Ilan Stavans on Sympathy, Eroticism, and the Practice of Revision in Translation

The Author of Selected Translations In Conversation with Peter Cole

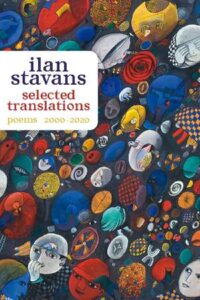

What does it take to translate a poem from one language to another? In what sense is the translation an altogether new poem? How does one reach the right tone, the right rhythm, the right version? And is there a “right” when it comes to translation? Ilan Stavans and Peter Cole explore these and other questions in this exchange, which took place electronically in February 2021, on the occasion of the publication of Stavans’s latest book, Selected Translations: Poems 2000-2020, just released by University of Pittsburgh Press. It features translations into English of poetry originally written in a dozen languages, including Spanish, French, Ladino, Yiddish, Hebrew, French, and Portuguese, by authors such as Neruda, Yehuda Halevi, Sor Juana, Isaac Berliner, Federico García Lorca, Ferreira Gullar, and Juan Gelman. Stavans is the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College and the publisher of Restless Books. MacArthur-winning poet and translator Peter Cole’s most recent book is Hymns & Qualms: New and Selected Poems and Translations (2017). His new collection, Draw Me After, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

*

Peter Cole: This new gathering of your translations contains a remarkably wide range of poets, from multiple languages and distant worlds, known and less-known. How does a given poem get into your blood? Where does a translation begin for you?

Ilan Stavans: I start by finding out if I feel empathy toward a poet and if I indeed might be able to recreate the rhythm of her original work. That’s my principal objective. I’m never literal in my translations though I’m always truthful. I disagree with the view that a translation is like a lover: if it’s loyal, it can’t be beautiful and vice versa. I strive for beauty, even if beauty is a strange concoction that can’t be magically summoned; it happens if the right ingredients are in place. Looking back, I realize it is the poem that chased me, waiting until I paid attention to it, making time for us to get to know each other.

PC: Exactly, in the beginning is rhythm. Texture. Tension. So many arguments over translation zero in almost exclusively on le mot juste, which of course matters a great deal: but that isn’t where good translations come from. They come from a much more physical sort of encounter with the language of a poem or piece of prose—and with a feeling for its shape and movement through us. Empathy is one way of putting it, and a complex experience of beauty certainly enters into play in a major way. At least at the start, I tend to see it more as a matter of sympathy—in the way that physics or music uses the term in relation to the vibration of adjacent surfaces. The erotics of translation is much undervalued! Richard Zenith has a marvelous essay about that, where he talks about the “risk-taking attitude crucial for getting close to the text, in the same way two people get close.”

IS: “Erotics” is the right word, since what I engage in is a sensuous relationship with the poem. When I translate—and not only poetry—I feel as if I’m in another dimension. In part this is because rather than originating the text from scratch, as I do when I’m writing a piece, say an essay or a story, as a translator I’m following someone else’s lead, which means I trigger a more reflexive part of my language. Through translation, I redress a poem. Its body is the same in the original and in my version; only the presentation is different.

PC: “Redress” is an interesting way to put it, since it also suggests righting a wrong, coming up with a remedy or compensation. That seems to apply to the situation of translation, no?

IS: I like the associations you’re making. A poem in translation remedies its isolation in the language into which it came into the world. But it does more: it recalibrates the poem, making it a fresh creation and bringing it into other horizons, so both worlds are changed—where the poem came from and where it’s going.

PC: Let’s get back to slightly brassier tacks. The poem has caught your attention. You’re inside it and it’s in you. Where does revision come into this dance?

I disagree with the view that a translation is like a lover: if it’s loyal, it can’t be beautiful and vice versa.

IS: All writing is rewriting. The first draft is like making a sketch on a piece of white paper. Once the sketch is done, I know what I’m creating. But that is only the first approach. I will return a half dozen times, maybe more, before I begin to be satisfied with what I’ve written. Each time I’m able to see more clearly what I’m striving for. A finished piece is 10 percent writing and 90 percent rewriting. The same process takes place with translation. A translation of mine goes through countless versions. Often after it has been published I still see it as a work-in-progress. I must have four or five versions I’ve done of José Martí’s “Dos patrias” in circulation, all titled “Two Homelands.” The best one, in my opinion, is the one I’m yet to do.

PC: Well, that comes to Ten Homelands, but we all know the feeling, about so-called original work too— as Beckett and scores of illustrious others have made painfully and refreshingly clear. (“Fail again, fail better …”, etc.) With translation the situation is somehow exacerbated by all the clichés about compromise that flutter around works like tiny white flags of surrender. The translator’s halo. How do you deal with the frustration of sensing that what’s “out there” isn’t finished?

IS: My way may be solipsistic: I ignore that a piece is in the world already; or worse, I tell myself the real world is only a dream and that a better version will inhabit another dream.

PC: Where does that leave the reader?

IS: In the same position I’m left when reading others in this Leibnitzian reality: we’re all drafts—a declaration of love is a draft, a grocery list. What we read as readers are versions, just as we readers are versions of ourselves.

PC: Beautiful—a high-resolution imperfection, in all senses of the imperfect, and translation as a paradigm of receptivity and vital movement. That said, I do believe—and feel that I have to believe—that I’m working toward a, or even the,ping-perfect translation of what I’m translating. One could call that a false proposition, but it might be more accurate to say that it takes us into the realm of fiction, and that I’m translating my experience of a given work, not the work itself in some pure or objective sense. We each have our methods of tricking the translation out of ourselves. In the preface to this new book you explicitly say that you see translation as something akin to “immigration,” and “approach translation as hallucination.” “Liberation” is also in that mix for you. Are they related?

IS: For me translation is intricately linked to my immigrant life, mine and that of my ancestors and successors. I come from a line of Yiddish-speaking Jews from the “Pale of Settlement.” I can’t trace their lineage more than two or three generations, though it is likely others before them migrated too. My family, in other words, never had a permanent address. The fact that I was born into Spanish was an accident of history. Translation is a mechanism of survival: you learn as many languages as possible in order to cope with the circumstances. In my case, I’ve turned that mechanism into a craft—a means of becoming in a new landscape.

As for hallucination, let me tell you a brief anecdote. A few years ago, I participated in a shamanic ceremony in the Colombian Amazon in which I ingested Ayahuasca, an ancient hallucinogenic. The ceremony lasted several days but it seemed closer to a week, maybe a month. I experienced the texture of things through a different lens. And words—they were like knives. Somehow I felt as if I had reached the meaning of things in a way I didn’t know existed. The closest I’ve ever come to what happened to me there is in my daily life as a translator. Because when I translate, I’m at the mercy of words: their edge, their weight, their power; I am also in another dimension. My intellect is at work but so are other ways of knowing that are experiential rather than rational.

All writing is rewriting. The first draft is like making a sketch on a piece of white paper.

PC: In short, trance-lation! And where is liberation here? Most people think of translation as The Great Constraint.

IS: Liberty isn’t the capacity to do whatever one wants but to do what one wants within the constraints set by the political, economic, social, and cultural eco-systems in which we live. Translation is a ripe example of that: freedom is plentiful within the parameters offered to us by the original poem. A translator will always be aware of limitation, but when I translate I sense the joyfulness of liberation. By the way, I would say the same of any work of the imagination: as artists we can’t imagine anything we want; we can only imagine that which is framed by the possibilities of our circumstance.

PC: A slightly random question, but perhaps a good place to end: One of my favorite poems in this book is your version of Neruda’s “Ode to a Dictionary”—“From the dense and sonorous / depths of your jungle, / give me, /when I need it, / a single birdsong,…” It’s a poem about the poet’s discovery of all the Spanish dictionary contains and what he’d missed before he came to that realization. Do you think it’s also about translation?

IL: It’s one of my favorite poems by Neruda. Sometimes, as I prepare myself to translate a new poem with the dictionary at my side, I think that my version is already in its pages; my job is simply to unscramble the words, to arrange them in the right way. Neruda says that when he was young he looked down at dictionaries as tombs but in adulthood he came to understand their value: They’re “hidden fire.” This poem is one of the most moving tributes to what Neruda calls “the granary of language.” And that’s where poetry and translation meet.

__________________________________

Selected Translations: 2000-2020 by Ilan Stavans is available now via University of Pittsburgh Press.

Peter Cole

Peter Cole was born in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1957. His most recent book of poems is Draw Me After, and he has also translated widely from Hebrew and Arabic works—both medieval and modern. He is the recipient of many honors, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature, the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, a National Jewish Book Award, and a MacArthur Fellowship. He divides his time between Jerusalem and New Haven.