In a Time of Climate Crisis, How Can We Teach Children About Reciprocity?

Writing a Children’s Novel with Peter Alexeyevich Kropotkin's Philosophies in Mind

In 1902, Peter Alexeyevich Kropotkin—scientist, explorer, and historian—published the book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. It was meant to refute the rise of Social Darwinism, which Kropotkin saw as a perversion of the legitimate scientific theory of natural selection. Kropotkin’s findings, which he drew through observation of animal populations in Asia and Sibera, were the first to posit that species who practiced reciprocity had an evolutionary advantage. People help one another, he later wrote, not because they expect reward, but because solidarity is instinctive; natural selection favored species and societies that practiced mutual aid.

At the time, Darwin’s evolutionary theories were being used to promote the idea that competition was the driving force in nature. And this is what Kropotkin initially expected to document on his fifty-thousand-mile journey through Siberia. He studied mammals, schools of fish, insects, and migratory birds, and found that cooperation, not brutality, was the defining characteristic of the animal lives he observed.

“I saw mutual aid,” he wrote, “and mutual support carried on to an extent which made me suspect in it a feature of the greatest importance for the maintenance of life, the preservation of each species and its further evolution.”

While Kropotkin’s ideas were the first to recognize mutualism between species and altruism in evolutionary biology, it wasn’t only in animals he saw mutual aid at work. Over the course of his travels, he documented reciprocity and altruism among people as well. And in both humans and animals, he wrote about how cooperation happens without any formal organization—as simply a part of living.

As Kropotkin’s reputation as a scientist grew, he went on speaking tours throughout England, Europe, and the United States, becoming what was, for the era, a popular science superstar. He went on to publish books about biology, geography, and philosophy, and to influence generations of other scientists, writers, and thinkers, which has driven evolutionary research to this day.

It’s easy to see how, in a different world, Kropotkin’s findings could have come to endure in public discourse on evolution, instead of the sullied Darwinism of “survival of the fittest,” which came to be used to normalize aggressive and aberrant behavior.

The idea that working together is innate to all creatures is overridden by an infectious cynicism.

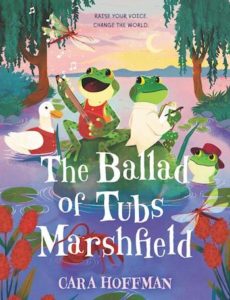

I thought about this other world a great deal as I was writing my second children’s novel, The Ballad of Tubs Marshfield. I was living at the time in Exarchia, a neighborhood in Athens, Greece, where Kropotkin’s philosophical writing lines bookstore shelves, and where his findings are played out in the form of collective housing, free community classes, political and cultural organizing, and support for refugees.

I wrote the first chapters of the book while living a few blocks from the Athens Polytechnic Institute, where a unified uprising in 1973 led to the toppling of the military junta. Mutual aid was on my mind—as was the best way to communicate ideas of altruism and reciprocity to children living now with the weight of the environmental crisis, particularly American children, who are born into a deeply stratified society and groomed for competition, consumption, nationalism, taught that things are black and white—or red and blue.

Kropotkin, though he was celebrated in his own time, is not taught alongside Darwin in school. The idea that working together is innate to all creatures is overridden by an infectious cynicism.

In Greek, the word to agree is συμφωνώ (symphono), literally “sound together,” harmony. There is an implicit and significant difference between the meaning of the words agree and συμφωνω. To be in agreement is to have the same views as another, to concur. Harmony is the process whereby separate individual notes that are not the same resonate together to collectively create something greater.

Συμφονια was on my mind as I was writing, and thinking about the different voices of frogs creating a resonance that carries distances. We have, I thought, so much to learn from frogs these days. From their disappearance—200 species gone extinct since the ’70s, which scientists believe is a harbinger of the sixth mass extinction—and from the music of their voices which have sounded on earth for 265 million years, and which convey an unquantifiable sense of calm and belonging to the human ear, conveying in chorus the health and vibrancy of land and water—or, in silence, a warning.

I don’t think a more beautiful story about reciprocity has been written.

Children alive now have the predicament of adapting to the climate crisis before them. And adults should respect the depth of this burden. Amplifying and normalizing stories of conflict, competition, and exploitation belies a crucial reality of how creatures evolve and live on Earth—together, interdependent, bred in the bone for collective survival. The most important work ahead is helping children to understand and withstand the climate crisis.

This kind of education can start very early. I think of books like Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad series, which are in every way about mutual aid and loving people who are different from you. I think of the books of William Steig—particularly Dominic, a middle reader novel about an adventuresome dog who cares for his friends, fights off a violent gang of materialists, shows his emotions, and joins others in protecting themselves from plunder. And I think, always, of Tove Jansson’s Moomin books, which were a guiding light in my own childhood. Filled with odd characters who have wildly different personalities and habits, Jansson created a world where creatures have complex emotional lives, follow no rules, and have a deep love of the forest, the ocean, and the valley where they live. One of her stories, The Hemulan who Loved Silence, tells of an outlier, an introvert, who rebuilds, over time and with much unexpected help, a ruined amusement park. I don’t think a more beautiful story about reciprocity has been written, and I can only hope my work might follow Jansson’s lead.

This is why I wrote The Ballad of Tubs Marshfield: to amplify a song of calm and belonging; to show Kropotkin’s and Darwin’s findings in the form of singing frogs and kind water rats, and optimistic bog lemmings who invent their own parachutes. It’s a story of individual creatures, who don’t always agree, acting in symfonia; a story of survival of the clever, the kind, the imaginative.

__________________________________

Cara Hoffman’s The Ballad of Tubs Marshfield is out now from HarperCollins.

Cara Hoffman

Cara Hoffman is the author of three award-winning novels for adults as well as the children’s novels Bernard Pepperlin and The Ballad of Tubs Marshfield. A MacDowell Fellow and an Edward Albee Fellow, she lives in Athens and Manhattan.