Imagining a Black, Queer Aboriginal Melbourne

On the Urban Design and Activism of Lisa Bellear

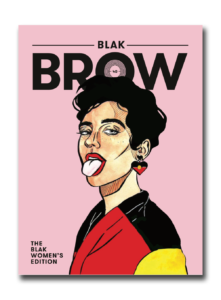

This essay originally appears in issue 40 of The Lifted Brow, a special edition “created entirely and independently by a First Nations collective of editors, curators, academics, designers, and activists.”

![]()

1.

Concrete and dislocation. I can’t dream in Naarm, even when Koori mob share culture.

I was studying urban planning, a peculiar contradiction, trying to assert myself in a degree where Aboriginals didn’t exist. Trying to understand what right or role I played as a Ballardong Noongar woman contributing to thought and discussion on Koori land? But Lisa was Dreaming in Urban Areas, a Goernpil (Stradbroke Island) woman who found community and purpose in Naarm. She’d lived and dreamed along northern streets while my lecturers consigned Aboriginal content to remote Indigenous housing in the NT. Because there were no mob down south who needed a place to sleep.

Image by Timmah Ball

Image by Timmah Ball

Slowly I found Tiddas like Yuin architect Linda Kennedy, and we thought about our role as black people working in the built environment, when the built environment was a white thing.

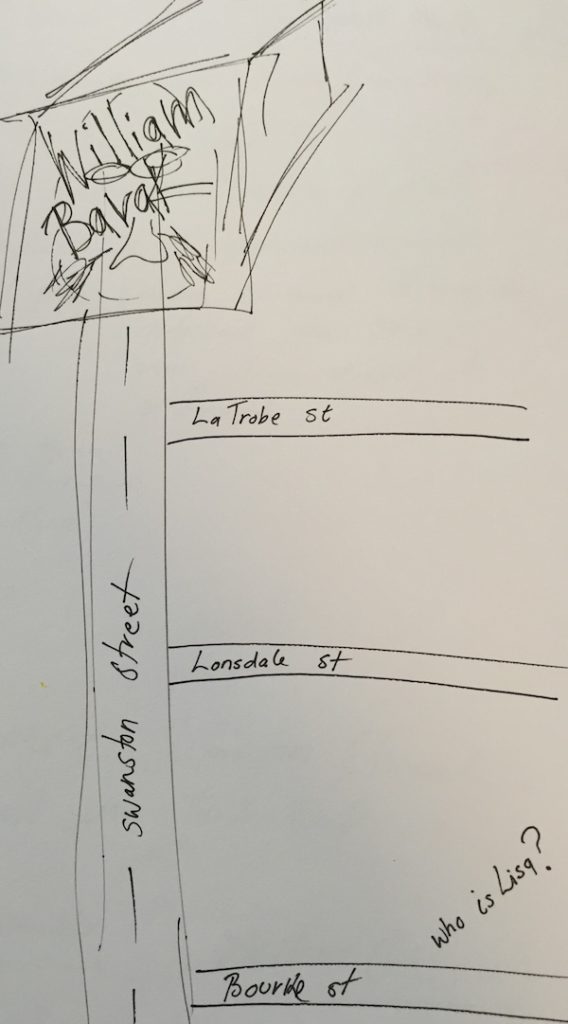

We imagined new ways of dreaming in cities, beyond the sudden interest in black design. As if black design meant slapping a picture of a black man on the face of a building without interrogating what this means. Whose land we walk on, who William Barak was and continues be. And how the building would or could ever have meaning to mob. Beyond seeing a black activist conspicuously gaze down Swanston Street.

2.

When you google Dreaming in Urban Areas a link to Amazon.com comes up. When you click on the link it says this book is not available. It’s rated 4.65 on Goodreads and described as “anything but motionless.”

David Unaipon award-winner Jeanne Leanne asks that we remember and re-read our black authors, even as they disappear from mainstream culture. Black mob remember Lisa but whites often think remembering is a plaque or a statue.

Photo by Tom Ross.

Photo by Tom Ross.

3.

In 2017 I meet Kim Kruger at the “VU Place Politics and Privilege” conference.

It’s intimidating presenting in the small lecture theater filled with women like KJ, Paola and Kim. Later we amble around long tables ornamented with sandwiches and orange juice talking about exploitation, appropriation and rapidly changing Fitzroy. Kim immediately connected with my criticism of gentrification and tokenistic black design.

We started talking about Lisa and Kim mentioned that her image was used in an architectural marketing campaign for luxury housing we’ll never afford. No one asked for consent to use it. I imagine Lisa laughing at her sudden cultural cred, laughing at the peculiar irony of a black activist becoming a draw card amongst the swimming pool, gold-plated interiors and other symbols of latent capitalism which saturate the website. A week later Kim emails me a screen shot as if to confirm my own suspicions that the popularity of black culture is not something we will necessarily, if ever, benefit from.

5.

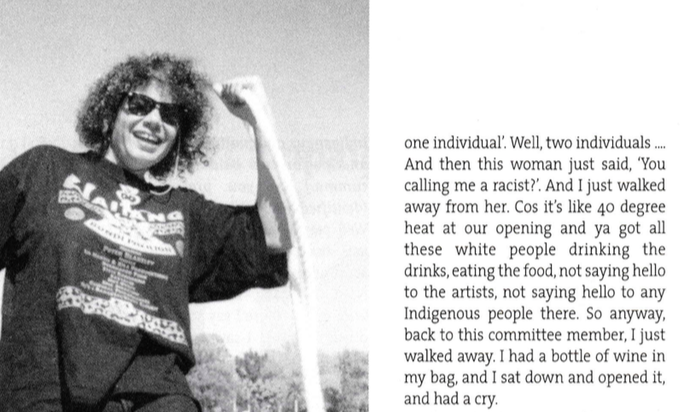

Lian Low interviewed Lisa for a paper called Lesbian Network in 2001 and sent me a copy of the article. Talking to people like Lian and Kim introduced me to her work in new ways. Activism was equally as important as writing.

I read the interview and read Lisa’s poetry repetitively. Imagining what Naarm would have been like in the 1990s and early 2000s as a queer black woman. Imagining Lisa working excessively for community, organizing protests, photographing events, writing, researching, learning, nurturing.

Lisa was on the intersection before it existed, before intersectional feminism exploded and was co-opted by the white women it promised to critique. In the article Lisa chose to be black before queer because there isn’t any other possibility. And the queer community at the time erased Indigenous identities. And she was tired and fed up. Lian didn’t edit out the number of times she swore in the interview, unimpressed with her involvement in Misdsumma.

A lot has changed and hasn’t. Naarm bursts with black queers who wear their identities with electric pleasure. But there are occasions where we circle on the edges our voices dimensioned within gaystream rhetoric. Where the problems of white cis middle-class queers occupy space on land they will never acknowledge does not belong to them. We sit silently, aware of our ancestors, aware that things are better for us younger mob, because of Lisa’s exhaustion. Things have improved because of the time Lisa swore in Lesbian Network magazine, when the only thing she could do was swear without being censored.

6.

I quote Lisa in a longform literary essay for an anthology. It’s my first notable publication and I’m invited to a writers festival. I’m starting to feel that I’m edging closer towards being a writer. But the initial editorial feedback on the essay burns. I’m told to remove Lisa, the readers won’t know her, it confuses the argument, and isn’t necessary. But I need Lisa. She articulates the humiliation I feel when it slowly unravels that my identity has been tokenized for the benefit of a white woman’s career. As Lisa says in her poem “Feelings”:

sometimes you just have to walk away,

laugh at their ignorance

and preserve your own dignity

And her words remind me that walking away is not always the easy option, sometimes it’s the only option. So I start to walk away from hostility and white fear, without feeling guilty that I didn’t stay for the fight.

Image by Miff Costigan. Courtesy of the 2001 issue of Lesbian Network.

Image by Miff Costigan. Courtesy of the 2001 issue of Lesbian Network.

7.

“Dreaming in Urban Areas” was the title of a photo of Lisa taken by Destiny Deacon in 1993. In the image Lisa looks like she’s anointed in tribal body paint, but she is actually just wearing a Blackmore’s facial scrub.

8.

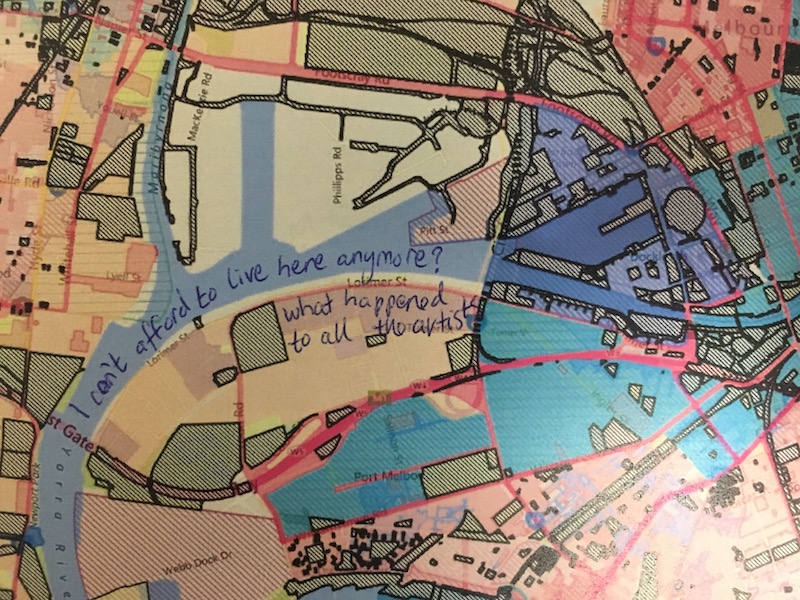

The young white male writer slumps in his chair at the Arts House Supper Club, bored and a little annoyed. We’ve met a few times now and my Aboriginality either mystifies him or is considered an interesting nuance I can bring to a range of environmental projects. On this occasion he seems a little pissed off, eyes rolling when I talk about white voices dominating the housing affordability debate. I read Lisa’s “Beautiful Yuroke Red River Gum” and the other white academic/expert on gentrification seems equally annoyed. Blacks have got bigger shit to deal with than reading literature reviews on how Melbourne could learn from Berlin to protect creative communities from rising house prices. And maybe it’s a little absurd complaining about being pushed out of the inner north when you’ve done a pretty good job of pushing us out of most things.

Image by Timmah Ball.

Image by Timmah Ball.

9.

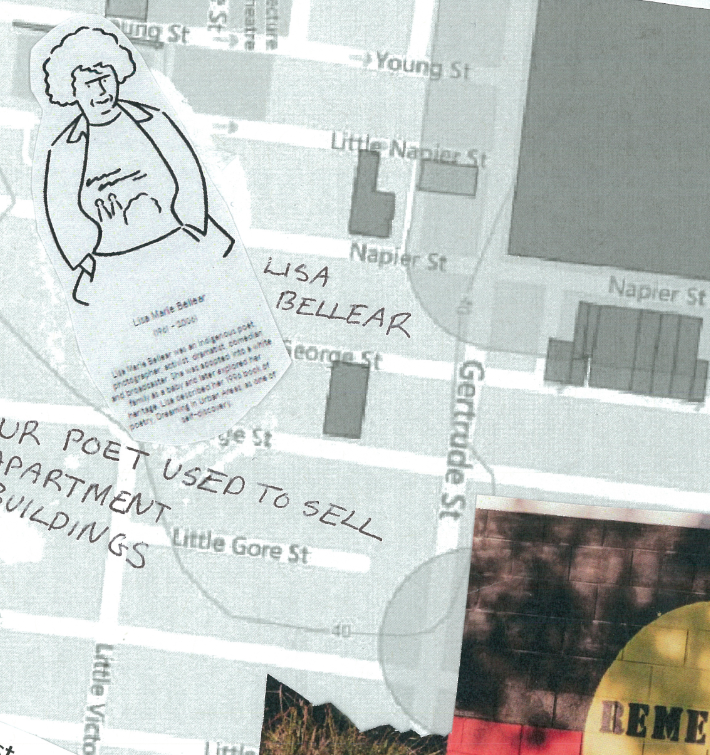

I’m commissioned by Māori urban design academic Dr. Rebecca Kiddle to contribute to the book Our Voices. It aims to advance the field of architecture by offering multiple Indigenous perspectives on design theory and practice. Indigenous authors from Aotearoa NZ, Canada, Australia, and the USA explore the making and keeping of places and spaces informed by our values and identities. I’m honored and tired by the circular nature of theory.

Another essay, conference, symposium, and opening. Or a new building with Indigenous design on the facade. I think about Lisa on the website advertising boutique apartments in Collingwood and wonder if this is Indigenous architecture. I submit a collage to the book because I can’t write about the subject anymore.

Image by Timmah Ball.

Image by Timmah Ball.

10.

Architects are quick to stake a claim in black design. But some additions to the built environment honor her legacy respectfully. The City of Melbourne names a lane in her honor and Kim worked with planning to find the right title.

11.

I walk through ACCA weighted by anxiety and self-doubt. Paola Balla’s exhibition “Sovereignty” draws us through the doors of the building with sharp asymmetrical angles. I hadn’t been to the gallery since undergrad art history where post-modern minimalism from international artists gilded the large space with rhythmic uniformity. Other students were impressed but it left me cold, or maybe I just didn’t get it? I got shit marks and they got jobs in the arts industry.

But this was “Sovereignty” and Lisa’s photos were on the wall. Down the road, “Close to You: The Lisa Bellear Picture Show” is on at KHT and co-curated by Kim. My friends bought me the catalogue like they somehow knew I needed it. I read it on the train on the way home, enamored by Celeste Liddle’s words and other essays on Lisa throughout the book. And I start to realign my own worries, understanding the women who came before me and what they had given.

12.

A new Lisa Bellear book comes out called Aboriginal Country. It’s always strange when a book is released posthumously, and we’re left wondering what the author would say about it if they were able to speak to it. But it also creates an ongoing legacy, although her words live in multiple ways.

13.

My tidda calls me because they can’t find their copy of Dreaming in Urban Areas. I tell them I’ve got it and they ask for it back. I tell them I’m keeping it safe, nestled next to her new book Aboriginal Country.

But I understand their need to know where it is, to never lose it. Writing like theirs thrives because of Lisa’s words. Their books exist because of Lisa’s work. Books imbued with light and generosity against the discord of colonialism.

And like Lisa caring for community carries more weight then their own practice of writing, uncompromisingly dedicated to supporting others. So I understand why they need to keep it close. We dip into her pages, retracing her words, to understand who we are. Her book leaves my shelf and travels to their home. Always imagining Lisa dreaming in urban areas.

__________________________________

From The Lifted Brow #40: The Black Brow Issue. Used with the permission of The Lifted Brow. Copyright © 2018 by Timmah Ball.

Timmah Ball

Timmah Ball is a writer and urban researcher of Ballardong Noongar descent. She has written for The Griffith Review, Right Now, Meanjin, Overland, Westerly, Art Guide Australia, Assemble Papers, The Big Issue, The Lifted Brow, the Victorian Writer magazine and won the Westerly Patricia Hackett Prize for writing.