In One of Her Last Interviews, Joan Didion Talks to Hari Kunzru About Loss, Blue Nights, and Giving Up the Yellow Corvette

“Something happened—the ease of my relationship with language disappeared.”

In September 2011 I went to visit Joan Didion at her apartment on the Upper East Side. I was there to interview her for a British women’s magazine about Blue Nights, her recently published memoir. We spoke (among other things) about grief, the aesthetics of failure, California and (at the request of the editor) about her friendship with the Redgrave family. Since most of the interesting stuff didn’t make it into the piece, here’s the full transcript.

*

Hari Kunzru: To say I enjoyed Blue Nights seems like the wrong term. I admire it, very much.

Joan Didion: Thank you.

HK: When did you know you were writing that? Was it absolutely continuous with the notes you were taking for The Year of Magical Thinking?

JD: No. Not at all. I was through Magical Thinking. It had been turned into a play. And [I] was trying to think—the play ran for a year or two, and obviously I was going to have to think of something else to write, and I decided I wanted to write about children, attitudes towards having children. And I started writing about children and of course I ended up writing willy-nilly about my own child. At that point I thought it was getting very hard for me to write, and I thought—you don’t have to do this, you can give Knopf back their money and not do it. So I thought that for a couple of weeks and then something else occurred to me and I wrote it down, and then I saw it was not totally about children, but about other stuff like getting older and I pushed on.

HK: When you say you pushed on, I’m interested in—how you begin—how you’ve begun books in general and this one in particular. You take notes—

JD: That one. I didn’t have any idea what the book was going to be about so I wasn’t really taking notes of any use. Then I was very taken—somehow the phrase “blue nights” occurred to me—and I thought you could call it Blue Nights. This sounds crazy. That you start a book because you have thought of two words that make you happy.

HK: It unfolded from the title.

JD: It totally unfolded from the title. And so it doesn’t actually go anyplace linear, because it unfolded from the title.

HK: It seems like it’s shaped like memory.

JD: It’s shaped like memory.

HK: You have these very precise fragments that you pick away at, you make a circuit around them.

JD: And then come back.

I thought you could call it Blue Nights. This sounds crazy. That you start a book because you have thought of two words that make you happy.

HK: “When we talk about mortality we’re talking about our children.” I wonder if you could say a little more about what you mean by that.

JD: I’m not sure what I mean by it. I actually wrote it down. And I started thinking—it’s a banal thought, of course—we’re talking about our children because we’re talking about fear of our children dying, hostages to fortune. Our children are hostages. It was just a flitting from one angle on a thing to another.

HK: You talk quite a lot about frailty, which I’d like to come back to later. This notion that—you have a child—

JD: And you’re never not afraid.

HK: That’s an extraordinarily frightening thought. I haven’t got any children yet. I’m thinking about having one. And that’s precisely what I most fear.

JD: It’s terrifying.

HK: About the process of becoming a parent—

JD: It’s actually terrifying. A lot of people have that feeling about their dogs. And if you’re the kind of person who’s going to have that feeling about a dog you’re definitely going to have that about a child.

HK: One of the questions that seems to come up for you when you’re trying to understand Quintana’s childhood is the environment you raised her in, the film colony. There’s the extraordinary story about taking her to see Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and her response is “I think it’s going to be a big hit.” Did that—you obviously found that striking—you were expecting a direct and emotional response to the movie’s story. How did you read that? Was that her protecting herself from feeling something? Did you worry she’d become crass in some way?

JD: I don’t know what I thought. It wasn’t a cause of worry to me. It was just a wonder. Everybody she knew would talk that way. It was striking to me that she’d picked up so much. She was born in ’63. She was eight or nine.

HK: You think about the hotels a lot, about taking her to the Dorchester, the Plaza. But you very strongly reject the notion that it was a privileged childhood.

JD: I don’t think it was privileged. I felt very strongly that I didn’t want people to read this about her and think this is an overprivileged child. I think there was a lot in her life that worked against privilege. She had a rather difficult life in a lot of ways.

HK: Being adopted?

JD: Yes. And not being—the fact that she had picked up a certain ability to get along in the world that she’d been placed down in didn’t seem to me to be something that should be held against her. [laughs]

And I started thinking—it’s a banal thought, of course—we’re talking about our children because we’re talking about fear of our children dying, hostages to fortune.

HK: You seem ambivalent about seeing her functioning so smoothly in some of those situations.

JD: I was ambivalent about it.

HK: Was that because you didn’t want her to grow up so fast?

JD: I didn’t want her to grow up at all! I wanted her to be a baby forever.

HK: So the end point was when you brought her back from the adoption, the scene in the restaurant in Hollywood, where she sat on the table in her bassinet and you felt everything was perfect.

JD: Yes.

HK: Back to this word frailty. You write very movingly about it. But it seems [to] me that throughout your works there’s been this anxiety and a sense of dread without an object, it’s one of the strongest tones that I get from your writing of the sixties and seventies. I think it [is] what’s made you such a good writer about California. There’s something very specific to California about that dread—anyway—now the dread has an object. In a way, the worst has come.

JD: Right. It’s an odd time. It should be kind of a liberating time. It’s not. I’m no longer hostage.

HK: You’ve faced it.

JD: Yes.

HK: And you’re still here.

JD: It doesn’t seem to work that way.

HK: How does it work?

JD: You still have that floating anxiety.

HK: And you feel that’s transferred itself to—the physical—the skateboarder coming down the street, the taxi?

JD: Exactly. My fear for Quintana’s safety has transferred itself to fears for my safety.

HK: You write about how peculiar that is, because sometimes you forget this is the body you’re in now, you think of yourself as a younger person. I read an old interview with you this morning, from when you were living in California [“Joan Didion: Staking Out California” by Michiko Kakutani, in Joan Didion: Essays and Conversations] which said that the 1969 yellow Corvette Stingray Maria drives in Play It as It Lays was actually your car.

JD: It was my car.

HK: Do you still feel connected to that woman? The woman who drove along the coast road to Malibu in a yellow Corvette Stingray?

JD: No. At some point in the past year I think I twigged to the fact that I was no longer the woman in the yellow Corvette. Very recently. It wasn’t five years ago.

HK: When you said you “twigged to that,” was that a moving on, a sense of loss—

JD: Actually, when John died, for the first time I thought—for the first time I realized how old I was, because I’d always thought of myself—when John was alive I saw myself through his eyes and he saw me as how old I was when we got married—and so when he died I kind of looked at myself in a different way. And this has kept on since then. The yellow Corvette. When I gave up the yellow Corvette, I literally gave up on it, I turned it in on a Volvo station wagon. [laughs]

HK: [laughing] That’s quite an extreme maneuver.

JD: The dealer was baffled.

HK: The Corvette driver would mutate into the Volvo driver. Was that because you were leaving California?

JD: No, we had just moved in from Malibu into Brentwood. I needed a new car because with the Corvette something was always wrong, but I didn’t need a Volvo station wagon. Maybe it was the idea of moving into Brentwood.

HK: You were really trying to embody that suburban role. So the Corvette was the car you were driving down the foggy road and trying to work out where the turn for your drive was, and where was just a steep cliff.

At some point in the past year I think I twigged to the fact that I was no longer the woman in the yellow Corvette.

JD: Yes.

HK: There are many sudden turns in the book but one I liked—one you got me with—was you write this quite sentimental passage about objects that have memories for you, end the chapter and then announce at the beginning of the next chapter that you “no longer value mementos in that way.” That was very startling. And yet we’re here in your apartment, surrounded by your things. Your books and photographs. At one point in the book, you’re quite resentful of—

JD: Things.

HK: I half expected to find you in some spare, empty space, having done some kind of radical clean out.

JD: That was the moment when I thought of moving into Annie Leibovitz’s apartment. [Before the interview we’d talked about London Terrace and the apartment Leibovitz and Sontag had shared. She’d seen it when Leibovitz was moving out to her famously disastrous town house. She liked the emptiness of it.]

HK: So does that mean you’ve come to terms with objects?

JD: I haven’t come to terms with them. I don’t know what to do with them. There’s no resolution to it. I don’t want to just throw them out.

HK: You can’t take it all to Housing Works.

JD: No. I guess. Some of them wouldn’t be any use to Housing Works. The physical act of cleaning out my stuff seems to be beyond me.

HK: It takes people in different ways, doesn’t it? Some people seem to need to have stuff bagged and out the door before they can process anything.

JD: When my mother died—my mother died in Monterey. My brother had a house in Pebble Beach so he was there. I knew immediately, because mother had secretly told me, when she died she wanted to make sure he didn’t put everything into a dumpster and get rid of it. She wanted certain things to go to certain children, grandchildren, nephews; she wanted me to take care of that. And so I endeavored to do that. I flew out to California, I insisted to my brother that we were going to do this, we were going to divide up her furniture and so on, so he was so unwilling to do this that I ended up sending most of the stuff to this apartment. I’d sent everything that was claimed to that child, and the rest of it stayed here. It’s still here. I don’t want it.

HK: But the filing system has broken down, the processing system.

JD: Yes.

HK: You wrote about Natasha Richardson, and you’re friends with Vanessa Redgrave. Do you find any value in comparing your grief to the grief of a friend?

JD: Vanessa and I became very close during the time we did the play. Actually we’d been weirdly close before because I was a friend of Tony [Richardson]’s. And so I was very fond of her. And then we became very close during the time when we were doing the play. Well, she was doing the play. I wasn’t.

HK: You were drinking cocktails in the vicinity of the play, from your account.

JD: Yes [laughs] and when Natasha died, we did talk. Obviously we did talk a lot about that. I’m not sure—there’s no comfort in talking.

HK: Not in community?

JD: No, I don’t think so.

Something happened—the ease of my relationship with language disappeared. Now, what that is I have no idea.

HK: People do go to groups don’t they, to talk. It’s never specially been an impulse of mine.

JD: It’s not mine. I’ve never done that. Vanessa was a comfort to me, just the fact that she was there.

HK: She has an extraordinary presence. I knew her brother a bit.

JD: Corin.

HK: Yes. I met her at a stage reading a group of us were doing for Corin [a protest against extralegal detentions in Guantanamo Bay]. She was this—whirlwind of a woman—I think she was particularly distracted when I met her, she had a million things on her mind—she carries her own concerns into the room.

JD: Entirely, entirely.

HK: I found it easiest just to sort of surrender to the atmosphere that she had decided to create.

JD: She did Magical Thinking not only at the Booth in New York, but at the National Theatre in London. When she was going to do it at the National Theatre she asked me to come over for a week of rehearsals. So the day I arrived in the rehearsal room, I walked into the rehearsal room and the first thing I know is, to act out her pleasure at my arrival she’d thrown her bag at me. Suddenly I realized there was blood running down my leg. I spent the rest of the week making daily visits to the National Health nurse. [laughs]

HK: She damaged you with her extrovert gesture. Was she mortified, or did she not notice?

JD: I never told her why I was going to the nurse’s office.

HK: I was very struck by the passage when you reproduce a note you’d taken for a piece of fiction with x’s marking various placeholders and demonstrate that ease with which you were—in a way—able to fill in those blanks in response to—you say you thought of it as listening to music. And you say that’s now gone. That facility. When did that change for you? How is writing now?

JD: I think it changed when I was writing this book. I’m not saying it had anything to do with the particular book. Something happened—the ease of my relationship with language disappeared. Now, what that is I have no idea.

HK: Is it just ease in producing words, and not having them mean too much?

JD: Ease in producing words. But they did mean something. Now, in point of fact when I mention this to certain people, they will say to me—they name a date ten years before when I was making the same complaint that I’d lost my relationship with language, and this may be so. But I feel it now.

HK: You write that for a while you encouraged that tendency in yourself, because you saw it as a new directness. And directness seems to be an important quality for you in prose.

JD: Yes.

HK: And then you—you decided this wasn’t the case at all. You write “I see it now as frailty.” What do you mean by frailty? The end of this facility?

JD: That it’s a failure. As opposed to a technique.

HK: What kind of a failure?

JD: Specifically the failure to have a fluid relationship with language. Or with my means of support.

Fiction has seemed impossible since I finished The Last Thing He Wanted (1996), a book which I had intended to be totally plot-orientated.

HK: And yet, you’ve written a book that seems stylistically continuous with your previous work. I can tell it’s you writing. I don’t have a—maybe it’s more boiled down, more—

JD: It feels very different to me.

HK: It’s the hardest question to answer. How? What if it’s not necessarily apparent to the reader, this trace of the difficulty you had making it? [a long pause] For example, could you ever see yourself writing fiction again?

JD: Fiction has seemed impossible since I finished The Last Thing He Wanted (1996), a book which I had intended to be totally plot-orientated. I’d wanted to do a very densely plotted novel. And I did. It was so densely plotted that I had to—I think I wrote it in ten weeks or something because if you stopped for even a minute you’d forget the plot. I was working—somebody wanted me to make a movie of it, and I was roughing out a draft of a screenplay of it—and even I couldn’t remember the plot. I couldn’t keep it straight. So it seemed to me that another novel was not the way to go.

HK: That “plottiness” feels irrelevant, distant now? You prefer the idea of making structures that reflect something more immediate about your experience?

JD: It feels like not the right thing to be doing.

HK: California v. New York. You agonized about giving up your California driver’s license.

JD: Got rid of it. I had to. My birthday came and I had to renew my license and I couldn’t get to California. I’d already renewed it enough times by mail. I had to show up. And so I took my California driver’s license down to Thirty-Fourth Street and turned it in. I’m a New York driver.

HK: Do you still have a lot of friends and connections in LA?

JD: Yes.

HK: Do you spend a lot of time there?

JD: No I don’t. I haven’t spent a lot of time there since Quintana was in the hospital.

HK: And your New York life? Do you see a lot of people at the moment?

JD: I see far too many.

HK: There’s a writer—I think you might know her—called Meghan O’Rourke.

JD: Oh yes.

HK: She wrote a memoir about losing her mother [The Long Goodbye (2011)]. It was one thing for her to put it down on paper. She did it very soon. And what she found was the business of talking about it, and touring, and doing interviews like this—she found that awful. She found it difficult in a way she wasn’t expecting. And I read somewhere that after Year of Magical Thinking you did quite a substantial book tour and that you found it therapeutic.

I was never in my whole life going to stop grieving for Quintana. It wasn’t a question—it was a question of are you going to live for the rest of your life. Get on a plane and live.

JD: I think I did on some level. It was almost immediately after Quintana died. Obviously the trip had been planned long before she was even in the hospital. But it did not cross my mind to cancel it because I simply didn’t know what I would do if—I mean, I was never in my whole life going to stop grieving for Quintana. It wasn’t a question—it was a question of are you going to live for the rest of your life. Get on a plane and live.

HK: Distraction is sometimes a good thing, but how was it taking questions from audiences? You must have had people standing up in audiences telling you their stories.

JD: They did. Actually it was—because they were interested in telling me their stories rather than hearing about mine, it was kind of great. [laughs] I could just lie back. I was a witness to their stories. It was a role I found very comforting.

HK: In a way, that’s the kind of work you’ve done throughout your career.

JD: Listening.

HK: This is from The White Album: “You are getting a woman who somewhere along the line misplaced whatever slight faith she ever had in the social contract, in the meliorative principle … I have trouble maintaining the basic notion that keeping promises matters in a world where everything I was taught seems beside the point.” That was, I suppose, written partly about the social upheavals of the sixties, but it also seems—do you feel that the way it’s worked out—with the loss of your husband and daughter—do you feel that promises have been broken in some way?

JD: The loss of my husband was not like the loss of Quintana because it was perfectly predictable. I didn’t predict it—but—he was of a certain age, he had heart trouble, this was an acknowledged—even by me—I knew he had heart trouble. It wasn’t a secret. He was always having something done to his heart. Anyone else could have figured out in a flash that he’d die from it. But it came as a surprise to me. That was my fault. [laughs]

HK: A failure of imagination.

JD: Yes. But Quintana’s death was out of the blue.

HK: Unjust?

JD: Unfair. I wouldn’t say unfair. Nothing’s fair. But it was an unbalanced death.

HK: And for somebody who had a skeptical relationship with—conventional ideas about the meaning of life—certainly from that passage—that’s somebody who’s having a hard time working out what it’s worth caring about—presumably that feeling’s only been augmented by what’s happened to you. I mean, is it writing that’s providing a center?

JD: I haven’t got a center. I don’t know where my center is. I don’t know where I’m going to find it. Once in a while I’ll wake up in the middle of the night and think well—I’ll have some flash of something that looks like a center, but it doesn’t signal—it’s a mirage.

HK: I have one personal question. I’m writing film-scripts with my fiancée, Katie Kitamura, also a novelist, and we’ve both read you and your husband on the subject, and I wonder if you could say anything about how that partnership worked for you. Are you writing scenes together, or—

JD: Here’s what we did. We’d work on different parts of the screenplay together. If he started it, I’d usually follow and rewrite. If I started it, he would rewrite.

HK: One to pioneer—

JD: Really only one person can make up the plot. You can’t really just sit there and talk out a plot. One person can sit there and come up with the characters. Then the other person can polish that and work out the details. It was whoever was free to start it. The other person would come up behind. Who started it really depended on who didn’t have another commitment.

________________________________

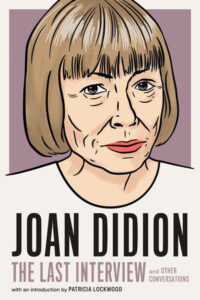

Joan Didion: The Last Interview is available from Melville House

Hari Kunzru

Hari Kunzru is the author of seven novels, Blue Ruin, Red Pill, White Tears, Gods Without Men, My Revolutions, Transmission, and The Impressionist. He is a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books and writes the “Easy Chair” column for Harper’s Magazine. He is an Honorary Fellow of Wadham College Oxford, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and has been a Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library, a Guggenheim Fellow, and a Fellow of the American Academy in Berlin. He teaches in the Creative Writing Program at New York University and is the host of the podcast Into the Zone, from Pushkin Industries. He lives in Brooklyn.