful, and it might do Spain a great deal of good. Of course, I learned to take great precautions. Credentials had to be checked carefully. Sometimes I discovered a person of great importance, then we put cars at his disposal and outdid ourselves to be kind. More often I discovered our visitors were simple “war tourists.” For, as time went on, we began to suffer more and more from this curse of sensation seekers. I had to put a careful check on my feelings. For I felt it simply monstrous that some people could come to Spain only to watch us die.

The stream of visitors kept increasing. We had politicians who wanted to curry favour with voters at home, and politicians who came to gawk at a suffering people and went home to fight our battles. We had writers and poets who came for inspiration and to find the truth; and writers and poets who came because at one time it was distinctly unfashionable in literary circles not to have visited Spain. I do not mean to say that most of the people who came to Spain did not come because they wanted to help us. Most of the stream of people who went through my office were honest men and women who worked hard and bravely for us in their own countries after they went home. Spain owes its foreign friends a debt it can never repay.

There was, for example, Dorothy Parker, dark-haired, small, and charming, who came to Spain with her husband, Alan Campbell. They, like nearly all my visitors that autumn, brought a lift to our hearts. They realized the difficult situation in Spain, wanted few favours, asked intelligent questions and behaved exceedingly well under trying circumstances. And they understood.

__________________________________

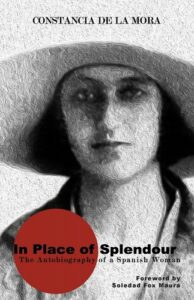

From In Place of Splendour: The Autobiography of a Spanish Woman by Constancia de la Mora, with a foreword by Soledad Fox Maura. Used with the permission of Clapton Press.