Imagining One Last Lunch with My Father, John Cheever

Benjamin Cheever Wonders How He'd Explain Donald Trump

The promise of barbecued spare ribs routed any misgivings I might have had about seeing my father again, though I hadn’t met with him—outside of dreams—since he went and died on me back in the spring of 1982.

I was surprised and pleased by the eagerness with which he accepted my invitation to lunch at the China Bowl, at its original location, 152-4 West Forty-Fourth Street. This social victory was given considerable heft by the theory that the approval of a parent is all a child needs to make her-or-his entire life a triumph. Though the theory is patently false, it’s wildly defended, and even when said child is fully grown and said parent, a feast for worms.

Besides which it’s fun to socialize with the dead because they know so little about what’s happened since they left.

There’s no WiFi in the afterlife, no newspapers or magazines. It’s a house rule St. Peter implemented after so many worthies had had their heavenly bliss spoiled by a mixed obituary or—what’s much worse—a missing obituary.

If nothing else, heaven is supposed to be just. Which is not how it looked when Judas got thirty pieces of silver and front-page notices around the world.

Iscariot made matters worse, of course, by having his write-up laminated and taking it with him everywhere. “There’s no such thing as bad publicity,” he said.

St. Peter finally had to deputize Samson to beat the shit out of Judas and put the clipping in the recycling.

Damming the current of current events turned out to be a truly heavenly policy. It also swelled the ranks of those interested in the One Last Lunch program. The dead were ignorant and therefore curious, while the quick were in a position to amuse their forefathers and foremothers with floods of trivia. Also, some artifacts were permitted. I heard about one boob who didn’t know Rome, Italy, from Rome, Ohio, but he still astounded Caesar with his iPhone 7. Julius couldn’t believe that it was water resistant.

The trouble with meeting Daddy in 2018 was that I was certain to confirm his most serious complaint about his self-pitying oldest son. “So, you’re happy?” he liked to ask, whenever we came together. “I suppose the old world is running like a clock?” Daddy took my sorrow personally, as if it were a blot on his own copybook.

And in 2018, national politics were making it hard to put on a happy face. Plus, I had a lot of friends who wanted to know what my father might have thought about rumors of the coming Rapture.

I could imagine him rolling his eyes.

I miss Daddy, but if it hadn’t been for the China Bowl, I might have cancelled. That was another great feature of the One Last Lunch program, since you could eat with people who were no more, you could also meet them at eateries that were also gone.

My father was as fickle about his restaurants as he was about his lovers, but my father was faithful to the China Bowl for decades. He liked the acres of white tablecloth, the heavy napkins. He claimed the mirror in the bathroom made him look taller and that he had once been shown to his table by Madame Chiang Kai-shek. This I always doubted, although the empress of China did live in Manhattan until she was 105. There was no arguing with his assertion that the martinis were cold and the mustard was hot.

Toward the end of his life, John Cheever used to lunch at the Four Seasons, though this seemed ridiculous even to himself. “You pay fifty dollars for a piece of lettuce,” he would say. I’m guessing that would be $125 in today’s money.

Walking west on Forty-Fourth Street, I could see the clothes people around me had on were changing in style, while the cars took on a comforting vintage look, the clangor of horns faded, and the engines had a full-throated roar. I knew the magic was working for sure when I picked out the bowl-shaped sign on the roof. On the street, I saw a brown-haired, smallish gent, in one of those suits from Brooks Brothers that were ingeniously designed to fit no man.

I’m always glad to see the people I love, because I have trouble reconstructing faces. I can summon the way they feel and smell. I can re-create the ring of a voice, but the facial features are a blur. My father could beam at you with such force that it was a surprise, and he was beaming now as he approached me on the sidewalk. I held the restaurant door for him, but he insisted I go in first. He’d lived at a time during which those with the greatest authority always went through a door last. When he went to Russia, he learned that it was safe for males to embrace, so thereafter, we embraced, though awkwardly.

When we got to our table, it wasn’t clear who should sit first, so we both stood ashamed behind our chairs. Finally, and at the same moment, we both gave up and sat down.

“We used to eat here when we came to town to buy you toys,” he said.

“If that’s how you remember it,” I said, not wanting to tumble immediately into a familiar squabble.

“I distinctly recall leaving a racing-car set with the hat check girl, because it was gigantic, almost as big as you were then and far too large to hide under the table. We bought the last one in the store, and they had to take it out of the window.”

“You bought me toys,” I allowed, “but the ostensible purpose of the trip was Christmas shopping, which we did for the entire family. Especially for Mummy.”

The arrival of a waiter reminded my father of those chilled martinis, and we both ordered one. “You remember, of course, that I was sober for the last five years,” he said. “But now it doesn’t matter.”

“Amazing,” I said.

“You did like to buy things out of the window,” I said. “There was a store in Orbetello, near Rome, that had a dollhouse full of pet mice set up in the window, and you bought it on the spot.”

The drinks came, and he sipped carefully from the lip of his glass.

“That’s right,” he said. “I must have offered what seemed like a lot of money, and the man who owned the shop had to shake the thing violently to get the last female mouse out. ‘La donna,’ he explained.”

My father was never one of those tiresome alphas who couldn’t be teased, but when he took another pull on his drink, I could smell the tobacco smoke that had for decades accompanied the astringent taste of gin. He settled in his chair with a confidence since lost to literate American males.

“The state of the nation?” he asked, and I reached wildly for my own martini. I drank deeply, ate all three olives, and put the toothpick in the saucer for my teacup.

“If only you’d wanted to meet me for lunch during the Obama era,” I said.

Of course, he’d think I invented the Trump presidency as an excuse to feel sorry for myself. I considered lying.

I had lied to him, when I banged up the Studebaker. That false-hood was never discovered since his station wagon had had so many previous collisions that not even his guilt-ridden son could tell in the cold light of morning which one had occurred the night before. I don’t remember much at all about that night, except that I was with a girl, a pretty girl, who had blue jeans with a busted zipper.

She couldn’t close her pants, which turned out not to be a good sign, although we liked each other as friends and all.

That next morning, I told him about the zipper, but not about the ding on his car. Now I was tempted to lie again.

“Let’s order first,” I said, since the waiter was back at our table, this time with a pad and pen.

“Well, that much is easy,” he said. “If we get the family dinner for two, we can have wonton soup, egg rolls, the barbecued spare ribs, and pay extra for the lobster Cantonese.”

Both the waiter and I nodded in mute agreement. “So, state of the nation?” he asked again.

“Donald Trump gets into an elevator and a gorgeous model gets in with him?” I said. “Have you heard it?”

“If I heard the joke, I’ve forgotten,” he said.

“When the elevator doors close, she puts his hand on her left breast. ‘We’ve got a minute,’ she tells the Donald. ‘Can I please, please give you a blow job?’”

Just then, the soup and egg rolls arrived, and my father reached out, touched one of the egg rolls. “Ouch! Hot!” he said, and pulled his hand away.

“Wrap it in a napkin,” I said, but he’d already speared the offending appetizer with a fork, moved it to his plate, and was cutting off a piece.

“Back to the joke,” I said. “So, the model asks Trump what he’s waiting for. ‘I’m trying to figure out what’s in it for me,’ he said.”

This got a smile, but not a laugh. “I don’t know why you’re talking about Donald Trump. I wasn’t all that interested in him when I was alive. I’m going to the restroom,” Daddy told me, “and if you encounter the waiter, order another martini for me.”

I nodded and was delighted to see that when he stood and walked, he wasn’t favoring his right leg, the one that had been riddled with cancer.

“I don’t know what Donald Trump has to do with anything,” he said, when he got back. “I am curious though about the state of the republic.”

“Let’s start in with idle chatter,” I said. “Why does an all-powerful God allow suffering?”

“There are dozens of excellent books on the subject, most of which—I daresay—you haven’t bothered to read,” he said. “I don’t want to spend our only lunch together in 25 years mulling over the problem of pain,” he added, cutting into the noodle in his soup with the side of a large, stainless-steel spoon. Then he brought the steaming wonton to his mouth, blew across the surface, and swallowed.

I held my peace.

“You’re not going to ask me for money again,” he said, and took a pull on his martini.

Again, I said nothing. “There’s no cash in heaven.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I heard. You can’t take it with you.”

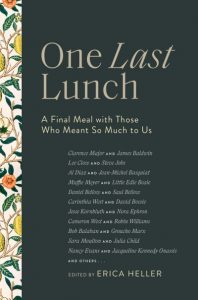

“Well, if you’re not broke, why did you arrange this lunch?” he asked. “Don’t tell me it’s for that book that Heller girl is putting together.”

“Erica’s her name,” I said, “and that’s certainly the genesis of this lunch, but that’s not why I set it up.”

“Okay,” he said, and used a knife to separate out one of the barbecued spare ribs. This he dipped in hot mustard and took a bite. His eyes filled with tears. He took three long pulls on his water glass, then another slug of gin.

“Are the ribs as good as they used to be?” I asked.

Daddy nodded, took another bite, put down the rib, and wiped his lips with an impossibly thick white napkin. “Heavenly,” he said.

“What’s it like in heaven?” I asked.

“What leads you to conclude that I’m in heaven?” he asked.

“I just assumed,” I said. “You wrote like an angel. No burn scars.” “Do you honestly suppose that people coming up from hell all look charred, as if they’d been hamburgers taken off the grill too late?” he asked. “And do I catch disappointment in your voice? Were you picturing your poor old father dancing around on a bed of charcoal briquettes, while horse-faced creatures with cloven hoofs lashed at him with bullwhips?”

“Not disappointed,” I said. “Nor surprised. I’m delighted. I loved you. Love you. And by the way, you look great,” I told him, as I finished slurping my soup.

“That’s the thing about the dead,” he said. “We always look the way people remember us.”

“I hadn’t thought it through,” I said, “but you do look a lot like the way I remembered you, only somehow filled in, more corporeal than when alive. And of course, you’re in a suit. At home you were in a crewneck sweater, often torn at one elbow. And wash pants. Remember the ones they sold at the Army Navy store with the patented grow feature, which was a nip they’d taken at the waist, a nip that you could let out?”

“Yeah,” he said, “the only way you could grow was fat.”

“Maybe it’s the gin, but you seem to have a glow about you,” I said.

“I’m down from heaven, for Christ’s sake,” he said. “Of course I’m numinous. I’m not in hell, though I can’t exactly thank you for that. I mean, the stories you detailed in therapy—”

“That’s therapy,” I cut in. “You’re not supposed to be fair in therapy.”

“Nor accurate either?” he asked.

“As a master of fiction,” I said, and this made him blanche. “As a master of fiction,” I said, enjoying the fact that the second reference also made him blush. “John Cheever of all people should understand that accuracy is something we search for, not a series of facts that have been established.” I took a rib.

He remained silent while I chewed and swallowed. “I’m still not a homosexual,” I said. “If that’s what you’re worried about.”

“I’m no longer worried about that,” he said. “That was what they call a projection of me onto you.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Just as my yearning to be a great writer was a projection of me onto you.”

My father began to crane his neck, apparently looking for a waiter.

“I’ve missed you,” I said.

Silence.

“Of course, I’m pleased,” he said, “though not entirely convinced.”

“Sure, I miss you,” I said. “Remember you’d be in your armchair when I came back home at night from a date, and you’d ask if you were a disappointment as a father?”

He nodded. “I was sometimes a chore.”

“Sometimes,” I agreed, “but I was also flattered. And you’d say that you weren’t like an ordinary father, and I’d say that I didn’t mind, because ordinary fathers were crashing bores.”

“You said that you sometimes experienced a species of loneliness so intense that it felt like intestinal flu. This was during one of the most successful phases of your career.”

He smiled, though weakly. “You were always adept when it came to saying what was wanted.”

“I mean it,” I said. “I understand you, because I’m lonely, too. You remember when you took me and my first wife, Lynne, to London, and gave her 50 pounds to go shopping, so that you and I could be alone together?”

He looked vague. “Remind me.”

“You and I walked around the Serpentine in Hyde Park. You weren’t drinking, but you encouraged me to have some silly drink. A plimsole?”

“You mean a shandy,” he said.

“That’s right,” I said. “A shandy. And then you said that you sometimes experienced a species of loneliness so intense that it felt like intestinal flu. This was during one of the most successful phases of your career. And I thought how odd it was that a man so much admired could be so lonely.”

He was peering around now and seemed to have stopped listening.

“I didn’t know the kind of loneliness you were talking about then,” I said, “but I do now. I often feel that lonely myself.”

He cleared his throat. “I’m sorry to hear that,” he said, but he didn’t look at all sorry.

“Your writing has kept other people from being lonely. I’ve met women who saw you speak forty years ago and are still vibrating. They were in the back of the auditorium and you were at the podium. You said that good prose could cure a sinus headache or athlete’s foot, and the woman in question would never afterward have a single doubt about her life or work. I only wish you’d given me that sort of encouragement.”

He smiled vaguely. “Did I say that about athlete’s foot?”

“I’m not sure,” I said. “You can look it up in the biography.”

“I haven’t read it,” he said.

“It’s a masterpiece,” I said.

“I’m glad,” he said. “I’ll take your word for it.”

Our waiter appeared, took our order for more martinis, and another man came to the table with a chafing dish. He took off the cover and gave us each some lobster Cantonese. Daddy insisted I take the big claw. The waiter looked at us for some sign of approval, and we both nodded and watched politely, while he put the scoops of white rice on our plates.

We both leaned forward and ate in silence for a time. “So, what’s the problem?” he asked.

I gulped down some more martini, cleared my throat, and began: “We have an orangutan in the White House. Trump! People are afraid the world is going to end,” I said. “There’s a lot of talk about the Rapture, which alarms me.”

“What’s the matter with Benjamin Hale?” he said.

“He cries enough to fill a pail

“Oh, what’s the matter Benjamin Hale?

“He cries enough to float a whale.”

I sensed that our time was almost up and signaled to the waiter, who brought the chit, and I asserted the authority of the living by putting my platinum American Express card in the fake-leather pocket designed to receive it.

“I remember that poem,” I said. “But you have to believe me when I tell you that there’s lots of trouble down here. People more naturally cheerful than I am are losing sleep.”

The waiter came back, and I added the 20 percent tip, signed, and put my card back in my wallet.

“I don’t know if this will shed any light,” he said, “but they’ve closed purgatory. Freed up a lot of space, which we are in need of, especially if they decide dogs have souls. It’s going to be so crowded, nobody will be able to lie down.”

“But why don’t you need purgatory anymore? Wasn’t that mostly a Catholic thing?”

“It was,” he said. “But they found that the time spent watching the TV news was painful enough, and in just the right way. They found that when they came up with a soul that owed time in purgatory, he or she had already suffered eons in front of the screen.”

“Interesting,” I said.

“So that’s my answer,” he said. “If you think the world is going to end, then turn off the television.”

“So, I should tell my friends that if they turn off the TV, the world won’t end?”

He pulled out his chair, stood, and grinned. “The world might end. I don’t know. I went to heaven, not to Delphi. What I do know, though, is that if you turn off the TV, you’ll have a better time until it does end. Which is enough, don’t you think?”

“I guess,” I said.

By now, we were standing in the street, about to part.

He shrugged and beamed. “We should do this again soon,” he said. “I’ve really missed the lobster Cantonese.”

__________________________________

One Last Lunch: A Final Meal With Those Who Meant So Much To Us edited by Erica Heller . Copyright © 2020 by Erica Heller. Excerpted with permission by Abrams Press.

Benjamin Cheever

Benjamin Cheever has written for the New York Times, The New Yorker, and Runner’s World. He illustrated craven moral flexibility well before it was in vogue by contributing to the Reader’s Digest and the Nation within the same five-year period. He’s published four novels and three nonfiction books. He has taught at Bennington College and the New School for Social Research, and lives in Pleasantville, New York.