Ijeoma Oluo on the Pervasive Impact of White Mediocrity

Jasmine J. Mahmoud Talks to the Author of Mediocre

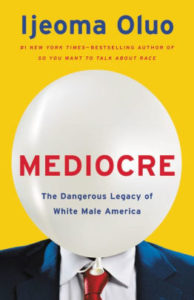

In 2015, Black Canadian writer Sarah Hagi tweeted: “Lord, give me the confidence of a mediocre white man.” The sentence “launched a thousand memes, T-shirts, and coffee mugs,” author Ijeoma Oluo writes in her newest book, Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America. She continues, “[t]he sentence struck a chord with so many of us because while we seemed to have to be better than everyone else to just get by, white men seemed to be encouraged in—and rewarded for—their mediocrity.”

Five years after that tweet and within the debut year of Mediocre, I caught up with Oluo via Zoom in late December 2020. Mediocre traces structural and cultural histories of how white men have been conditioned to expect to (artificially) feel superior, a dynamic that perpetuates mediocrity. Her argument is not—given the ubiquity of this phenomenon—that white men are inherently “mediocre.” Rather, Oluo suggests that “[w]hite male mediocrity harms us all” as it “requires forced limitations on the success of women and people of color in order to deliver on the promised white male supremacy.” Mediocre chronicles these histories thematically and across political movements, racist housing policies, higher education, the workplace, athletics, and the arts.

“You could write hundreds of books” on the topic, Oluo told me. Recognizing the vast ground she had to cover, in early 2018 she hired “two amazing research assistants” trained in social science and history. Together they examined questions about the way white male identity had changed throughout history; some queries included: “How did we define manhood in the 1950s? What were people saying about women in WWII?” The book’s methods also include Oluo’s quotidian observations as a Black woman writer trained in political science.

Reading Mediocre and its numerous, well-illuminated examples recalls Toni Morrison’s recurrent findings of “the way that Black people ignite critical moments of discovery … in literature not written for them,” in her 1992 book Playing in the Dark. (Morrison also writes: “I had started, casually like a game, keeping a file of such instances.”) There are other resonances with foundational work by Morrison, Saidiya Hartman (who despite historical methods is housed in an English department), and Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the phrase “intersectionality.”

“Without [Crenshaw], without work of people like Angela Davis, I would be still muddling through it. A lot of what Dr. Crenshaw did [was to name] what that mechanism is, and what I’m trying to do is name another problem that’s related to it,” Oluo said. Her style in Mediocre mixes personal vignettes with highly sourced histories, and validates minoritized points of view. In our conversation, Oluo emphasizes that she “wants other people of color, especially Black people, to recognize” how their “stories belong here.”

In our conversation, I asked Oluo to talk more about the link between intersectionality and white male mediocrity: “What causes lack of intersectionality in the United States is people banking on their proximity to white male power,” she told me, invoking “white women thinking of their proximity to white men and how much power they can get collectively. But it’s also built on the ways in which we erase experiences further away from the white male experience. So what we see in white supremacy is, of course, not only an incredible lack of intersectionality, but [also] the motivation for denying intersectional experiences.”

At one moment while reading Mediocre, I experienced an intense “aha!”, remembering something my mother frequently says to me (echoing many Black mothers): “You are Black and a woman, so you have to work three times as hard.” Implicit in Oluo’s thesis about systemized white male mediocrity is an identitarian reverse (of sorts)—the immense weight put on Black women to uphold our nation’s best dreams, even as society still decenters and degrades them, including the widely-cited example of Black women’s voting practices and work by Stacey Abrams alongside many other Black women in Georgia. “Listen to Black Women,” Oluo writes in another moment in Mediocre, as a reminder and corrective.

We can also think pointedly of Oluo’s relief work in Seattle. Last March, Oluo decided to launch the Seattle Artist Relief Fund at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic’s tear. Alongside collaborators Ebony Arunga and Gabriel Teodros, Oluo’s efforts raised over $1 million, which was distributed to over 2,000 artists. One recipient told Oluo that the funding meant “not hav[ing] to move out of Seattle. So that has meant the world to me,” she said.

“To be able to give back to the community that sustains us… As someone who grew up in systems, who a few years ago wouldn’t have been able to financially survive this pandemic, I wanted to create something that had dignity. I feel like we did that. We showed you can trust people. People don’t have to spend three days filling out forms. They can just say, ‘I have to get some groceries.’ It was beautiful to see how hundreds of people across the Pacific Northwest wanted to support it.”

Now, Oluo points out that the aid from their effort is all that some families received. “What’s been heartbreaking was this was supposed to be a few weeks until whatever systemic approach kicked in and it never kicked in,” Oluo told me. “When people get money even this late in the year, they’re saying ‘you’re the only people who sent us anything.’ But it’s the story across this whole country. They’re absolutely willing to let entire populations just disappear, entire neighborhoods disappear.”

In the richest nation in the world, the lack of a cohesive COVID-19 relief effort reveals another mediocrity, where Black women-led efforts often distributed more money than our government.

*

A yet unnamed elephant: Mediocre’s argument deeply captures Donald Trump. “Yes, Trump’s multiple bankruptcies and business fiascos are good examples,” Oluo writes at one point. The book also skillfully reveals the tactics that uphold white male mediocrity and its forced position of superiority, such as how Trump’s policies, tweets, and speeches sought to demonize women, people of color, higher education, and football players protesting for racial justice.

Our interview took place weeks before the attempted coup by Trump supporters on Jan. 6, 2021. In Mediocre, her writing anticipates that event. “It is a reminder to refuse to let our shock and outrage distract us into thinking that these incidents do not all stem from the same root source, which must be dismantled. That source is white male supremacy,” Oluo writes. She continues, later, about social movements: “The Trump administration and its supporters want the removal of rights and privileges of women and people of color, and they want vengeance against women and people of color for the rights that they view were gained at white male expense.”

After the Wall Street Journal published a sexist op-ed that unnecessarily ridiculed Dr. Jill Biden’s credentials, a number of people tweeted out references to Mediocre to condemn op-ed author Joseph Epstein. “This dude has been writing horrific, racist, sexist, homophobic nonsense for decades and has faced no consequence. He’s the epitome of mediocrity,” Oluo said in our conversation. “But also I think it’s important to look at the context of how quickly people are willing to come and stand in defense of a white woman, and recommend my book, that’s also really highly critical of academia itself.”

Her chapter on higher education permeates with nuance. Higher ed, Oluo asserts, has provided minoritized populations greater access to higher income and career opportunities; however, she writes, “white male supremacy has been woven through the entire fabric of higher education.” In that chapter, she details Woodrow Wilson’s tenure as President of Princeton University, where he barred Black students from entry and fired Black employees; later as a US president, he would endorse segregationist policies. Early 20th century Harvard president Lawrence Lowell mobilized antisemitic and racist policies to starkly reduce the number of Jewish students and excluded Black students from living on campus and eating in dining halls. Oluo also details how, more recently, conservative political leaders – who benefited from higher education – have sought to defund academia through racist talking points; she offers a synthesis of those including “Obama went to college” and “Colleges are turning your children into ungrateful liberals who hate America.”

Oluo also draws from her undergrad experience as a political science major at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington, a 90-minute drive north of Seattle. “My political science degree … taught me valuable things about how our systems of government work.” But in our conversation, Oluo detailed how noticing absences in the curriculum—attuned to race—also held tremendous value in her training. “I was, in almost every class, the only Black person to bring up racial aspects to things. It reminded me of another level of learning how these systems work that white students miss.” Oluo entered college later in life—“my son graduated from kindergarten the day before I got my bachelors”—and witnessed how many white male students engaged in politics as impersonal sport “that never touch[ed] the reality of the lives of people of color in this country.”

Our interview took place weeks before the attempted coup by Trump supporters on Jan. 6, 2021. In Mediocre, her writing anticipates that event.“When you’re living as a poor broke, single mom—I saw how entertaining it was and how little they actually cared about these questions that were so vital to how I lived and how other people of color lived,” she said.

*

I first met Oluo in the fall of 2019 at Seattle University, where I teach. Our campus had chosen So You Want to Talk About Race as a book that all incoming students read. (Oluo’s 2016 foundational tome continued as a bestseller in 2020, after George Floyd’s murder rocked our nation to more seriously consider the legacy and presence of racism). During her visit, I was moved by the questions she asked, including, “What might it mean to center our students of color in our teaching?” In Mediocre, Oluo describes how “At every college I went to—every single one—at least one teacher of color broke down in tears describing their struggle to advocate for their students of color in such a hostile environment.”

In our conversation, I asked Oluo if there was anything she wanted students, faculty, or administrators to know as they read and each her books.

She replied: “I wish the universities understood the promise of growth and self-discovery, learning how to connect with other people, find out who you are, how to build relationships, how to challenge systems—all of these things that anyone who loves academia holds up. If you’re not encouraging that for students of color and for women, you’re failing your students and there is nothing in the degree of value that will outweigh that, because all you’re doing that is teaching them how to be used by a system instead of how to shake systems and shake the world.”

In Mediocre, examples also abound of how racism and white male mediocrity pervades even the arts, from describing a racist comedian to looking at the first American film, Birth of a Nation. “If there’s a space that’s going to get us thinking about new possibilities, it’s going to be the arts,” also Oluo tells me centering the role of the arts, and the imagination it allows, in anti-oppressive work. “The people profiting off our art are white men. For me as a writer, I regularly think about the fact that the people I pay are the only Black people I personally know who make money off my books. We have to really reimagine not only what we produce, but how that system works.”

In Mediocre, there is hopeful space for imagining new ways of being that don’t uphold white male mediocrity and the oppressive systems that follow it. “We have to imagine a white manhood,” she writes in the conclusion, “not based upon the oppression of others. We have to value the empathy, kindness, and cooperation that white men, as human beings, are capable of. … We have to be honest about what white male supremacy has cost not only women, nonbinary people, and people of color—but also white men.” Perhaps after the chronic calamities of 2020, this book might allow space to better understand white male mediocrity across history, to make space to imagine and practice more kind, empathetic, and exceptional ways of being for everyone.

__________________________________

Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America by Ijeoma Oluo is available now via Seal Press.